Looming Long-Term Economic Problems Stem From Kyrgyzstan’s EEU Membership

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 28

By:

It has been half a year since Kyrgyzstan officially joined the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) of Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus and Armenia. Its accession treaty took effect on August 12, 2015. That same day, Kazakhstan tore down customs controls on its border with the Kyrgyz Republic in order to comply with the EEU’s fundamental concept of the free flow of goods and services among its members. Speaking to a group of local journalists on February 3, Sapar Issakov, the head of the foreign policy section within the administration of Kyrgyzstan’s President Almazbek Atambayev, said that Bishkek “had jumped onto the last wagon of a departing train” by joining the EEU. “The situation in which a country cannot trade freely with its neighborhood is a big economic tragedy. If there are no conditions in place for the free trade of goods on a regional scale, isolation is the only possible outcome, and this is really terrible for the country in question,” Issakov noted. He stated that Kyrgyzstan should actively develop exports with a view to fully benefitting from its EEU membership (Kabar.kg, February 3; RIA Novosti, Kyrtag.kg, August 12, 2015).

A similarly optimistic analysis was delivered by Kyrgyzstan’s Prime Minister Temir Sariyev in his recent interview to the Russian news agency Sputnik, which has been widely criticized in the West for spreading Kremlin-inspired propaganda. “Our accession to the EEU was dictated by economic concerns. The refusal to do so would have negatively impacted upon a whole range of economic indicators that are key to our long-term growth dynamics,” the Kyrgyzstani premier said on February 2. Last October, Sariyev sounded far less sanguine when he warned against viewing the EEU membership as a “panacea” or as an “entry ticket to paradise.” But he then added reassuringly, “The government has always maintained that the EEU would give us the possibility to compete on an equal footing with our trade partners and would open up access to a huge common market” (Sputnik.kg, February 2; Interfax, October 1, 2015).

