The Favored Conflicts of Foreign Fighters From Central Europe

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 15 Issue: 19

By:

Relatively few jihadist fighters have originated from Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) by comparison to the number of fighters seen from Western Europe. The networks in Western Europe are far larger, and CEEC jihadists have frequently only embarked on their path to violence after migrating to Western European nations.

However, while the number of CEEC-origin jihadists responding to the global call to fight in the name of the so-called caliphate is limited to the tens rather than the hundreds — and is likely to remain relatively small in the foreseeable future — there is another conflict that has proved to be attractive to fighters from Central Europe.

Radicalized in Germany

Christian (Krystian) Ganczarski, probably the best known of CEEC jihadists, was a convert to Islam who took up jihad in Germany. He had migrated there with his family as a young boy in 1970. Born in 1966 in a small town of Gliwice, Polish Silesia, Ganczarski belonged to an older generation of jihadist fighters, those who started their careers in terrorism within the ranks of al-Qaeda in the 1990s. In February 2009, a French court found Ganczarski guilty of masterminding the 2002 suicide bombing of a Tunisian synagogue on the island of Jerba that left 21 people dead. For this, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

In a more recent case, Karolina R, a convicted jihadist, was born in a small town in Pomerania and migrated with her Catholic parents to Bonn, Germany, later converting to Islam. The 28-year-old was arrested in March 2014 in an apartment belonging to her parents in Bonn’s Bad Godesberg district, where she lived with her 18-month-old son Luqman. In June 2015, Karolina R was sentenced to three years and nine months in prison in Düsseldorf for supporting jihadist fighters. She had provided financial assistance equivalent to EUR 11,000 (about $13,000) and three camcorders to her husband Farid S, an Algerian-born German Salafist who fought in Syria (DW, January 1, 2015). Karolina R had travelled with her husband to Syria in May 2013, but returned to Germany with their child that year and started fundraising for Islamic State (IS). Her husband used the camcorders she provided to produce propaganda films. One such film released in July 2014 showed him kicking the corpses of men killed in the Syrian city of Homs. Karolina R, who has German citizenship, did not contact Polish authorities during her trial in Germany.

Karolina R’s 20-year-old brother Maksymilian also went to Syria in May 2013 and stayed with her husband. He was also a convert and died fighting for IS near Kirkuk in Iraq in February 2015 (Fakt, February 5, 2015). Maksymilian was a fan of parkour and allegedly achieved a high level of proficiency in this activity while in Germany. He is probably the first Polish citizen known to have died fighting for IS. Although, he was soon followed by another Polish immigrant to Germany, 28-year-old Jacek S. His social background is very similar to that of Karolina R and her brother. Jacek S was born in Miastko, a small town in Polish Pomerania, but lived in nearby Kamnica. In 2005, he immigrated with his parents to Germany, where he lived in Göttingen and was granted German citizenship. In April 2016, he went to Iraq. Just over a month later, Jacek S drove a car packed with explosives into a security compound at an oil refinery near Baiji, north of Baghdad, killing 11 people and wounding 27 more (Wyborcza, August 12, 2015).

Another Polish jihadist, Adam al-N, has been serving a four-year sentence in Jordan since September 2015 (RMF24, March 24). His mother was Polish and his father Palestinian. He has both Polish and Jordanian citizenship, but was born in Wolfhagen Germany. In October 2012, he went to Syria, joined Ahrar al-Sham and later al-Nusra, though he ended up within the ranks of IS. He was detained several times in Germany during his trips back and was later deported to Poland. In summer 2015, he gave an interview — the first by a Polish jihadist fighter — to journalist Witold Gadowski, trying to explain the motives standing behind his joining IS. He was subsequently arrested in Jordan a couple months later. [1]

Domestic Troubles

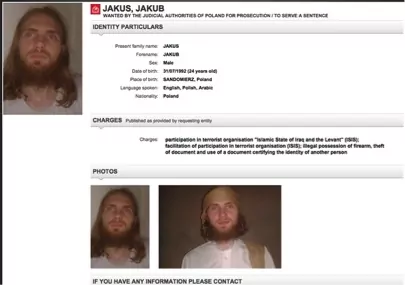

In each of these cases, Polish citizens converted to Islam and became radicalized only after their migration from Central and Eastern Europe. However, the most recent cases of Polish and CEEC jihadist fighters suggest that both the process of conversion and radicalization may have happen in Poland. Such are the cases of 25-years-old Dawid Ł. (a.k.a. Abu Hanifa), and his peer, Jakub Jakus.

Dawid Ł. is still awaiting trial in a Polish jail, while the fate of Jakub is unknown —he allegedly died fighting for IS in Syria (INTERIA, July 20,). Both were born in small towns — Dawid Ł in central Poland and Jakus in the eastern Poland. They both converted to Islam while in Poland. Dawid Ł probably completed the process of radicalization in Norway, where he emigrated with his parents.

