NATO and Georgia: Beyond the Open Door

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 101

By:

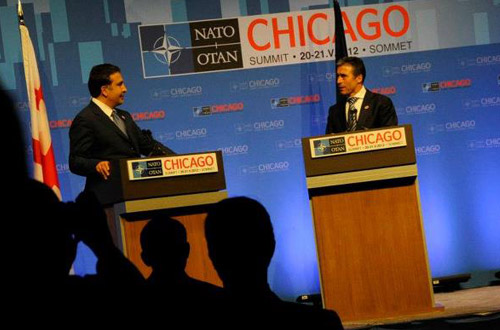

NATO’s summit on May 20 in Chicago has brought Georgia slightly closer to the “open door” of membership in the Alliance. The Chicago summit’s declaration reaffirms earlier decisions, committing NATO to positive consideration of Georgia’s membership aspirations. The Chicago document reads: “At the 2008 Bucharest Summit we [had] agreed that Georgia will become a member of NATO and we reaffirm all elements of that [and] subsequent decisions. We welcome Georgia’s progress since the Bucharest Summit to meet its Euro-Atlantic aspirations” (NATO Summit Declaration, Chicago, May 20).

The 2008 Bucharest decision – the starting point of Georgia’s road toward accession – read: “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. […] A Membership Action Plan [MAP] is the next step for Ukraine and Georgia on their direct way to membership” (NATO Summit Declaration, Bucharest, April 4, 2008).

However, Germany almost single-handedly vetoed a Georgian MAP at that Bucharest summit and (with some like-minded countries) discouraged re-consideration of the issue in NATO to date. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian government no longer aspires to join the Alliance, having instead re-committed Ukraine to non-bloc status. The German and Ukrainian governments, each in its own way are deferring to Russia in their respective decisions on these issues.

Georgia, de-coupled from Ukraine, is now linked with the Balkan countries aspiring to NATO membership. At the Chicago summit, NATO satisfied Georgia’s request to be grouped officially with the three Balkan aspirant countries. This move equates Georgia with the countries of Southeastern Europe, whose accession to the Alliance seems pre-determined, although the time-frame depends on their performance in meeting the standards.

Underscoring this positive change, NATO held a meeting of the 28 member countries with the four aspirant countries – Georgia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina – at the Chicago summit. Keynoting that meeting, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared, “the United States remains deeply committed to the open door policy, and we will keep working with each of them, both bilaterally and through NATO, to help them implement finally the reforms needed to meet the standards for membership.” Reviewing the aspirant countries’ efforts, Clinton placed Georgia at the top of this class (US State Department press release, May 21).

The United States basically set the tone on Georgia at the Chicago summit. For its part, Germany tried again to lay obstacles into Georgia’s path to NATO’s open door. At the insistence of a German-led group of countries, the Chicago Declaration reaffirmed “all elements” of the Bucharest and subsequent decisions (see above). This seemingly cryptic reference backs up Berlin’s duplicitous position: on one hand, stipulating that MAP is an obligatory stage for Georgia to pass before membership; and on the other hand, rejecting year after year a Georgian MAP. With such tactics, Berlin is inverting MAP’s nature, turning it from a path toward NATO membership (proven during three consecutive enlargement rounds) into its opposite, a tool for blocking that path.

Georgia’s supporters had resisted the “all elements” reference in the run-up to Chicago, but could not block it. The US, some other supporters of Georgia in NATO, and Tbilisi itself take the position that MAP must not be deemed indispensable or obligatory. However desirable in itself, MAP can be substituted by the existing, NATO-approved mechanisms: NATO-Georgia Commission and Annual National Plan (ANP), both operating since 2008. Although initially designed as a partial consolation for the MAP denial, the Commission and ANP can be upgraded to fulfill MAP’s functions in promoting inter-operability and conducting performance reviews.

Thus, NATO’s Chicago summit acknowledged: “The NATO-Georgia Commission and Georgia’s Annual National Program have a central role in supervising the process set in hand at the Bucharest Summit. We welcome Georgia’s progress since the Bucharest Summit to meet its Euro-Atlantic aspirations through its reforms, implementation of its Annual National Program, and active political engagement with the Alliance in the NATO-Georgia Commission. In that context, we have agreed to enhance Georgia’s connectivity with the Alliance, including by further strengthening our political dialogue, practical cooperation, and interoperability with Georgia” (NATO Summit Declaration, Chicago, May 20).

The language could have been more convincing, but the German-led group ruled out any mention of Georgian membership prospects in connection with the NATO-Georgia Commission and ANP. It was also Berlin who blocked the holding of a session of the NATO-Georgia Commission at the Chicago summit. According to the German government, NATO should have held such an event in parallel with a NATO-Russia meeting, if Russian President Vladimir Putin had deigned to attend NATO’s Chicago summit. Absent Putin, however, the German-led group – mostly consisting of NATO under-performers – forced a postponement of the NATO-Georgia Commission meeting.

Such obstructions, however, look like mere rearguard attempts to slow down Georgia’s advance toward NATO’s open door. If NATO maintains the integrity of its Open Door policy, with membership prospects dependent on performance only, and Georgia outperforming the other aspirants, Georgia cannot for long be kept waiting in front of that open door.