Former Editor-in-Chief of Lenta.ru Launches New Media Project From Latvia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 189

By:

Galina Timchenko’s new Russian-language news media project, the website Medusa (medusa.io), was launched on October 20, in Riga, Latvia. Timchenko’s project became an intriguing topic in the Russian press after she was fired this March from her position as editor-in-chief of the news agency Lenta.ru, which is owned by the Rambler Media Group. Thirty-nine Russian journalists lost their jobs along with her. In a joint statement the fired journalists wrote that they interpret the owner’s actions as “direct pressure” aimed at eliminating independent reporting in Russia by appointing new editors and journalists “controlled directly from the Kremlin” (lenta.ru, March 12)

Formally, the reason for Timchenko’s dismissal was a warning from the Russian executive agency Roskomnadzor, which observes media and communication laws (lenta.ru, March 12). In March of this year, Roskomnadzor launched a criminal investigation accusing Lenta.ru of extremism for publishing an interview (lenta.ru, March 10) with Andrei Tarasenko, a Ukrainian politician and one of the leaders of the far-right organization Pravy Sector (Right Sector) (see EDM, March 13).

Under Timchenko’s leadership (2004–2014) Lenta.ru became Russia’s most cited news source according to the Harvard Berkman Center (cyber.law.harvard.edu, October 18, 2010), with over a half a million daily visitors. But with Timchenko gone, Lenta.ru has come to resemble the Russian pro-Kremlin media, releasing content remarkably similar to that published by government-controlled outlets in Russia. Consequently, Lenta.ru continues to lose its international prestige (br-analytics.ru, July 4).

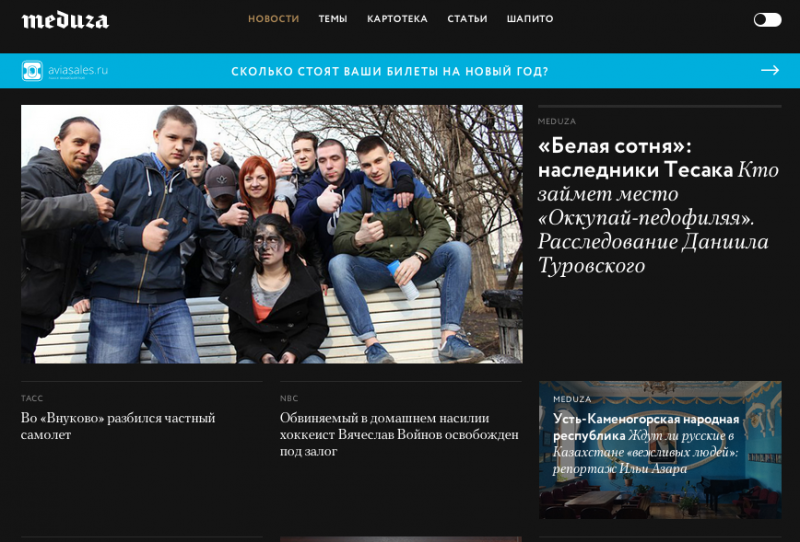

This summer, Timchenko announced that her new media project, Medusa, would be launched in October. She underlined that her news outlet will aim to unite her old colleagues fired by Rambler. Her new product is much smaller compared to the gigantic Lenta.ru, and also the Medusa website publishes considerably less original material, relying more on reposting articles from other places across the web. This makes Medusa a form of hybrid media—partially posting their own products but, nevertheless, functioning as a classic content aggregator. Currently, Medusa’s webpage hosts widgets for the Russian news agencies RIA Novosti, RBK and TASS, Dozhd, the Ukrainian agency UNIAN, as well as American ESPN and Politico—the last two translated from their original English into Russian. “Our project has a mantra—to provide a minimum subsistence of Information. [Medusa] will [present] a snapshot of the day, [illustrated] with the most essential and best written texts in the Russian language,” Timchenko said in a September interview to the Russian edition of Forbes. In the same interview Timchenko admitted that Medusa would be an aggregator, but she underlined that it would not rely on a robotic automated collection of information. “[A]ll information will be [thoughtfully] handpicked by our editors, depending on its importance and relevance,” she said (forbes.ru, September 15).

Despite Timchenko’s level of ambition and professionalism, finances seemed to be the key stumbling block since the announcement of her idea. Indeed, inadequate monetary resources continue to affect Medusa’s limited ability to produce original content. During their media appearances, Galina Timchenko and her partners are often asked specifically who the investors in Medusa are. But they always refuse to reveal any names, except for mentioning the famous Russian oligarch and now dissident Michail Khodorkovski, who did not end up financing the project at all. According to Timchenko, Khodorkovski initially expressed “business interest” in Medusa. However, further negotiations failed to produce a desirable result, she noted, due to “disagreement about the level of investor control over editorial policy” (Izvestia, August 27). Another failed attempt to secure outside investment involved the son of the founder of Russia’s giant communication company “Vympelcom,” Boris Zimin. He was also seeking more involvement in editorial policy than Timchenko would tolerate.

Medusa needs to secure a $1 million dollar annual budget to meet the standards Timchenko wishes to uphold, says the prominent Russian blogger Anton Nosik. There is a possibility that Galina Timchenko’s idea will become yet another marginalized project unless new investors emerge, and they are not likely to emerge in Russia, at least not those who would respect Timchenko’s demands for maintaining the news site’s independent editorial policy (Izvestia, August 27).

In her public statements, Timchenko stresses that she and her Medusa project are not pursuing any political agenda and are not taking sides on political issues. The idea is solely to create a free, reliable news outlet. However, in reporting on her latest endeavor, Russian media continually highlight the location Timchenko chose to move to—Riga, a capital of one of the “evil” Baltic States, portrayed by the Kremlin as a “Western satellite” whose regime discriminates against ethnic Russians (rbcdaily.ru, May 5). Medusa, as any other Russian-language outlet reporting from Latvia, cannot possibly be impartial or politically independent, many bloggers and even news outlets in Russia repeatedly argue (ridus.ru, October 7).

Timchenko responds to such accusations by explaining that Riga was a “practical” rather than political choice. The Latvian capital lies in close proximity to Russia’s urban centers, offering ease of travel and a minor time difference with Moscow, among other key reasons she cites. She also underlines that she never meant, let alone planned, to emigrate from Russia. But under the current circumstances, she sees no way for an independent media outlet to survive inside the Russian Federation.

The state of the Russian press today is a consequence of a whole series of “compromises” made by media owners in order to keep the Kremlin happy, Timchenko says in her essay posted on Latvian news outlet Spektr (spektr.delfi.lv, July 23). The name of her article speaks for itself: “The way into the abyss.” As the country’s free speech and media environment continues to close further (see EDM, March 13, October 2, 23), it remains to be seen how many of Russia’s other journalists will start to actively follow Timchenko’s example.