According to the prosecution at their trial, Dawid Ł and his wife Małgorzata both went to Syria in winter 2014 and spent a year there. He joined a local Syrian militia allied to Jabhat al-Nusra near Aleppo, although he also allegedly attempted to join IS. When Dawid Ł visited Norway in April 2015, he was detained by the PST, the Norwegian security services, at the airport and finally deported to Poland in September 2015. There he was arrested.

Jakus joined IS and was wounded while fighting in Syria. There he married a local woman and was allegedly killed in action (TVN24, September 8, 2016). His conversion is believed to have taken place while he was attending a Catholic high school in the city of Lublin. He then moved to the Polish city of Łódź, where he entered his studies at the university there. While in Poland, he was a well-known Islamic activist within the ranks of the Muslim League. He paid a visit to Mecca in summer 2012. Upon returning from Saudi Arabia, he quit university and emigrated to Norway. There he was likely recruited with David Ł through members of the local organization Profetens Ummah.

From Norway, Jakus travelled to Syria in June 2013, with three other members of Profetens Ummah, one of whom later died there. On March 1, the SITE Intelligence group reported that a jihadist fighter known as Abu Khattab al-Polandi had been killed in Syria. A photograph of the dead fighter showed a young, bearded male with long blonde hair (Wiadomosci, March 2). He was not identified, though it is thought to have been Jakus.

Both Jakus and Dawid Ł were connected to a larger group of Salafists who travelled from Poland to Syria — some of them were born in Polish families, others were born abroad but with Polish citizenship (TVN24, August 27, 2016). Dawid Ł’s upcoming trial will likely provide the public with more information on this “network” connected to one of Warsaw’s mosques. The separate trial of a group of Chechens who were involved in fundraising and buying equipment for their “brothers” fighting in Syria is another example of Poland’s jihadist networks (Onet, October, 27, 2016). Estimates of the number of Polish jihadist fighters varies between 20 and 40. However, this number could certainly be larger, as not all will be known to the security services. Nevertheless, the Polish authorities do not yet consider Polish jihadist fighters as posing a severe threat to the country’s security.

The small number of cases means that overall the CEECs do not perceive returning jihadist fighters as a serious threat. Jan Silovski, a 22-year-old Czech from the small town of Třebíč, was recently sentenced to six years in prison for attempting to travel to Syria to join IS (Novinky, July 13). He converted to Islam four years earlier, and he appears to have been radicalized through contact with jihadist propaganda online. According to Miroslav Mares, a Czech expert on terrorism: “What’s interesting here is that, apparently, the man had no ties with the Muslim community and is an ethnic Czech. (…) In the 1990s, people like Silovsky might have become neo-Nazis. But today, it’s groups like IS that seem to attract them.” [2]

In February, Silovski flew from Prague to Gaziantep in Turkey. He wanted to reach Jarabulus, Syria, which was then under IS control. During a stopover in Istanbul, Turkish police officers detained him, and ultimately the Turkish authorities returned Silovski to the Czech Republic. There he was investigated, charged and sentenced.

Information is not yet available in open sources on Slovakian and Hungarian jihadist fighters, though Salah Abdeslam, one the Paris attackers, is known to have spent three weeks in the Slovakian city of Nitra in the summer of 2015. He reportedly was connected to Slovakia via one of his relatives, who had married a Slovak woman (Spectator, April 6, 2016). Also, a number of would-be fighters travelling to Syria via Hungary have been arrested there by counterterrorism authorities (France 24, January 14).

A Battleground Closer to Home

Global jihad is not the only option available to aspiring CEEC fighters. Their immediate neighborhood has a violent conflict that attracts hundreds of volunteers from across Europe — Ukraine. The Ukraine conflict has yet to draw the same number of foreign fighters that IS has managed to attract. Even so, approximately 17,000 fighters from 56 countries have already taken part in the conflict, more than 2,000 of them non-Russians.

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the first recorded instance of foreign fighters in Ukraine were the Serbian Chetnik Brigades, which were comprised of Bulgarians and fighting in support of the Russian forces.

The factors that affect the influx of foreign fighters and their radicalization — whether fighting alongside Russian forces or against them — include the existence of extremist ideologies, the activity of paramilitary groups, the weakness of state structures and the geographic position of Ukraine. [3]

Central European countries are directly adjacent and well connected to Ukraine. As a result, they have become transit countries for fighters who visit them for either recreational purposes or to promote their activities. Militants from Finland, Norway, France and Austria have traveled to Ukraine via Central Europea by air and land. A group of Chechens from Denmark crossed the Polish-Ukrainian border illegally in 2015, and in 2017 the Polish border police stopped Austrian Benjamin Fisher, who was wanted for war crimes in Ukraine. Fisher had previously fought in Syria and Iraq among the ranks of the Kurdish Peshmerga, and he had served in the Austrian military. [4]

Moreover, some groups of foreign fighters in Ukraine, such as so-called Tactical Group Belarus, are organizing open meetings, crowdfunding campaigns and paramilitary training in Central European countries.

