Hungary: China’s Gateway to the EU Market

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 16

By:

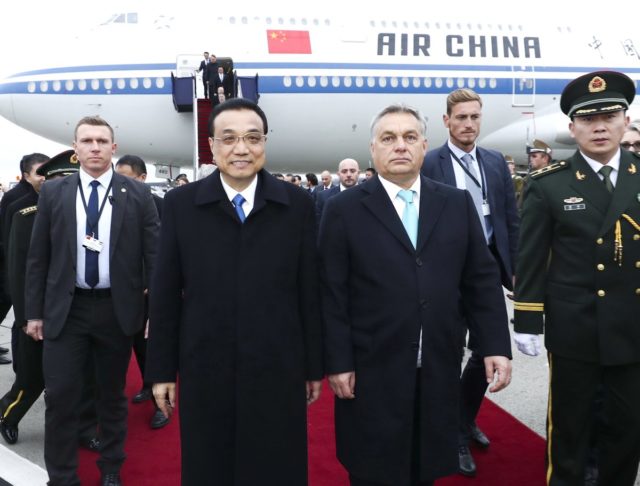

On November 24, Li Keqiang, China’s premier and top economic official, arrived in Budapest to great fanfare (China Economic Daily, November 29). Although Hungary is not typically on lists of major economic partners for China—even maps of the trans-Eurasian Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) skip over Hungary in favor of nodes in Greece or Italy—it has emerged as a key entryway for Chinese goods into the European market.

While Chinese coverage of the visit has trumpeted a number of trade deals, a review of China and Hungary’s economic relationship indicates that China has little to gain directly from the partnership. Instead, China is playing a longer-term, strategic game.

In 2016, China was the destination of only $2.2 billion worth of Hungarian exports—2.25 percent of its total exports. For context, Hungary exports $3.5 billion worth of goods to the United States. China is more interested in the countries that Hungary trades with, like Germany, which had exports to China worth $85 billion (Atlas of Economic Complexity [accessed November 30). This makes China Hungary’s largest non-EU trading partner (MOFCOM, August 3). Meanwhile, China sold Hungary more than double that amount worth of widgets: fixtures, lights and other oddments that Hungarian workers then assembled into larger products for exports. Therefore, while Li and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban tout expanding Hungarian exports—especially of agricultural products—the reality is that China has always bought more Hungarian chemicals than it has fruit or grain.

The bigger story then is geopolitics and Hungary’s role as a hub and entry point to the European market for Chinese goods.

Li’s primary purpose for the visit was the sixth meeting between China and the heads of state of 16 Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC)—the so-called “’16+1’ cooperation mechanism.” China has been explicit about its goals for Hungary. When previous Premier Wen Jiabao’s visited Hungary during the first 16+1 meeting in 2011, he bluntly admitted that Hungary was to be an entry-point to the richer European market (China Brief, July 15, 2011). After the unveiling of the Belt and Road in 2013, Hungary took on even greater significance as commercial projects became part of a prominent national strategy (China Brief, January 9, 2015).

In May, Hungary held Europe’s first “Belt and Road Forum.” Speaking at the forum, Daniel Palotai, Chief Economist at the Hungarian National Bank, noted that Hungary has already become a de-facto clearinghouse for Chinese currency, and that Hungarian financial institutions are eager to cooperate with BRI projects (China Economic Daily, May 26). In the short-run, Hungary provides immediate and convenient market access to the EU for Chinese goods and a favorable investment climate.

However, there is a longer-term component at work as well. The Belt and Road Initiatives is meant to create work for Chinese state-owned enterprises, but also to create efficiencies that lead—long-term—to better, more prosperous trading partners for China.

Investment in Hungary advances both of these goals. Chinese staff at the Central European Trade and Logistics Cooperation Zone highlighted Hungary’s value as a logistics hub, noting that seven major highways branch out of Budapest, connecting it to 480 million consumers within 1000 kilometers (621 miles) (China Trade News, July 6, 2017). Most importantly, 10 of the countries within that range are EU members.

To make these deals more palatable—and improve the ability of Chinese goods to move inter-regionally—China is now funding improved rail links. This includes a line between Budapest and Belgrade that, when completed in 2019, should reduce travel times from eight to two-and-a-half hours (China Daily, August 16). Eventually, the railway will also link to the Greek port Piraeus, offering an efficient path for seaborne trade directly into the heart of Europe.

For Central European governments another major attraction is the possibility of greater north-south connectivity. Traditionally, the major highways and rail lines in Europe have gone from east to west. While these links were useful for moving goods to the more developed economies in Western Europe, the lack of corresponding north-south links acted as a bottleneck for improving trade among the eastern and central European states. China’s appetite for investment in large infrastructure projects offers a solution to this historical problem and could make eastern and central European economies more competitive.

As in the case of the Ethiopia-Djibouti rail links, improvements to inter-regional rail extend beyond the positive effects for Chinese trade and could be both politically popular and have a major benefit to local economies (China Brief, November 10).

Longer term, Chinese investment and attention to the less-developed economies in Central and Eastern Europe will probably pay off. Governments looking to reduce their reliance on powerful neighbors (as Hungary does on Germany), or political parties which have been criticized by liberal states (as Orban’s Fidesz Party has) will continue to find China an attractive ally.

In the end, to maintain growth long-term China must build bridges—politically and literally—in countries like Hungary.