Moscow Tries to Rescue Syria from Its Own Crimes

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 104

By:

Syria has been a long-term friend of Russia during the past fifty years. Throughout this time, Moscow has sold the country weapons, supported its diplomatic posture in the Arab-Israeli struggle and has never publicly said one word about the fact that Syria is a bloody despotism ruled by a minority family and sect that is determined to hold power at, what appears to be, any cost. The outbreak of what amounts to be a civil war in Syria as a result of the Arab revolutions of 2011 has therefore put Moscow in a quandary.

On the one hand, Moscow cannot publicly approve of the widespread murder of Syrian protesters that is occurring on a regular basis. Therefore, it has, so it says, repeatedly counseled Syria to introduce modest reforms from above to head-off the revolutionary fervor and to prevent foreign intervention (www.rt.com, April 6; Interfax, www.mid.ru, May 13). On the other hand, Russia strongly opposes any UN or external intervention in what it considers to be Syria’s internal affairs. Indeed, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov accused Syrian demonstrators of seeking to attract Western intervention in Syria (www.mid.ru May 13). Meanwhile, other Russian diplomats also accuse the opposition of using violence (Xinhuanet, April 27).

Moscow’s reasons are similar to its opposition to NATO’s operation in Libya. A NATO success would ratchet up further pressure at home and abroad against other Russian friends, particularly Syria and to a lesser degree Iran. According to Russia’s Deputy Ambassador to the UN, Alexander Pankin, “The main thing in our view, is that the current situation in Syria, despite an increase in tension and confrontation, does not present a threat to international peace and security. One cannot disregard the fact that the violence does not all originate from one side. A real threat to regional security, in our view, could arise from outside interference in Syria’s domestic situation, including attempts to push ready-made solutions or taking of sides” (Xinhuanet, April 27).

Already Moscow is trying to prevent the UN from stigmatizing the Assad regime in Syria, and is urging Assad to make reforms that would keep him in power rather than simply resorting to force, which further incites Western opposition and increases pressure for a strong unilateral Western response within or beyond the UN against Syria. Since Syria is a long-term client and major arms buyer for Russia, Assad’s brutality and the consequent rise in Western pressure potentially undermine another Russian partner. These further the process of unilateral US and Western consolidation of the Middle East (potentially under democratic auspices) that would spill over into Russian territories. For the same reason, Moscow has also urged that the Yemeni and Libyan regimes make concessions and reforms in order to prevent the escalation of violence there that could trigger another comparable Western response (www.mid.ru, May 13).

A final reason for Russian opposition to intervention lies in the fact that Russia has consistently tried to restrict US use of force (not its own) to conditions whereby Washington must seek permission at the UN Security Council where Russia has a veto. This consistent invocation of the UN as the supreme arbiter of the use of force for the United States has been a systematic plank in Russian foreign policy for over a decade. Were the United States and/or NATO to demonstrate that they did not need this sanction (which Russia, if not China, would undoubtedly veto) this too would display Washington’s effective and even successful disregard for Russia’s importance to the world, with a corresponding blow to Russia’s status, prestige and real influence in the Middle East and beyond. Therefore continuation or worse, extension and prolongation, of this operation would only confirm Russian fears that Washington and NATO are unpredictable actors who are not bound by consideration of Russian interests, international law, or anything other than their own sense of their values and interests. Quite inexplicably to Russian leaders, these values and interests are often indistinguishable and an unnecessary complexity in the conduct of relations with the West. Russia, like China, clearly would like to conduct a “values-free” foreign policy with the United States and Europe in the manner of eighteenth or nineteenth century cabinet diplomacy.

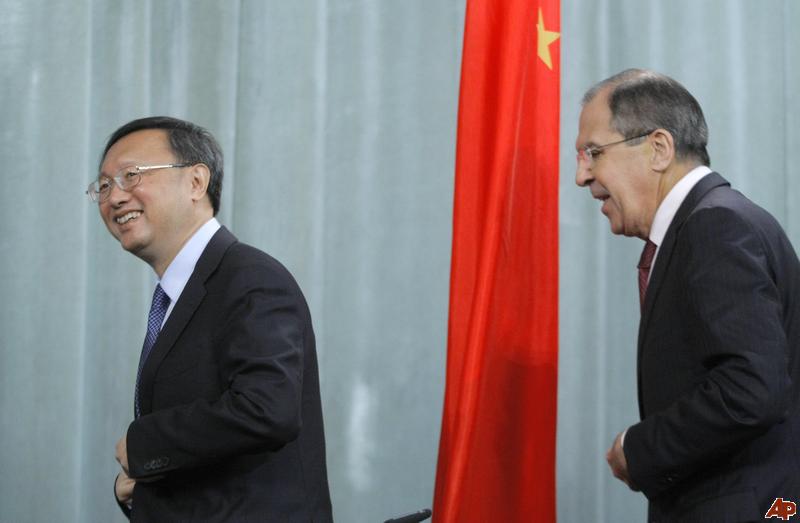

As a result, all these considerations came together when Lavrov met Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi in Moscow on May 6. The two sides announced not only their grave concern over events in the Middle East, but that they would also now coordinate actions to bring about a “speedy stabilization” of the situation and prevent negative unpredictable consequences. Specifically they adhere to the principle that peoples should be free to arrange their affairs as they see fit without outside interference. They both see the UN Contact Group as having grossly overstepped its authority –now being in favor of a NATO ground operation– thus usurping the Security Council’s formal role. They called for a peaceful settlement and no foreign intervention, which means Gadaffi wins and stays in power in Libya (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation www.mid.ru, May 6). Likewise, both sides collaborated to block a UN Security Council Resolution condemning Syria on April 29 (www.rt.com, April 29).

This Russo-Chinese coordination will also undoubtedly spread to questions concerning reform in Central Asia. More importantly, it will solidify both states’ continuing opposition to US and NATO policy and democracy promotion, and cast a long shadow over the continuation of the Obama administration’s reset policy. Those have become the real international stakes in the Arab revolution.