Nazarbayev Blocks Russian TV in Kazakhstan

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 2

By:

In slightly over a generation, Kazakhstan has gone from being a republic in which ethnic Russians formed a plurality, to one in which ethnic Kazakhs form a two-thirds majority. But to keep that country within Russia’s orbit, Moscow still counts on the fact that most urban Kazakhs speak Russian rather than Kazakh. Nonetheless, linguistic patterns in Kazakhstan are changing: Ever more Kazakhs are speaking their native tongue as well as foreign languages other than Russian. And ever more ethnic Russians in Kazakhstan are left with the choice of learning the national language or emigrating to Russia. Together, those linguistic and demographic shifts are changing Astana’s political and geopolitical position.

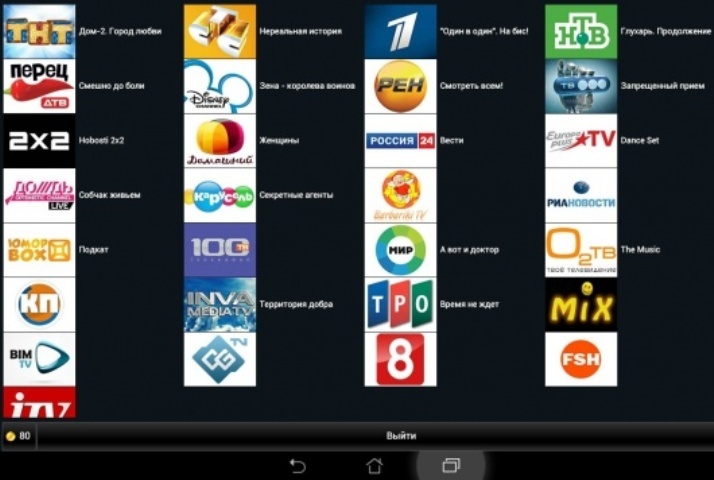

A new Kazakhstani law, which went into effect on January 1, 2016, has thrown these changes into sharp relief. Nominally intended to protect domestic advertisers, the measure has the effect of banning Russian (and the few other non-Kazakhstani) channels from cable networks in the country. Such channels could meet the law’s requirements by editing out all advertising. But doing so would mean that the owners would lose some or all of their profits and would need subsidies from Moscow to continue, subsidies that—in the current economic environment—the Russian government may not be able or willing to give (Asiarussia.ru, December 27, 2015).

About 75 percent of Kazakhstan’s population, including virtually all ethnic Russians and a majority of urban Kazakhs, watch Russian-language television. Therefore, the end of these broadcasts will inevitably lead some to focus on Kazakh-language programming instead. And because this reflects President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s long-standing commitment to advance the use of the national language in Kazakhstan, most citizens of this Central Asian republic will view the new law as an indication of how they should behave.

Kazakhstani political analyst Avdos Sarym, who has examined this situation, says that steps like this mean that in another decade, anyone who wants to advance in Kazakhstan will have to speak both Kazakh and Russian, rather than assume he or she can behave as in Soviet times and manage with the Russian language alone. Such a mental shift will deprive President Vladimir Putin of yet another segment of what he defines as “the Russian world” (Matritca.kz, November 28, 2015).

Most ethnic Russians in Kazakhstan even now speak only Russian, Sarym points out. If they know a second language, it is far more likely to be English than Kazakh. But “the absolute majority of Kazakhs speak both Kazakh and Russian, and an increasing share of the young speak English and Turkish. That general pattern, however, obscures the fact that the Russian-speaking segment of the population, which includes both Russians and Ukrainians, has split over the war in Ukraine and does not form “one and the same social and political stratum” in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan’s Ukrainians and Russians have no “common values and markers,” although they may have “common fears,” Sarym argues (Matritca.kz, November 28, 2015).

“The main problem” in Kazakhstan today, he continues, is that Kazakhstani society “does not have even one idea commonly recognized by the majority. In essence, today, we have two ideas, which only rarely intersect, one of which [the Soviet Russian] is declining in size while the other [the Kazakh] is unceasingly growing.” The situation is changing rapidly in favor of the latter, Sarym says; the country will eventually be “Kazakh and Kazakh-speaking.” And “it would be good if this Kazakh and Kazakh-speaking society mastered as well not only Russian but also English, Turkish, Chinese and other languages” (Matritca.kz, November 28, 2015).

That increasingly presents special challenges to those who, today, speak only Russian. “It is no secret,” he continues, “that many of our fellow citizens still think Kazakhs are limited and that the possibilities of the Kazakh language and education are limited as well.” But that is simply wrong, although it is, in fact, sustained by the current educational system. “If the current system of ignoring the Kazakh language in the school is retained, then in a short time, Russian and Slavic youth will have a choice: to be uncompetitive in the labor market in Kazakhstan or to be ready to migrate.”

The shifting balance between Russian and Kazakh is already being registered in those businesses that depend on people aged 20 to 45. In that age group, Kazakh speakers predominate, and in younger cohorts, they are even more dominant. Almost 80 percent of those entering school now are ethnic Kazakhs, and they are the future customers and investors. Today, the average age of ethnic Kazakhs in Kazakhstan is 26–27; that of the Slavic residents of the country—46–47. Kazakh may not be the language of all the business community now, but it soon will be.

Another trend that matters, Sarym says, is that Kazakhs, historically a rural population—in 1986, only 3 percent of the residents of Almaty were Kazakh—are moving into the cities. In the past, that meant Sovietization and Russification, but in the future, it will surely become the basis for the formation of an urban Kazakh identity. Kazakhstani cities have not yet become “Kazakh-friendly.” But if they do not become this soon, Sarym argues, there could be “collisions and problems”—not so much for the Kazakhs who, as a result of their numbers, will simply overwhelm the cities, but for the others who will find themselves embattled minorities waiting to leave.