Issues of Centralization, From Financial Work To Personnel

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 20

By:

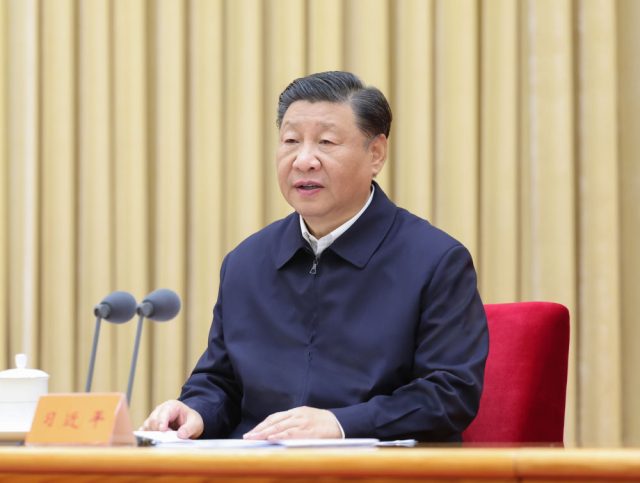

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping called for tighter Party and state control of the financial sector in the quinquennial Central Financial Work Conference that ended in Beijing on October 31 (Xinhua, October 31). All seven Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) members as well as provincial leaders and the heads of financial and securities regulatory units participated in the conference. Stressing that party authorities should exert more oversight over the nation’s banks and other financial institutions, the general secretary vowed to make “greater efforts to comprehensively step up financial supervision, optimize financial services, prevent and resolve risks so as to promote high-quality development of China’s financial sector” (Xinhua, October 31; CGTN.com, October 31; Bloomberg, October 23).

In his speech to the conclave, the supreme leader also cautioned that financial supervision should be effected under the principles of “seeking progress while maintaining stability, taking one step at a time, and avoiding excessive ambition or [relying too much] on foreign [models].” Xi emphasized that adequate funding be devoted to establishing a “modern industrial system” based on the “real economy (实体经济).” Following Beijing’s long-standing industrial policy, more resources will be earmarked to high-tech areas such as information technology, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, new materials, advanced pharmaceuticals, and drivers of the “green economy” such as electric cars (Gov.cn, August 22; Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 23).

Yet the “CCP core for life” has not made much reference to more pressing issues such as restructuring the overleveraged real estate sector or mitigating the heavy indebtedness of nearly all local administrations. Top real-estate corporations such as Evergrande have run up debt totaling more than Renminbi (RMB) 2.4 trillion (approximately $330 billion), and nothing has been done to help the tens of thousands of Evergrande customers whose prepaid apartments remain unfinished—or the foreign investors in related bonds. Moreover, the lack of sufficient funds to handle withdrawals from depositors at financial institutions in areas including Hebei and Guangdong have caused runs on medium-sized state-owned banks (Asia Times, October 14; French Radio International Chinese, October 12).

Stasis and the State in Financial Policy

In even worse shape than housing giants are local administrations and their heavily indebted investment vehicles. Latest estimates show that administrations at the provincial, municipal, and county levels have raised loans totaling RMB 98 trillion (nearly $13.5 trillion). At least half of the annual income of these local governments—which have been excessively dependent on land sales and related taxes—is being used merely to service interest on their loans and bonds. At the Central Financial Work Conference, Xi pledged a “long-term mechanism” to restructure and resolve regional debt. In late September, Beijing kicked off an RMB 1 trillion ($137 billion) debt swap program to allow local administrations to replace their so-called “hidden debt” for bonds carrying lower interest rates. Last week, the government also announced a separate, unusual RMB 1 trillion central government bond issuance to support local spending (Caixin.com, November 1; Bloomberg, November 1). Given the tendency of local governments to float new loans and bonds to cover old borrowings, the prospects of a short-term resolution to the problem seem bleak.

Xi’s team has also failed to address the critical issue of a severe decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) into China, which is one reason why funds in many industrial sectors are drying up and exposure to global technology has been stymied. From January to September 2023, FDI was a mere $125.75 million, a drop of 8.4 percent from the same period in 2022 (Trading Economics, October 20). In the meantime, funds—mainly US dollars—being remitted overseas by enterprises and individuals keen to leave the People’s Republic of China (PRC) reached $54.9 billion last month, the largest outflow since January 2016 (Nikkei Asia, October 25).

Of perhaps even more significance for the future of reform is the Xi administration’s efforts to de-marketize the whole real estate sector to revive the pre-1994 system of Party cells and administrative offices distributing subsidized housing to their members or workers. According to an exclusive report by the state-run Economic Observer Net, the State Council recently distributed Central Document No. 14, entitled “Guiding Opinion Regarding the Planning and Construction of Affordable Housing (关于规划建设保障性住房的指导意见),” that would significantly revive the pre-reform practice of government and public units selling or renting out subsidized housing to their workers. According to the Document, the resuscitation of the system of subsidized housing (保障房) is based on the principle of “the affordability for wage earners, and the balance and sustainability of funding [used for these projects]” (Eeo.com.cn, October 16; South China Morning Post [SCMP], August 18). Experts recruited from all over the country to a particular locality are also entitled to subsidized housing. Observers have noted that while normal “commodity housing (商品房)” will still be retained, these units are mainly meant for higher-income workers and members of the middle class. The model for giving out “subsidized housing (保障房)” for the general working class—and leaving so-called “commodity housing” for the relatively rich segment of the population—bears resemblance to the well-known housing models adopted in Singapore. [1]

