Makhachkala Experiences First Special Operation in Five Years

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 47

By:

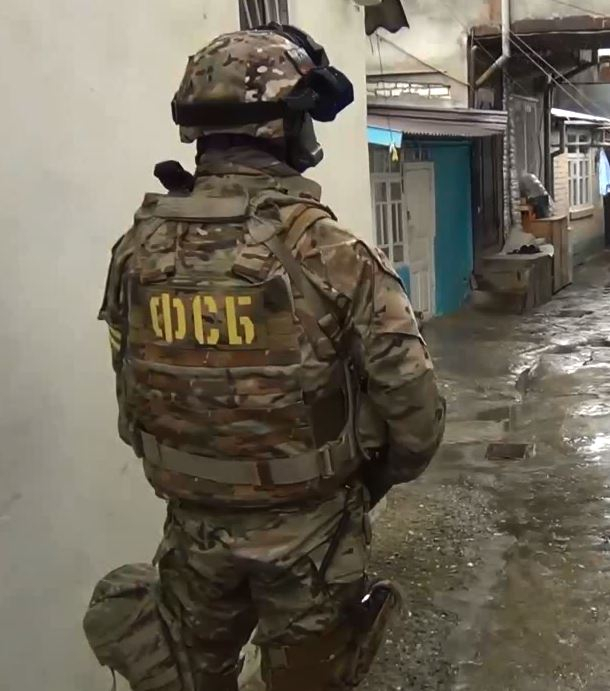

On March 11, government forces in Makhachkala, Dagestan, killed a suspected rebel. According to official sources, the suspect had been plotting a terrorist attack on government agencies. Reportedly, the authorities found a machine gun, ammunition and an improvised explosive device (IED) at the site of the man’s killing. Visual materials provided by the Russian National Antiterrorist Committee indicate that the man was surrounded in a communal living area in the Dagestani capital. The official statement also informed that the suspect was previously convicted of terrorism-related crimes. Allegedly, he was killed after firing shots at the government agents (Nac.gov.ru, March 11).

To carry out the special operation, the authorities introduced a so-called counter-terrorism operation regime in a central area of the city (Chernovik, March 11). Some media outlets pointed out this was the first counter-terrorism operation regime in Makhachkala since 2016. The identity of the suspect was not officially released, but according to some reports, he was a 56-year-old man and, in the past, served 17 years in prison on terrorism-related charges. His sentence was commuted on the grounds of poor health (Kavkazsky Uzel, March 13). For a person convicted of terrorism to be released from a Russian prison on poor health grounds, he or she must truly be critically ill. It is unclear what threat to society this individual posed. Given the low regard for law among the Russian security services, the suspect may have been killed simply because government agents considered him to be a threat a priori (see EDM, February 4).

Dagestan used to be an important hotspot of separatist insurgency in the North Caucasus. After the active phase of the second Russian-Chechen war was concluded with the defeat of proponents of Chechen independence, most of the violent deaths related to the insurgency took place in this easternmost regional republic, peaking in 2010–2011. A sharp almost three-fold drop in violence levels occurred in Dagestan as recently as 2017. Lately, the numbers of recorded victims of violence have been in the single digits (Kavkazsky Uzel). The initial plunge coincided with the appointment of Vladimir Vasiliev as the acting governor of Dagestan in 2017. Vasiliev, who had a background in the Russian interior ministry, became the first person of non-Dagestani origin in contemporary Russia to lead the republic. However, other factors may have also precipitated the rapid decrease in the levels of rebel violence in Dagestan. One of them was the outflow of Islamist radicals to the Middle East (Novaya Gazeta, July 28, 2015; Crisisgroup.org, March 16, 2016). The exact numbers of Dagestanis who left their country to join militants in Syria and Iraq are unknown, but estimates usually point to several thousand individuals (Kavkazsky Uzel, January 31, 2017). Despite the correlation between the outflow of radicals and the decrease in the number of attacks in the region, some low level of rebel violence continued in Dagestan.

The eventual decline of the North Caucasus insurgency can hardly be explained by the exodus of radicals alone. Moscow may additionally have been successful in disrupting the regional elites’ circles that co-existed with the rebel groups and were either unable or unwilling to crush the militants using all of the government’s might. This was achieved through a rapid succession of newly appointed regional governors and a massive increase in funding. After 2010, none of the three governors of Dagestan served a full four-year term. Unable to repair the Dagestani bureaucracy at once, Moscow instead appears to have adopted the strategy of short governor terms and massive dismissals of officials at the local level. The disruption of ruling elites in Dagestan seems to have worked to an extent. Moscow’s success was supported by a large increase in the cash flows into the republic. In 2020, Dagestan remained among the most lavishly subsidized regions of the Russian Federation (second only to annexed Crimea). The region received the equivalent of about $2 billion from Moscow, including a nearly 50 percent increase in outlays compared to 2019 (Forbes.ru, March 11).

Despite the vast increases in financial aid for Dagestan, there are some indications that it has been inefficient for the economy even if it helped to quell the insurgency (Riadergent.ru, January 27). Incidentally, the first counterterrorism operation in Makhachkala in five years took place under the tutelage of Colonel General Sergei Melikov, a career military officer with experience of fighting in Chechnya during the Russian-Chechen wars. Melikov was appointed acting governor of Dagestan in October 2020. His predecessor, Vladimir Vasiliev (also a colonel general), ended his service after two (since formal confirmation by the Dagestani parliament) or three years (since appointment by the president of Russia).

In modern Russia, as a rule, only individuals from the titular ethnic groups were allowed to lead republics in the North Caucasus. In Dagestan, leaders came either from the Avar or Dargin ethnic groups. The ethnic identity of Sergei Melikov is somewhat complex. His father was a Lezgin (another Dagestani minority), but he was born and grew up outside Dagestan. He is said to be a self-proclaimed Christian Orthodox even though Lezgins traditionally are adherents of Islam (mostly Sunni but also some Shia) (Islamnews.ru, October 6, 2020). Melikov has another connection to Dagestan, albeit somewhat tragic—his stepson Dmitry Serkov was killed in the territory in 2007. Serkov was a commander in the (since disbanded) Vityaz special forces unit (TASS, July 28, 2016). Besides, Melikov may not be completely oblivious to his ethnic roots. One indication of this is Melikov’s proposal to endow Derbent with a special status, which would mean more funding for the city (Molodyozh Dagestana, December 23, 2020). To be sure, Derbent is an ancient settlement with many unique historical artifacts, but it is also notably a regional center of Lezgins, who have traditionally lived in what is now southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan.

Does Melikov embody a more stable gubernatorial solution for Dagestan, or is he another transient figure in Moscow’s trial-and-error scheme in the troubled republic? Only time will tell. For now, pouring in resources has helped to resolve some of the pressing issues in the region. However, it is far from certain how stable this solution will be even in the short run, given the Russia’s economic woes, political rigidity and lack of reforms.