Energy Resources and the New Great Game in the Eastern Mediterranean

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 17 Issue: 137

By:

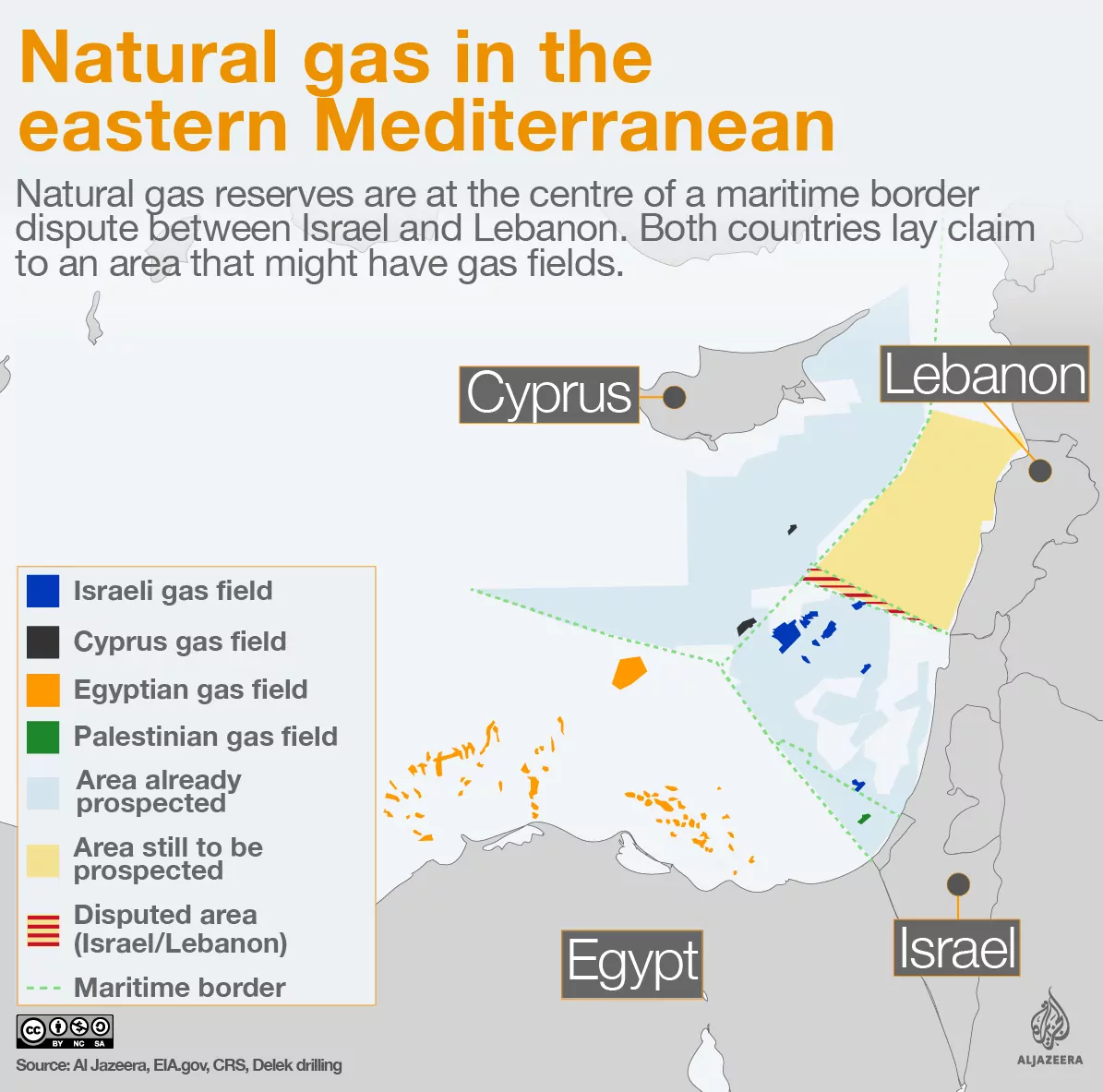

Control over energy resources and transit routes has long been a source of rivalry and competition among major powers with interests in the Middle East, Caspian Sea basin and Central Asia. And since the early 2000s, a new “great game” of sorts has embroiled local and outside players in competition over access to offshore hydrocarbon fields in the Eastern Mediterranean. Each of the region’s coastal states has declared an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), extending 200 nautical miles, to exploit energy resources on the seafloor—in certain cases leading to competing claims for the same offshore areas (TRT World, September 1).