Experimentation with the resuscitation of the Maoist principle of the de-commercialization of housing has already taken place in Xiong’an, Xi’s model city for the future based just outside Beijing (People’s Xiong’an Net, February 6). What many Chinese residents worry about, however, is that those who have already purchased “commodity housing”—even if such housing is still under construction—might not be eligible for the subsidized housing that several dozen cities have started to build. Moreover, the Xi and the CCP leadership has yet to ensure that failing real estate giants such as Evergrande and Country Garden will be obliged to sufficiently compensate dissatisfied customers.

Personnel Issues at the Heart of Policy Stasis

Xi’s apparent failure to introduce more market-oriented measures to restructure key sectors such as real estate and banking could reflect an ongoing series of high-level personnel-related events, which cast doubt on the paramount leader’s control over his top brass in both the civilian and military sectors.

On October 26, Xi sacked state councilors General Li Shangfu (李尚福) and Qin Gang (秦刚), who had also held the titles of defense minister and foreign minister, respectively. No explanation has been given for the sudden disappearance of the two men, who were once considered protégés of the supreme leader. The Party and government have also left the public in the dark regarding investigations into scores of senior military cadres in the equipment procurement departments, the Rocket Force, as well as the diplomatic establishment. These organs have been accused of corruption and the leaking of state secrets to Western nations, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Qin was replaced by his old boss Wang Yi (王毅), the former foreign minister who was promoted to the Politburo at the 20th Party Congress in October 2022. Despite his reputed closeness to the PLA top brass, Xi, who is commander-in-chief, has so far failed to find a replacement for General Li. This became awkwardly apparent as Beijing hosted an annual international defense forum at the end of October (BBC Chinese, October 26; VOA Chinese, October 24; Xiangshan Forum, accessed November 2).

The unexpected death of former premier Li Keqiang (李克强), who was a member of the PBSC from 2007 to 2022, provides a stark reminder of both the confusion and opacity of CCP elite politics and Xi’s apparent disdain for market-oriented reforms. The large-scale and spontaneous mourning of the 68-year-old Li has posed a threat to the legitimacy and stability of the Xi Jinping regime. Although public remembrance activities have been largely confined to Hefei, the capital of Anhui Province where Li was born in 1955, this was due to the decision by President Xi and the CCP Propaganda Department to scrub clean all references to Li in the social and mass media. Police in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai have also been mobilized to stop mass gatherings commemorating the former premier (BBC Chinese, October 31; Radio French International Chinese, October 28).

Li was the last PBSC member to have openly advocated the continuation of reform and opening, the signature policy of Deng Xiaoping, China’s chief architect of reform. On a visit to Shenzhen—the first special economic zone established by Deng—several months before stepping down as head of the central government in March, Li said that reform must go on, “just as the [direction of the flow] of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers cannot be reversed” (United Daily News, October 27; VOA Chinese, August 22). Li, who became premier in March 2013, was sidelined from major decision-making on economic issues within a year of taking office—a move away from the norm that the premier oversees all financial and economic decision-making in the country. Any outpouring of grief by members of the public could be seen as unmistakable support for Li’s (and by extension Deng’s) reform policies. On the contrary, Xi’s apparent nervousness about the popularity of the late premier, who from 2012 to 2022 was the highest-ranked PBSC member after Xi, suggests that the supreme leader sees his grip on power as less than assured (VOA Chinese, October 30; Radio French International Chinese, October 29).

Conclusion

The Xi administration has disseminated a toned-down verbal eulogy of Li, but has decided not to hold any public mourning ceremony. This stands in contrast to the funeral arrangements that followed the death of former Party Chairman Jiang Zemin (江泽民) in December 2022. The train of events surrounding Li’s death has compounded the impression—particularly among foreign investors—that elite politics in China is as opaque as it is cold-blooded. In terms of immediate impact, it is difficult to see how Li’s departure and the disappearance of Qin Gang and Li Shangfu could affect the CCP’s policy direction, given that the overall trajectory is set by Xi. However, there will be a longer-term detrimental effect, both on the quality of policymaking and on Xi’s authority, particularly his ability and willingness to push market-oriented policies. His apparent inability to tackle severe economic challenges head-on, such as a collapsing housing market and the heavy indebtedness incurred by state-owned enterprises and local governments, will hardly burnish the reputation of the “leader for life.”

The deaths and disappearances at the highest echelons of the Party in recent months echo the silence in the policymaking domain. The underwhelming outcome of the Central Financial Work Conference suggests that the leadership is waiting to see how its current batch of policies play out over the coming months. But it also suggests that the leadership is low on ideas, or at least on the willingness and capacity to implement them: Old tools—like financial support to the real estate sector and anti-corruption to mitigate some of the financial sector’s problems—do not constitute the fix that China’s economy needs.

Notes

[1] Stephan Ortmann & M. Thompson, “China’s Obsession with Singapore: learning authoritarian modernity”, Pacific Review, v.27, 2014, Issue 3, pp.433-55.