Beijing Announces Its Intention to Impose a New “National Security” Law on Hong Kong

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 10

By:

Editor’s Note: This article was initially published as a Jamestown “Early Warning Brief” on May 26. It has since been updated for re-publication here.

Introduction: Beijing Introduces Draft “National Security” Legislation for Hong Kong

For many weeks, People’s Republic of China (PRC) authorities in Beijing have signaled their intent to seek tighter control over Hong Kong—whether through the imposition of “patriotic education,” personnel appointments, or changes to the territory’s legal system (China Brief, December 10, 2019; China Brief, February 21; China Brief, May 1). This past week Beijing took a major step in the latter direction when China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) introduced draft legislation on national security for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), without going through the HKSAR legislature. The measure became official after delegates approved it in a vote at the close of the NPC session on May 28.

The “National People’s Congress Draft Law Concerning Establishing and Strengthening the Safeguarding of National Security for Hong Kong” (全国人大关于建立健全香港维护国家安全法草案, Quanguo Renda Guanyu Jianli Jianquan Xianggang Weihu Guojia Anquan Fa Cao’an), which was submitted to the NPC on its opening day on May 22, would proscribe “actions to split the country” (分裂国家的活动, fenlie guojia de huodong), “terrorism” (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi), and “subversion of state power” (颠覆政权, dianfu zhengquan). The draft, which could become law in a matter of a few months, would also prevent foreign political organizations from operating in Hong Kong, if such were perceived to be detrimental to Beijing’s interests (Caixin, May 22).

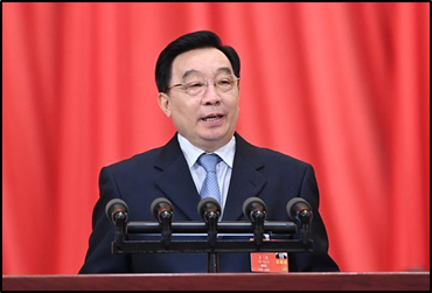

“The increasingly notable national security risks in the HKSAR have become a prominent problem,” said NPC Vice Chairman Wang Chen (王晨) at the opening meeting of the NPC on May 22. Wang cited activities that have “seriously challenged the bottom line of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ principle, harmed the rule of law, and threatened national sovereignty, security and development interests… Law-based and forceful measures must be taken to prevent, stop and punish such activities” (Xinhua, May 22).

The security bill will likely be fleshed out and officially promulgated when the Standing Committee of the NPC meets in the summer. The draft version distributed among the 3,000 deputies on May 22 stressed “taking necessary measures to establish and improve the legal system and enforcement mechanisms for the HKSAR to safeguard national security, as well as to prevent, stop and punish activities endangering national security in accordance with the law.” Countermeasures will be taken against foreign and external forces allegedly trying to interfere in HKSAR affairs. Despite the HKSAR’s well-established British-style independence of the judiciary, the legislation calls on the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the Hong Kong government to take more stringent actions to safeguard state security (People’s Daily, May 22; Caixin, May 22).

The Implications for Hong Kong’s Legal System

In the new law, the HKSAR is directed to establish and improve institutions and enforcement mechanisms for upholding “national security.” Moreover, the NPC Standing Committee will be empowered to lay down measures to improve the legal system and establish institutions in Hong Kong to protect state security. “When needed, relevant national security organs of the Central People’s Government will set up agencies in the HKSAR to fulfill relevant duties to safeguard national security in accordance with the law,” the draft law added. The HKSAR government is also charged with implementing “national-security” and “patriotic” education in Hong Kong’s schools (Ming Pao, May 23).

The Basic Law of Hong Kong, the HKSAR’s mini-constitution, allows the NPC to make laws applicable to Hong Kong by inserting them into Annex 3. The territory’s pro-democracy politicians have reacted to Beijing’s sudden move with shock. “This is the saddest day in the history of Hong Kong,” said Civic Party lawmaker Tanya Chan. “The rights and freedoms enjoyed by Hong Kong are a problem for the Chinese government… this is why China plans to destroy them.” According to Helena Wong, legislator of the Hong Kong Democratic Party, “Hong Kong’s law-making powers have been stymied by the National Security Law.” She added that the fact that there had been no consultation with HKSAR groups or politicians means that “Beijing has turned a blind eye” to the wishes and aspirations of the people of Hong Kong (Asia News.it, May 22; Post852, May 22).

