Meloni at the Helm: What Does Italy’s New Government Mean for Sino-Italian Relations?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 22

By:

Introduction

Questions about the unity of Italy’s new government on several key foreign policy issues persist, ranging from the extent of its support for Ukraine to its commitment to various European Union institutions. However, on the issue of China, the new government of Prime Minister (PM) Giorgia Meloni appears united. This bodes well for transatlantic cooperation and could spell trouble for Beijing, which not too long ago entertained ideas of using Italy as a friendly counterweight in Europe. Under Meloni, Italian foreign policy, particularly toward China, is unlikely to chart a dramatically new course. This is largely because the current government has prioritized its commitment to NATO and needs to focus on domestic issues rather than risk upsetting the international arena. While openings remain for Sino-Italian cooperation in economic terms, such cooperation will be geared toward supporting Italy’s domestic challenges and is unlikely to provide Beijing with the significant foothold that it has long hoped to gain in Europe.

Summit Signals

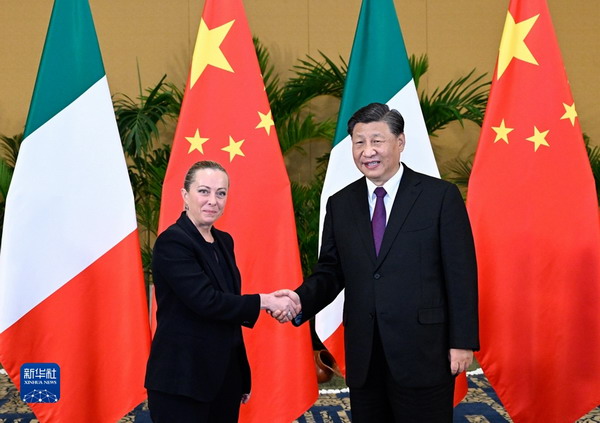

Since assuming office in October, Italy’s new prime minister has been busy. In November, she traveled to Bali, Indonesia to participate in the G20 Summit. Meloni had a cordial meeting with President Xi Jinping, which touched on issues of trade, tourism, and cultural exchange (PRC Foreign Ministry [FMRPC], November 17). Xi stressed his hope for the two sides to tap into the China-Italy Government Committee and dialogue mechanisms across sectors to explore potential cooperation in areas such as high-end manufacturing, clean energy, aviation and aerospace and in third-party markets. China is also looking to a “high-level” opening-up of ties and has announced its intention to import more quality products from Italy. Meloni accepted an invitation to visit China, while Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed his hopes that China’s relationship with Italy and the EU more broadly would not be negatively influenced by third parties, i.e., the U.S. (South China Morning Post [SCMP], November 22). However, pleasantries and promises are all well and good during such international summits; they are par for the course. Bromides about bilateral cooperation and partnership ricochet around such events just like the champagne, but their substance is open to debate.

A day after meeting so amiably with Xi, Meloni met with the leaders of Canada, India and Australia. None of these countries is particularly popular with Beijing these days. She tweeted about Italy’s “long-standing friendship and deep relationship of trade and cooperation” with Australia, the “unexpressed growth potential” of “bilateral relations” with India, and her desire to “strengthen bilateral relations” with Canada, whose prime minister, Justin Trudeau was rather roughly dressed down by Xi for putative leaks to the press (Giorgia Meloni Twitter, November 16). Notably, however, Meloni did not highlight her meeting with Xi on Twitter. It is possible to read too much into both the prime minister’s order of bilateral meetings and China’s absence from her Twitter feed, but the contrast would suggest that while Sino-Italian relations are cordial, there is no desire on the part of Meloni or her coalition to go back to the policies of the Five Star Movement.

Misplaced Hopes

Under PM Giuseppe Conte of the Five Star Movement, Italy became the first (and only) G-7 country to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (China Brief, April 24). During President Xi’s March 2019 state visit to Italy, the two countries put pen to paper on a Memorandum of Understanding to jointly advance the construction of the BRI (Xinhua, March 23, 2019). Through the agreement, Beijing hoped to deepen economic and political ties with Italy and increase its influence in Europe through Italy. For Italy, the premise behind the agreement was to leverage Chinese capital in order to improve infrastructure and trade between the two nations in an attempt to jumpstart its perennially moribund economy. Ideologically, Conte and his Five Star allies, had a neutral to positive attitude toward China, which was appreciated and shared by Beijing. Chinese state media, for example, widely disseminated Xi’s extensive response to a question from Conte about the challenges of governing China, wherein Xi discusses how he developed an attitude of “selflessness” in service of the Chinese people (CCTV, October 6, 2021).

In partnering with Beijing, however, Conte’s populist and inexperienced Five Star Movement miscalculated dramatically. Before any real progress on the partnership could be made, deteriorating U.S.-China relations, increased European skepticism about Chinese influence, and the enormous global fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic stopped the progress of the MOU in its tracks. Over time, little Chinese investment in Italy materialized. What investment there was faced opposition over fears concerning intellectual property or had been in the pipeline before the 2019 agreement. Due to COVID, trade declined dramatically. Ironically, the 2019 signing ceremony was something of a high-water mark. In the end, the much-touted partnership brought criticism of the Conte government domestically and internationally and delivered little in practical economic benefit.

