MOLDOVA’S PRESIDENT KREMLIN VISIT DOES NOT UNFREEZE RELATIONS

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 3 Issue: 155

By:

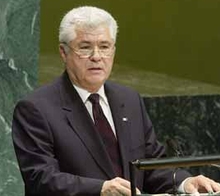

Presidents Vladimir Putin of Russia and Vladimir Voronin of Moldova met in the Kremlin on August 8, following Voronin’s repeated requests for a bilateral meeting over the past year. Other than the group meetings at Commonwealth of Independent States summits, Voronin had not met with Putin bilaterally since February 2003. Russia froze the relations after Voronin rejected the November 2003 Kozak Memorandum on Moldova’s “federalization” under Russian “guarantees” and reoriented Moldova’s policy westward.

Chisinau has tried hard to “unfreeze” the relations all along, particularly since Russia began hitting hard at Moldova’s economy for political reasons — a reality that Voronin diplomatically avoids acknowledging publicly. In their public accounts of the Kremlin visit, Voronin and his aides just as diplomatically suggest that the visit has achieved the goal of “unfreezing” the relationship. This is not the case, however. Voronin could perhaps easily unfreeze the relationship through political concessions to Moscow on Transnistria and other issues. However, he stood his ground: firmly on some issues, adroitly on others.

Voronin and his influential aide Mark Tkachuk presented to Putin a proposal for withdrawal of Russian troops from Moldova’s territory. Under this concept, Moldova would issue a flattering statement on Russia’s “peacekeeping” operation and declare that it has completely achieved its goals; the troops would withdraw with full honors; an international mission of observers, part military and part civilian, would seamlessly replace Russia’s troops; Moldova would grant “broad autonomy” to Transnistria, consistent with European standards of autonomy for regions within states.

Transnistria’s status would be worked out based on Moldova’s July 22, 2005, organic law on the principles of conflict resolution, Voronin insisted. That law stipulates that withdrawal of Russian troops, demobilization of Transnistria-flagged armed formations, and democratization of Transnistria are the goals of any political settlement. It further envisages solely “internal guarantees” — to be legislated distinctly — of the political settlement and Transnistria’s status, rather than the external “guarantees” that Russia wants to impose and enforce.

As a major incentive to Russia to go along, Voronin offered that Moldova would remain permanently neutral and/or would not host foreign forces and bases on its territory. Moldova’s constitution already stipulates the country’s neutrality and bans the stationing of foreign troops and bases — a major legal argument in Chisinau’s efforts to rid the country of Russian troops. However, Voronin tentatively played a NATO card by suggesting that Putin should be interested in the replacement of Russian troops with international observers; for the alternative would have to involve peacekeeping by soldiers “from NATO countries.”

Putin eagerly took on board the neutrality offer, but countered with Moscow’s own, familiar positions on conflict resolution. Those same positions were also aired on August 7 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ chief spokesman, Mikhail Kamynin, and again on August 9 by the special envoy for CIS affairs and conflict resolution, Valery Kenyaykin, following his talks with the European Union’s special representative to the negotiations on Transnistria, Adriaan Jacobovits de Szeged. The Russian side continues to insist that “the parties” Chisinau and Tiraspol should negotiate directly and co-equally toward a mutually acceptable settlement; the settlement must be based on documents previously worked out by the “mediators” and “guarantors” — that is, the various “federalization” and related documents developed by Russia and the OSCE from 1997 through 2005; and the settlement must be “reliably guaranteed” — code word for Russian political and military “guarantees,” directly or indirectly envisaged by those documents.

Moldova’s already pauper economy is taking heavy hits from Russia’s politically motivated embargoes on Moldova’s main exports: on fruit, vegetables, and other products since spring 2005, and on wines since spring 2006. In addition, Gazprom has doubled the price of gas in a six-month period — from $80 per 1,000 cubic meters through December 2005 to $110 in January-June 2006 and to $160 for June-December 2006, with a possible further hike on January 1, 2007.

Voronin sought relief from Putin on these measures. The only result is a promise to upgrade the negotiations on these issues from the inter-departmental level to that of the inter-governmental Commission on Trade and Economic Cooperation, which has not held a plenary meeting since 2004, but which Putin now promises to reactivate.

In sum, it takes two to “unfreeze” a relationship.

(Moldpres, Interfax, RIA-Novosti, Kommersant, August 7-9)