Citizens of Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia — and indeed of Hungary, albeit on a smaller scale — form a distinctive group of foreign fighters in Ukraine. They are attracted by the geographical proximity of Ukraine, and benefit from having good knowledge of the internal situation in the country, as well as a relatively good knowledge of the Russian and Ukrainian languages.

The main reason given by Polish fighters for taking part in the Ukrainian conflict is their personal feelings toward Russia or Ukraine. On the side of the separatists are those with pro-Russian views, who perceive Ukraine as being run by a neo-fascist regime. They emphasize the historical misdeeds of Ukrainians toward the Poles, chief among them the ethnic massacres of the 1940s. On the other hand, those who fight on the Ukrainian side perceive Russia as an existential threat to Poland and treat Ukraine as the frontline of a struggle against a common enemy. Ukraine is a popular destination among radical Polish right-wing organizations, such as the National-Radical Organization (ONR) and Great Poland Organization (OWP), as well as neo-fascist organizations such as Falanga, which underlines their desire to take up historically Polish territories from Ukraine such as Lviv.

Czech and Slovak fighters who often form common paramilitary task forces in Ukraine share many common characteristics: a negative attitude toward the EU, NATO and liberal democracy; subscription to a pan-Slavic ideology; and military experience (many are veterans with experience from Kosovo and Afghanistan). Many Czechs are familiar with military service, having worked in their country’s professional armed forces. Some are experts in martial arts — Paweł Botka, a mixed martial arts (MMA) professional, fought in a unit of foreign fighters on the side of pro-Russian separatists. [5]

Many Slovaks fighting in Ukraine have military experience they acquired in the ranks of the Slovak armed forces. Additionally, some fighters have been convicted of criminal activity or of involvement in the activities of extremist political groups, such as Mario Reitjman, who has been frequently written about in the Slovak press. [6]

In another instance, a Slovak fighter who wanted to take part in the conflict on the side of the separatists found that he required a Russian visa. Since he failed to qualify, he instead travelled to Ukraine and became a volunteer with the Azov Regiment, a group fighting against the separatists. While amusing, the story also serves to show how the conflict in eastern Ukraine attracts people whose primary interested is militancy, regardless of politics. [7]

A Combination of Factors

Participation of the CEECs’ fighters in the Ukraine conflict is a culmination of many political, ideological, religious, ethnic and historical factors. Their presence in the conflict provokes a dangerous transnational social radicalization. It has the effect of strengthening transnational contacts between radicals and leads to the infiltration of foreign security services. It also results in negative social consequences such as increased instances of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or as those coming out of the Ukraine conflict term it “Donbass syndrome.”

Moreover, many of the foreign fighters in Ukraine are already experienced, having fought in other conflicts around the world. Many of them go on to join other battlegrounds — some have travelled on from Ukraine directly to Syria and Iraq.

NOTES

[1] Witold Gadowski, “Polak w szeregach ISIS – wywiad”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QF9qrp_-TYM&t=358s

[2] Miroslav Mares quote from “Czech Is Sentenced to Prison for Trying to Join ISIS”, by Jan Richter, (New York Times, February 24)

[3] For more information about foreign fighters and the phenomenon of the “ideological traverse” in Ukraine, where Communists and Nazis fight “arm in arm” see: Arkadiusz Legieć, “Profiling Foreign Fighters in Ukraine – Theoretical Introduction”, in: Kacper Rękawek, [ed.] Not only Syria? The Phenomenon of Foreign Fighters in Comparative Perspective. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series – E: Human and societal Dynamics, IOS Press, Amsterdam, 2017, https://www.iospress.nl/book/44928/.

[4] Holmsted Larssen Chris, Danish Foreign Fighters: Past and Present Patterns. W: Not Only Syria? The Phenomenon of Foreign Fighters in Comparative Perspective. IOS Press, Amsterdam, 2017, https://ebooks.iospress.nl/volume/not-only-syria-the-phenomenon-of-foreign-fighters-in-a-comparative-perspective

[5] Prague Monitor, Aktualne.cz: Czech man fighting among separatists in Ukraine. Prague Monitor (July 28, 2015)

[6] Dennik, Slovenski zoldnieri na Ukrajinie, ich usilovni pomocnici a nase slovenske Kocurkovo. Dennik, (January 23)

[7] Rękawek Kacper, Człowiek z małą bombą. Wydawnictwo Czarne, Warszawa, 2017