According to a number of Turkish analysts, the strategic geopolitical importance of the Eastern Mediterranean is clearly illustrated by the fact that the European Union granted all of Cyprus (including the Turkish Cypriot territory not de facto controlled by Nicosia) membership without the divided island country fully meeting the bloc’s accession criteria requiring the resolution of all border disputes. Given the European Union’s heavy dependence on imports of foreign energy, the accession of Cyprus arguably allows the EU to assert legal control over a larger area of the energy-rich corner of the Mediterranean (Alternative Politics, October 2015; Sabah, July 13, 2019; Ankasam, August 30, 2019). Similarly from a geo-strategic perspective, neighboring Turkey considers Eastern Mediterranean energy resources as well as the country’s central position as a major littoral state to be key elements that will allow it to fulfill its plan to become a regional natural gas hub and transit corridor (Anaodolu Agency, July 22, September 3; Mfa.gov.tr, September 16).

Other major players in this area see Turkey’s regional intentions and are organizing to contest them. On September 22, the governments of Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Italy, Greece and Cyprus met in Cairo and formally established the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, aimed at increasing regional cooperation and joint efforts to exploit offshore gas. The formation of this forum was met with explicit opposition from Ankara. Some experts believe that the rising tensions between Turkey and its neighbors, coupled with the high costs associated with transit and infrastructure needed to bring these energy resources to market, are likely to seriously undermine the gas forum’s success (Dunya.com, September 26). Relatedly, the chronic tensions between Turkey and Greece in the Mediterranean are increasingly on the agendas of both the European Union (with Greece and Cyprus being members) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO—with Turkey and Greece both members) (Yeni Çağ Gazetesi, September 23)

Russia remains The EU’s single largest gas supplier and does not want to see its share of the European energy market reduced by Eastern Mediterranean fields coming online. And for this and other reasons, Moscow has also been stepping up its activities in the region over the past decade. Since entering the Syrian civil war to prop up Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Russia has been expanding a coastal logistics facility in Tartus into a full-scale naval base; and Russian military ships routinely operate in the Mediterranean Sea. Illustratively, in December 2019, the Russian Military-Maritime Fleet held joint exercises in the Mediterranean with naval vessels from Syria, whose government is politically and military backed by Moscow. Furthermore, in recent weeks, as tensions between Turkey and Greece escalated, Russia offered to help resolve the crisis in the region (Haberturk.com, August 14)

Meanwhile, France has been jockeying with fellow EU member Germany for a leadership role in resolving the tensions in the region (Tabnak.ir, May 27). The French fleet is based in the Mediterranean, and Paris is seeking to increase its influence and presence in the eastern portion of the sea, in part by offering to sell more weapons and warplanes to Greece and Cyprus. In late August, the presidents of France and Turkey, Emmanuel Macron and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, respectively, spoke by telephone as tensions escalated in the region (Hurriyet, August 26).

According to some observers in Ankara, developments in the Mediterranean are likely to enter a new phase following the November presidential election in the United States if the Democratic Party challenger, Joseph Biden, wins the presidency. Turkish analysts posit that a Biden administration may become significantly more active in the Eastern Mediterranean, and will likely cooperate more closely with Greece to contain Turkey (Daily Sabah, September 27).

As the situation continues to churn, Russia and France are working to boost their influence in the region at the expense of the US’s more passive policy. Meanwhile, China has chosen to monitor developments in the Eastern Mediterranean from afar. China’s energy security—unlike the European Union’s—does not depend to any significant extent on the Mediterranean Sea. Nonetheless, the conditions are right for Chinese companies to participate in current and future energy projects in the region, which will further increase intraregional rivalries as sides vie to attract Chinese investment (TRT World, July 19). However, if meaningful cooperation in exploring for and extracting Eastern Mediterranean hydrocarbon resources can be accomplished, this could be a catalyst for finally resolving the Cyprus conflict.