Hungary Signs South Stream Project Agreement

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 7 Issue: 21

By:

On January 31 in Budapest, Russian and Hungarian officials signed the project agreement for the construction of Gazprom’s South Stream pipeline on Hungarian territory. Hungary’s privately-owned MOL Company, a member of the Nabucco consortium, is not a party to the South Stream agreement. Hungary participates in South Stream on the state level through the Hungarian Development Bank (HDB: Hungarian acronym MFB), 100 percent in state ownership. The signing of the project agreement was expected, although delayed by almost one year since the signing of the framework agreement in March 2009 under the previous Hungarian government.

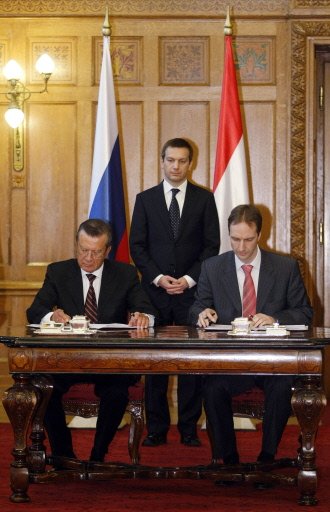

Gazprom Vice-President Aleksandr Medvedev and HDB president Janos Eros signed the project agreement in Budapest, witnessed by Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Viktor Zubkov and Hungarian Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai, who heads a non-political caretaker government, pending new elections in Hungary. The agreement establishes the project company South Stream Hungary, which is authorized to commission the feasibility study, raise the financing, build, and operate the South Stream pipeline’s section on Hungarian territory, with a throughput capacity of no less than 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year.

The project company is being incorporated on a 50-50 parity basis, with its headquarters in Hungary, and a four member board composed of two representatives for each side, and a rotating chairmanship. Gazprom and HDB pledge not to participate in any other project that aims to transmit natural gas via Hungary to markets in southern Europe. The project company’s registered capital is a mere 50 million Forints (MTI, Interfax, January 29).

The feasibility study is being commissioned to a joint company created by Gazprom and MOL for this purpose. While MOL is not involved in South Stream as such, the company participates in the feasibility study in a technical role. At the South Stream signing ceremony, Bajnai declared that “Hungary must seize every concrete opportunity to diversify its energy supplies” (MTI, January 29). Given Hungary’s total dependence on Russian-delivered gas, Bajnai’s statement can only be understood as referring to projects other than South Stream.

The European Union-backed Nabucco project holds first place among the Hungarian government’s declared priorities on energy policy. The Hungarian government’s Nabucco coordinator, Mihaly Bayer, has stepped into the leadership vacuum that the EU has allowed to develop on Nabucco during the transition from the old commission to the new. The Hungarian parliament is the first (and, thus far, only) to have ratified the Nabucco inter-governmental agreement among five Nabucco participant countries.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the planned Adriatic LNG terminal via Croatia holds second place among Hungary’s declared energy policy priorities. South Stream ranks only third. Nevertheless, it is moving ahead with strong political support from the Kremlin, amid international procrastination on Nabucco and the LNG project.

The Kremlin and Gazprom have negotiated agreements with six or seven countries for South Stream (and are now inviting more countries) but have never identified gas reserves in Russia or elsewhere for supplying this project. The January 29 signing event in Budapest was no exception in this regard.

In the short time span from late 2008 and mid-2009, Moscow increased South Stream’s aggregate gas offer from 31 to 63 bcm, and its cost estimate from $9 billion to more than $25 billion. It conducted no feasibility studies to substantiate such an offer, never showed gas earmarks for it, and had no answer about financing such costs.

Meanwhile, Gazprom itself anticipated a gas shortfall (stagnant production versus growing supply commitments) in 2008, temporarily reprieved by falling demand during the recession, but looming in the post-recession period. Gazprom’s latest board meeting half-admitted this situation. Nevertheless, it scheduled continuing expansion of pipeline projects, without financing new field development to fill the pipelines (EDM, January 29).

Moscow proposes to build pipeline capacities far exceeding Russia’s own export potential in the years ahead. South Stream is a centerpiece of this declared policy. Given its lack of identified gas reserves and financing, this project may be assessed as a political bluff, as well as an anti-diversification project. It seems mainly intended to discourage investment in Nabucco (and the overall Southern Corridor) and introduce new political complications to the EU’s energy policy.

Yet, governments are signing up to South Stream as the EU-backed alternatives have yet to materialize, US leadership is fading, and national electorates expect their governments to demonstrate a proactive approach to energy security. Thus, Russia has generated a band-wagon effect for South Stream in south-eastern and central Europe (Romania excepted).

South Stream and Nabucco cannot be described as competing projects, if only because Nabucco does have gas reserves earmarked for it (pending the transport solution), whereas South Stream does not. Thus, countries that sign up to South Stream do not thereby jeopardize Nabucco, which (as in Hungary’s case) they strongly prefer and support. What does jeopardize Nabucco is the current lack of coordination from Brussels. Governments in the Nabucco supplier and transit countries expect the new EU Energy Commissioner, Guenther Oettinger, to address this issue urgently as he takes office this month.