Course Correction

Conte left office in February 2021, pushed out after a no-confidence vote due to disagreements over his handling of a number of economic issues, including the country’s COVID-19 recovery program. He was replaced by the former head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, who quickly and decisively pushed back against his predecessor’s flirtation with China. He made use of these “golden powers” numerous times, blocking, for example, the sale of a majority stake in a major Italian semiconductor company, LPE, to a Chinese investment company (Asia Financial, April 10, 2021). During the first half of 2022, Draghi also expanded the capacity of the government to manage the takeover of key Italian sectors by foreign corporations, further shielding Italian industry and intellectual property from Chinese acquisitions (Decode 39, April 19).

While praised by many world leaders for his pragmatic and Atlanticist approach, Draghi’s domestic position was always tenuous. Without the support of a political party, the new prime minister’s status as a technocratic leader was always going to have a short lifespan within the fractious world of Italian politics. The election that followed his resignation brought Meloni to power as part of a coalition of right and center-right parties.

Superficially, Meloni is the antithesis of Draghi. She is 45; he is 75. She is a populist; he is a technocrat. She put “country” at the heart of her campaign slogan-“God, country, and family,” while he spent most of his career with international organizations, the World Bank and the European Central Bank. Draghi, an academic, an economist, a banker, and a civil servant, was foreign to politics. Meloni began her political career at age 15 and was elected to parliament at 29.In spite of these glaring differences, there are similarities between the two leaders. On the international front, Meloni’s instincts, like Draghi’s lean toward the West. Like Draghi, she is not pro-China. Although she campaigned as an “outsider,” Meloni has a long pedigree of deep involvement in traditional Italian politics. Acknowledging the dual challenge that Russia and China pose to the current international system, Meloni openly declared that, under her government, Italy would not be “the weak link” in the Western alliance (Italian Post, October 20).

In the context of discussing the Russia-Ukraine war, Meloni’s measured statements about using politics and diplomacy to avoid military conflict over Taiwan was met with predictable criticism from Beijing. But Meloni has gone further, meeting with Taiwan’s representative in Italy, tweeting about standing “alongside those who believe in the values of freedom and democracy,” and voicing her desire to deepen cooperation between Italy and Taiwan across a number of sectors, from tourism to semi-conductors (Focus Taiwan, September 23; Giorgia Meloni Twitter, July 26). She has criticized the 2019 MOU with China and said that, at present, she would see no need to renew it (Taipei Times, September 27).

Meloni’s critical line toward China is reflected in the composition of her cabinet, which has expressed fears of developing a dependence on China. Deputy PM Matteo Salvini recently tweeted his opposition to European proposals to outlaw petrol, diesel and methane on the continent from 2035 on, saying that it was “a gift to China,” which would close factories and shops in Italy and Europe, deprive workers of wages and create a “dependence on China for life” (Matteo Salvini Twitter, October 28). Adolfo Urso, the new minister for economic development, criticized the German government for allowing China’s COSCO to buy a stake in Hamburg’s port. Urso argued that his government would work to avoid replacing dependence on Russian energy with “technological or to some extent commercial dependence on China” (The Bl, October 31) Urso’s comments neatly encapsulate the attitude of the Italian government in the post-Ukraine war world. His refusal to deliver “Italy into the hands of the Chinese,” is also significant.

While these statements of the new Italian government’s intent in the international arena are important, they do not represent the most significant challenge facing Meloni. Her party came to power as candidates of change in a country that faces numerous domestic challenges. Domestic challenges: high energy prices, high unemployment, budget deficits, low economic growth, migration, and unlocking the EU’s COVID aid and economic recovery package are what brought Meloni to power and they are what will likely preoccupy her time in office. Such domestic issues can be exacerbated by international conditions and China can exert some influence on these issues in Italy, but it is unlikely that China’s influence alone will be decisive.

Conclusion

Painfully aware of the way energy, trade, and technology can be used as political leverage, the new Italian government, like governments around the world, is taking a cautious approach to its interaction with China. On the one hand, China has an enormous market and is also a potential source of much needed capital. However, at the same time, Beijing has demonstrated how it can use trade and commercial connections as leverage. China’s recent spat and economic sanctions targeting Lithuania provide a vivid demonstration of how China is willing to leverage its economic heft as a political tool (China Brief, January 28).

Perhaps from those examples and from the experience of the war in Ukraine, European political leaders have learned important lessons that will shape their policies, at least over the short term. In the meantime, the durability of Meloni’s coalition is by no means secure. Although critical of the bureaucracy in Brussels, she remains committed to the values of democracy, freedom and political plurality. She has also expressed robust and unwavering support for transatlantic relations.

In the short term, this signals that Italian foreign policy is likely to distance itself from China and to reassert its position at the heart of Europe and the Western alliance. China will have to look for new partners in the EU to influence European politics and is likely to do so. Given the tenuous position of Europe’s economy, there will undoubtedly be interested suitors, but for now, at least, they will not be in Rome.

Andrew R. Novo is Professor of Strategic Studies at the National Defense University’s College of International Security Affairs and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. A scholar of strategic studies and the history of the Eastern Mediterranean, Dr. Novo is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. His most recent books are The EOKA Cause: Nationalism and the Failure of Cypriot Enosis (2021) and Restoring Thucydides: Testing Familiar Lessons and Deriving New Ones (2020) with Dr. Jay Parker.