Filat’s Reset: Moldovan Prime Minister Reaches out to Putin and Medvedev

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 167

By:

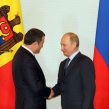

Moldovan Prime Minister Vlad Filat’s September 10–12 back-to-back visits with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (see accompanying article) amount to a reset of bilateral relations initiated by Filat. This marks the first time since 2003 (Kozak Memorandum’s collapse) that Putin deigns to receive a Moldovan leader. It also marks Medvedev’s first ever meeting (other than at CIS collective summits) with a Moldovan leader during Medvedev’s years as president and prime minister of Russia.

This is also Filat’s first visit with Russia’s leaders in the three years since the start of Filat’s prime ministership. He had sought these meetings and worked persistently to obtain them, aiming to restore both order and civility in the high-level dialogue with Russia. Moscow has apparently concluded that Filat had managed to stabilize Moldova’s governing coalition, after the years of perpetual elections and unpredictability in Chisinau.

Throughout this time, the Kremlin seemed to act as if there were no politicians worth dealing with in Chisinau. It was not until April 2012 that Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, meeting with Filat in Chisinau, recognized (and presumably informed the Kremlin) that “Filat is a man we can do business with” (see EDM, April 20). This is taken to mean that the Moldovan prime minister is a national leader capable of delivering on agreements made (a conclusion shared also from a European perspective in Brussels and Berlin).

European leaders such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel and members of the EU Commission have invested politically in Moldova’s European integration project and in the prime minister’s leadership. This project’s success requires stability and predictability in Moldova’s relations with Russia, as well as reach out to Transnistria. Brussels and Berlin are encouraging Chisinau accordingly.

But there is also a domestic political dimension to Filat’s Russia reset. No Moldovan political party can achieve an electoral majority unless it captures a sizeable share of voters among Moldova’s ethnic communities (“Russian-speaking”) or those among whom Russia (and indeed the Kremlin leaders) remain popular.

Filat’s talking points reflected those external and internal political considerations in his Moscow and Sochi meetings with Putin and Medvedev. The Moldovan prime minister elaborated on why Moldova’s European integration course cannot damage Russia’s interests and conversely, growing trade with Russia can be fully consistent with Moldova’s goal to sign an association agreement with the EU in the second half of 2013 (Moldpres, Interfax, September 10–12; Kommersant, September 10, 12).

The Kremlin is not unresponsive to the Moldovan government’s overtures. The Russian ruling “tandem” not only received the prime minister in back-to-back meetings but added a few deliverables to that symbolism. Televised messages from those meetings informed the Moldovan public that Moldovan wines are again allowed to enter Russia’s market in large volumes, with ten percent market share at present (Russia had closed its borders to Moldova’s number one export article from 2006 onward).

On the eve of his Russia visit, Filat had met with leaders of Russian cultural associations in Chisinau in the presence of the Russian ambassador. The prime minister also held detailed consultations with wine growers and food-processing firms interested in re-entering Russia’s market and promised to seek visa regime simplification for Moldovan guest workers in Russia (Moldpres, September 8, 9).

In sum, Filat is emerging as the Moldovan politician most effective at handling relations with Russia and delivering practical results. This role in inter-state relations may well result in electoral gains at home.

An official commission of Russian and Moldovan historians, to study thorny issues, was set up during this visit. The co-chairman for Moldova, Gheorghe Cojocaru, is the author of Moldova’s first-ever officially mandated report condemning Communism in Soviet Moldova (“Cojocaru Report” in 2010).

The Transnistria conflict went almost unmentioned (at least publicly) during the visits with Putin and Medvedev. Chancellor Merkel—co-signatory with Medvedev of the 2010 Meseberg Memorandum, which attempted to create a parallel negotiation on Transnistria—had visited Chisinau on August 22, with the Meseberg initiative on her agenda (see EDM, September 5). On September 10, the first day of Filat’s Russia visit, Merkel held a telephone conversation with Putin at her initiative. The Kremlin’s announcement did not mention the Transnistria topic (Intefax, September 10).