Dagestan Risks Becoming a ‘Yugoslavia in the Caucasus’

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 34

By:

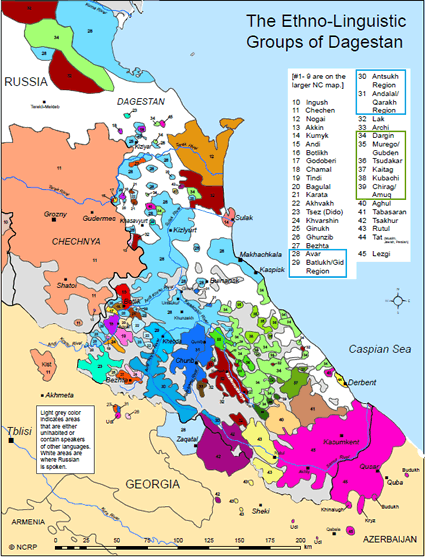

Dagestan, the most ethnically complex republic in the North Caucasus, faces an ever greater risk that it will disintegrate as Yugoslavia did. This growing danger exists both because of the changing demographics and power relationships within this Russian federal-level entity and due to the growing influence of Dagestan’s two neighboring regions—the country of Azerbaijan and the Russian republic of Chechnya—on its peoples. And as was the case with Yugoslavia, the disintegration of Dagestan would be not only bloody but would unsettle numerous relationships in the region and Eurasia as a whole.

In an article for Sevkavinform.ru, Musa Musayev writes that what makes the Yugoslav scenario thinkable in Dagestan are the rapidly worsening problems within the republic, most of which are longstanding, as well as the efforts of Baku and Grozny to expand their influence. The Dagestani neighbors’ moves on the republic certainly have precedents in the past, but are far more significant now given Dagestan’s own problems, Musayev notes (Sevkavinform.ru, February 20).

According to the journalist, the increasing influence of Azerbaijan and Chechnya reflects the fact that the two have much in common, even though one is an independent state and the other is a subject of the Russian Federation. Both have tightly-controlled power verticals, both have consolidated elites, and both are animated by a recognition of the need to overcome the results of destruction in a previous war, the first by the use of oil and the second by subsidies from Moscow. As a result, Musayev says, both have been able to mobilize their societies and boost the authority of those in power.

People in Dagestan can see all this, and it is in sharp contrast to what they see in their own republic, which remains mired in the past with ethnic groups and clans fighting among themselves for what money there is. Dagestan has oil like Azerbaijan, but it has not been able to develop it. And the money it receives from Moscow is not the basis for its economic development as it is in mono-ethnic Chechnya; rather, rubles from the Russian center have become “an apple of discord” and a source of corruption and internal power struggles.

In this situation, many groups within Dagestan believe that they could do better off if they lived in separate mono-ethnic republics rather than be roped together as they are now. The Azerbaijani and Chechen diasporas in the country promote that idea. In part, the former believe that the southern Dagestani city of Derbent is an Azerbaijani city (see EDM, January 26). And the latter think that Dagestan’s Khasavyurt and Novo-Lak districts, with their Chechen populations, should be handed over to the Republic of Chechnya. Musayev says local elites have already shifted their loyalties from Makhachkala to Baku or Grozny, respectively.

Exacerbating this situation are the calls by some Russian nationalists to do away with Dagestan and restore the tsarist-era administrative territory of Terek Gubernia, which would mean that the northern portion of the republic would be transferred to Stavropol krai. To make this palatable, these same nationalists have been promising some of the local non-Russian nationalists that they can set up their own national republics to the south. But there is no way to make any of these territories mono-ethnic without significant population transfers or, what would be even worse, a murderous campaign of ethnic cleansing.

Unfortunately, Musayev says, those pushing for the partition of Dagestan are thinking only about their own narrowly defined interests. At the same time, the current leadership of Dagestan does not seem capable of doing anything serious to resolve the internal conflicts or counter the moves of the Chechens or the Azerbaijanis. That only makes the effectiveness of the Azerbaijani and Chechen regimes more attractive to people in Dagestan and increases the likelihood of a Yugoslavia-type outcome there.

Besides inertia, only three things are keeping this outcome at bay, at least for the moment, although Musayev does not enumerate them. First, many in Dagestan are frightened by the assimilationist programs of Baku and Grozny. Generally, Dagestani ethnic groups do not want to give up their national identities and feel that they might be putting themselves even more at risk if they turned to either of these. Second, except for the four largest national groups in Dagestan, the nationalities there are so small that even their leaders do not believe they could make it on their own. Thus, they feel they are better off as small fish in a small pond rather than as small fish in a large ocean, which they fear they would flow into if the Dagestani republic were to break apart. And third, at least for the time being, and despite all its talk about the amalgamation of non-Russian areas with predominantly Russian ones, Moscow will oppose any such moves lest they trigger others, which would further call into question Russian control of the North Caucasus.

If Dagestan were to disintegrate in a Yugoslavia-type scenario, it would almost certainly trigger the splitting apart of the two bi-national republics in the region (Karachaevo-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria), demands for the formation of a unified Circassian republic, and challenges along the borders of every other republic in the region. Consequently, Moscow and Makhachkala are likely to do everything they can to maintain the status quo. But the fact that many are now questioning whether that is possible should be a wakeup call for everyone concerned about the region.