One apparent reason behind Beijing’s decision to impose a national security law on Hong Kong is the failure of HKSAR authorities to promulgate Article 23 of the Basic Law—a step that Beijing’s representatives have been advocating with increasing insistence (China Brief, June 26, 2019; China Brief, May 1). Article 23 states that the Hong Kong SAR “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region.” An attempt by the Hong Kong legislature to pass the much-feared bill in 2003 resulted in more than 500,000 citizens hitting the streets in protests, and the bill was subsequently withdrawn (South China Morning Post, May 21).

There are reasons to suspect that the Hong Kong National Security Law could be even more draconian and restrictive than the controversial Article 23. For example, the new law could allow state security agencies such as the Ministry of State Security (国家安全部, Guojia Anquan Bu) to set up branches in the SAR. “State security agents could carry out tasks such as investigation, intimidation and even secret arrests in Hong Kong,” said Bruce Lui, a journalism lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University. Furthermore, since these agents report directly to Beijing, they may be beyond the control of legal authorities in the HKSAR (Apple Daily, May 22).

Reactions to the National Security Legislation

While it is debatable as to whether the Hong Kong National Security Law might lead to massive emigration of HKSAR citizens to English-speaking countries, its negative impact on business seems certain. The Hang Seng Stock Index dropped 1,349.89 points (5.56 percent) the day the draft legislation was announced. In a statement, the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) in Hong Kong said the legislation “may jeopardize future prospects for international business.” “Hong Kong today stands as a model of free trade, strong governance, free flow of information and efficiency,” said Robert Grieves, AmCham Chairman. “No one wins if the foundation for Hong Kong’s role as a prime international business and financial center is eroded” (Amcham, May 22).

Western governments have reacted to the proposed legislation with alarm. U.S. President Donald Trump said that if the proposal were to be enacted into law, “we’ll address that issue very strongly.” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called the draft legislation “a death knell for the high degree of autonomy” that Beijing had promised the territory, and stated that “the United States strongly urges Beijing to reconsider its disastrous proposal, abide by its international obligations, and respect Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, democratic institutions, and civil liberties, which are key to preserving its special status under U.S. law.” A number of U.S. officials and members of Congress have called upon Washington to abolish the special customs status granted to Hong Kong, which places the territory in a category separate from that of the rest of China (The Standard, May 22; South China Morning Post, May 22). Such criticisms are unlikely to sway Beijing, however: for Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, doubling down on restrictions on the HKSAR will not only divert attention from the woeful economy in the mainland, but also build up his reputation as a fearless nationalist prepared to thumb his nose at the Americans.

Conclusion

While the semi-autonomous status of Hong Kong has become a bone of contention in the new Cold War between the United States and China, Hong Kong organizations and individuals with a record of opposing Beijing or liaising with foreigners have the most to fear. This is true despite assurances by PRC Vice-Premier Han Zheng (韩正), the CCP Politburo Standing Committee member in charge of Hong Kong affairs, that the national security legislation “only targets a minority of people” who hurt Hong Kong and the mainland’s state security (Rthk.hk, May 23). For example, liberal legislators fear that the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic, Democratic Movements in China, which is world-famous for organizing a June 4 candlelight vigil every year, may be suppressed. Also prohibited will be their key slogan: “End one-party dictatorship in the mainland” (News Now, May 22). Pro-democracy political organizations such as the Civic Party and the Hong Kong Democratic Party might no longer be able to maintain close contact with members of the U.S. Congress or political non-governmental organizations (NGOs). American journalists, missionaries, and NGO activists originally based in Hong Kong may face frequent harassment from state security agents reporting to Beijing.

According to Amnesty International (AI), China routinely abuses its own national security framework as a pretext to target human rights activists and stamp out all forms of dissent. “This dangerous proposed law sends the clearest message yet that it is eager to do the same in Hong Kong, and as soon as possible,” said Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for East and South East Asia, Joshua Rosenzweig. “The Hong Kong government has progressively embraced the mainland’s vague and all-encompassing definition of ‘national security’ to restrict freedom of association, expression and the right to peaceful assembly” (Rthk.hk, May 25). After the passage of the National Security Law, it will be doubtful as to whether AI and other human rights NGOs will be able to maintain their operations in Hong Kong.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.