Myth and Reality in Russia’s Asian Policy

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 115

By:

According to Russian analysts and leaders like Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, Russia has turned to Asia because of Western sanctions and is making steady progress there in achieving its objectives (RT, June 11). However, such talk is entirely unfounded. If anything, Russian relations with Japan have worsened, and there is little sign that Moscow is being taken seriously in Southeast Asia as a truly Asian power. Meanwhile, as evidence of Russia falling into an ever greater one-sided dependence upon China continues to mount, Moscow struggles to preserve its independence as a serious Asian player in the face of Beijing’s expanding power. In fact, Medvedev and his colleagues know full well that Russia’s “pivot” to Asia began in 2008, when he was president. And that eastward reorientation was being heralded in Moscow as a major policy project at the time. Admittedly, more recent Western sanctions have accelerated and deepened that “pivot,” largely because Asian states are much more reluctant to impose sanctions. But there are few signs of great progress for Russia’s regional diplomacy outside of North Korea—and that may not be much to brag about, even for Moscow.

Japan’s initial reluctance to impose heavy sanctions is and was well known. In the end, however, Japan had no choice but to do so (see EDM, August 5, 2014). And this was despite the ongoing efforts between Tokyo and Moscow, since 2012–2013, to effectuate a rapprochement and the possible normalization of bilateral relations, which would have led to a resolution of the long-standing Kuril Islands/Northern Territories dispute (see EDM, October 15, 2012; February 24, 2014). Japan, as late as June 12, 2015, was still announcing its readiness to welcome President Vladimir Putin for an official visit later this year (Sputnik, June 12). As many commentators have long noted, both governments obviously share concerns about China’s aggressive policies. But nothing has come of these shared interests so far.

Meanwhile, on June 9, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced in Vladivostok that Moscow would accelerate the military buildup of its forces on the Kuril Islands, thus precluding any hope of progress on this issue and effectively nullifying any prospect of a sorely needed bilateral rapprochement (The Japan Times, The Moscow Times, June 9; Russia Beyond the Headlines, June 11). It is difficult to see how or what Russia gains from this treatment of Japan, particularly since the Russian Air Force already habitually flies dozens of overflights a year above Japanese territory. Even if this Russian military buildup aims as much at China as it does Japan, its timing is undoubtedly insulting to Tokyo. Bilateral normalization, therefore, looks to be buried for now, and Russia itself loses even more because it is left alone with China—although this may actually have been Shoigu and his political allies’ original objective considering that they came out, in November 2014, in favor of Russia establishing a collective security agreement with China in Asia (Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, November 18, 2014; Nezavisimaya Gazeta Online, November 20, 2014).

In Southeast Asia’s case, the recent Shangri-La Conference was an occasion for Russia’s spokesman, Deputy Defense Minister Anatoly Antonov, to denounce what he claimed were Washington’s efforts to sponsor color revolutions and the enlargement of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Ukraine. He also accused the United States of being responsible for the problems related to the South China Sea and missile defense in Asia. These charges are not only mendacious but also likely irrelevant to Southeast Asian states, which Moscow is cultivating. They demonstrate Moscow’s continued failures to make itself a useful partner to Southeast Asian and East Asian players. Moreover, Russia appears afraid to challenge China regionally and thus increasingly risks being seen in the region as China’s ally and junior partner (Carnegie Moscow Center, June 1). Furthermore, although Russia announced its intention to conduct naval exercises in the South China Sea in 2016 with friendly countries like Brunei, it also revealed its intention to conduct such exercises with China (Sputnik, May 30; Defence.pk, June 12). This only serves to signal Southeast Asia that Russia will not challenge Chinese encroachments there. And it will certainly not preclude Vietnam and other US allies and partners in Asia from forming their own coalitions to defend their interests in the South China Sea against Beijing without Moscow. So again, Russia gains little or nothing but continues to lose standing and credibility.

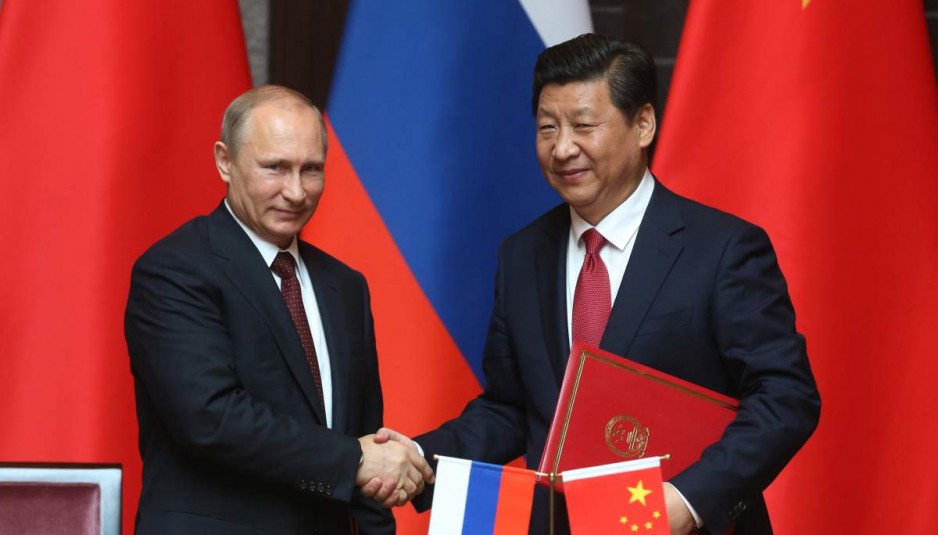

Finally with regard to China, there are growing indications of increasing Chinese demands and Russia’s subordination to them. Russian financial authorities, energy companies and state-controlled banks are stepping up their use of China’s yuan currency as Western sanctions spur diversification away from the US dollar. These include Gazprom, Gazporomneft and Sberbank (The Moscow Times, June 15). It is entirely unclear how strengthening the yuan could benefit Russia. In addition, Russian papers have now revealed that China has opened negotiations to buy ten parcels of land in Eastern Russia; the first one, in Trans-Baikal, is about the size of Los Angeles, and China is insisting on settling large numbers of Chinese workers there (Inosmi.ru, June 13; Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 15). Nothing could be more conducive to strike at Russia’s neuralgic fear of a vast influx of Chinese migrants taking away Siberia and the Russian Far East. And such examples increasingly demonstrate that Russia is, in fact, becoming China’s junior partner and being treated by China much as Beijing treats other countries it is trying to subordinate.

Therefore, it may yet turn out to be the supreme irony that a regime whose mantra is the sovereign independence of Russia, and whose purpose is to secure recognition of Russia as an independent great power in Asia, is achieving the role of a tributary to China by dint of its relentless parallel pursuit of this objective in Europe. Will Russia accept subordination to China as the price for holding on to Crimea? And will this give it what it seeks in Asia?