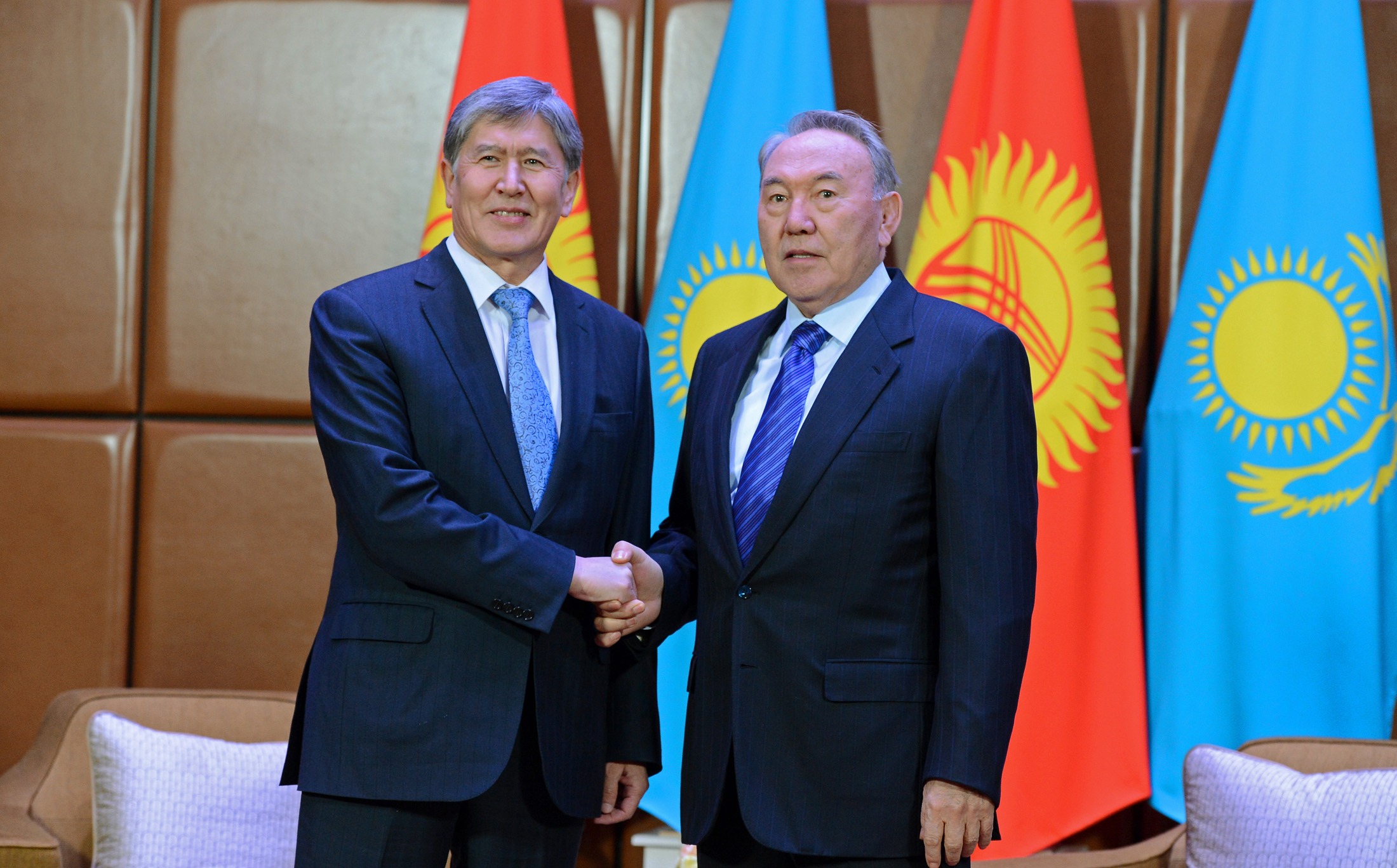

While there have been lingering debates in Kazakhstan about the pros and cons of being tied to a common integration structure dominated by Moscow, Kyrgyzstan currently seems to be enjoying relative consensus on this issue. Last year’s parliamentary elections confirmed the victory of the ruling coalition loyal to Atambayev and, therefore, of the country’s pro-Russian orientation. As such, the vote results were a clear sign of Bishkek’s willingness to stick with the EEU, at least until the next presidential election, in late 2017. Indeed, Atambayev’s “Russia card” looks significantly more appealing to his electorate than, for instance, his Kazakhstani counterpart, Nursultan Nazarbayev’s, pledges to his own supporters of closer economic integration with Russia. Unlike Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic has been able to secure substantial concessions from the Kremlin, mostly because of the geopolitical importance of the EEU for Vladimir Putin personally (see EDM, October 16, 2015).

Back in 2009, when Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus jointly laid down the legal framework for a customs union that would later expand into the EEU, Moscow provided Bishkek with a $150 million grant and a $300 million preferential loan. Three years later, in September 2012, the newly re-elected Putin administration agreed to write off $489 million of Kyrgyzstan’s sovereign debt. Moreover, between 2010 and 2015, the Russian government channeled over $185 million in aid to Kyrgyzstan to support its current budgetary operations. In 2014, the two countries further agreed to set up the Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund, with initial authorized capital of $500 million. As regards energy cooperation, since April 2014, Gazprom has been modernizing Kyrgyzstan’s natural gas distribution infrastructure. The Kyrgyzstani authorities are particularly interested in having the Russian gas giant shoulder the 24/7 supply of natural gas to the southern regions, which were rocked by violent protests in 2010, in the aftermath of an uprising in Bishkek (Kyrtag.kg, February 4, 2016; Fergananews.com, November 24, 2014).

While both Russia and Kazakhstan are experiencing severe economic problems, mostly due to their high dependence on crude oil exports, Kyrgyzstan is quietly moving forward. Its GDP grew by 3.5 percent in 2015, thanks to the better-than-expected performance of the services sector; though, industrial production declined by 4.4 percent year-on-year. The country’s currency, the som, has been traded at a floating exchange rate against the United States dollar since the 1990s. Therefore, the som has suffered less devaluation-induced damage than the Russian ruble and the Kazakhstani tenge. The latter were both pegged to the dollar—until November 2014 and August 2015, respectively—and have since shed much of their value as the price of oil has slipped further. Yet, as Kyrgyzstan draws closer to the Russian and Kazakhstani economies, it will find it harder to minimize the fallout from their respective economic crises. In 2014, Kyrgyzstani labor migrants in Russia sent home $2.1 billion, but only $325 million in the first half of 2015. Meanwhile, last year’s bilateral trade with Kazakhstan was cut in half compared to a year earlier, down to $472 million (Kyrtag.kg, February 4; Azattyk.org, January 16).

The medium- and long-term outlook for Kyrgyzstan’s membership in the EEU looks all the more uncertain, with Russia unlikely to return to a growth trajectory absent structural reforms. On January 21, the Kyrgyzstani parliament unilaterally abrogated the September 2012 agreement with Russia under which Rushydro had promised to build a handful of hydropower plants on the Naryn River (see EDM, January 15). Last December, President Atambayev said that Moscow’s financial problems had precluded any progress and that his country would hence be looking for a new investor (Fergananews.com, January 20). Still, the biggest setback may come from reduced trade with China, which remains Kyrgyzstan’s strategic economic partner. Bishkek’s accession to a shared customs territory, alongside Kazakhstan’s membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO), which provides the Kazakhstani market with more direct access to Chinese exports, could potentially disrupt trade flows from China and thereby leave thousands of ordinary Kyrgyzstanis without jobs.