Moscow and Tokyo Come No Closer to Burying the Hatchet

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 183

By:

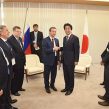

Despite Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s hopeful meeting, on October 4, with Russian Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich, as well as Abe’s talks with President Vladimir Putin, at the United Nations, the week before (Kyodo, October 6), no prospect for normalizing Russo-Japanese relations currently exists. During August–September 2015, denunciations by the Japanese and Russian governments of each other’s actions regarding the disputed Kurile Islands were an almost daily occurrence. Indeed, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs infuriated the Japanese government by saying at one point that the problem of the Kurile Islands—which the Soviet Union occupied during World War II and never returned to Japan—does not exist (Sputnik News, September 4). Moreover, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, a known provocateur, stated that if Japanese officials were real men, they would follow tradition and commit hara-kiri (ritual suicide) and calm down rather than loudly protest Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s August 22 visit to the islands (Kyodo, August 25). Clearly, high-ranking Russian authorities believe they have license to publicly and crudely insult Japan with impunity.

Russian military overflights and probes of Japan’s defenses also continue without any apparent letup. And instances of Japan having to scramble its jets to meet those probes has reached Cold War levels—increasing 700 percent since 2005 (Kyodo, September 11).

Nevertheless, in mid-September 2015, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida traveled to Moscow, where he relayed Tokyo’s willingness to host Putin sometime in the future and resume the bilateral Russian-Japanese dialogue on normalization. Japan also resumed discussions with Russia regarding trade in pharmaceuticals, farming and energy projects (Asahi Shimbun, September 16; Japan Times, September 11).

Russian analysts assessed these outcomes as proof that Prime Minister Abe’s office triumphed over the “diehard” anti-Russian faction in the Japanese foreign ministry and that dialogue had been restored (a Russian desire) at the deputy prime minister level. Moreover, according to these analysts, the meeting of the trade and economic intergovernmental commission, accompanied by ten major Japanese industrialists, shows that gradually, “in defiance of sanctions, economic interests are getting the upper hand over politics.” Andrei Fesyun, a senior lecturer at the Oriental Studies Department of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, in Moscow, went so far as to argue that the bilateral territorial dispute is apparently becoming purely an ideological issue. And he added that Moscow prevailed in relaunching the discussion on more important issues—for example, on Japanese trade and investment in Russia (TASS, Russia Direct, September 23). However, Fesyun’s may be a minority view.

Russian analysts, and presumably the Russian government, believe Russia has ultimately prevailed over Japan and that Tokyo needs these normalization talks more than Moscow does. Indeed, they apparently see Japan as significantly isolated regionally and open to any and all negotiations. Therefore Russia’s tighter stance over the Kurile Islands, overflights and truculent tone cost it nothing.

Japan’s persistent chasing after Russia probably adds to the likelihood of another failed effort at normalization. It will reinforce Russian preconceptions that Japan needs Russia more than Russia needs Japan, even though the truth is arguably the exact opposite (see EDM, July 31). It will also reinforce the probably mistaken Russian belief that it can pressure and insult Japan with impunity and still achieve its objectives. Indeed, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told Kishida during their September meeting that progress on normalization was only possible if Japan first recognized “historical realities” regarding the Kurile Islands (Asahi Shimbun, September 16).

It may also be the case that Moscow is intimating it will not even negotiate on the islands if sanctions remain in place. Putin reportedly warned Abe that if he comes to Japan, the Russian president must have concrete economic results to show for it (Nikkei Asian Review, September 15). Similarly Sergei Naryshkin, the speaker of the State Duma and a close aide to Putin, has stated that “Japan’s imposition of sanctions on Russia [passed by the West in response to the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine] has become an obstacle to bilateral relations” (Kyodo, Japan Times, September 11). Moscow may want to drive a wedge between Japan and the West by encouraging unilateral Japanese softening of its sanctions—which are already milder than those of Europe. This would also create a precedent of turning a blind eye to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine as well as potentially open up the Senkakus to Chinese claims and threats. Moreover, such a concession by Tokyo might not even garner any benefits for Japan regarding the Kurile Islands or ties with Russia.

Beyond those considerations, Japanese commentary seems to be torn between thinking that Russia is employing psychological pressure to intimidate Japan as a negotiating tactic, versus simply treating Japan with contempt. Inadvertently, however, Japan is perhaps setting itself up for further insults or coercion. Reportedly, Abe’s government sent the Kremlin a message explaining that Tokyo had already given a detailed explanation to US President Barack Obama regarding Putin’s possible visit to Japan. The communique may have been intended to display Prime Minister Abe’s determination to invite President Putin in the near future; but apparently, Putin took this message as a sign that Tokyo always checks first with Washington before acting, and so is not a fully independent international actor. Therefore, “Russia does not need to deal with Japan on an equal footing” (Nikkei Asian Review, September 15). Alternatively, this may convince Putin that Tokyo will not yield on sanctions unless Washington approves, so it is pointless for him to deal with Japan on this issue and, thus, he should just deal directly with Obama—over Abe’s head.

In any case, the Abe-Putin meeting in New York was predictable. Both men spoke in veiled terms so as not to disrupt the bonhomie: Abe cautioned against new provocations on the Kurile Islands, while Putin emphasized the need for increasing economic cooperation, which would naturally undermine sanctions (Kyodo, Japan Times, October 1; Sputnik News, September 29; Asahi Shimbun, September 29). While this performance may have been characterized by smiles and handshakes, it is difficult to see how Japan and Russia can achieve their objectives without burdensome costs. Putin probably cannot give up the Kuriles without major economic compensation, but Abe cannot offer such remuneration, due to alliance commitments and because Japanese businesses remain rightly mistrustful of Russia. On this basis, even if Putin visits Tokyo in 2016, a final normalization of Russo-Japanese relations will still be highly unlikely.