Nuclear Security and Arms Control Are Non-Issues for Russia

Nuclear Security and Arms Control Are Non-Issues for Russia

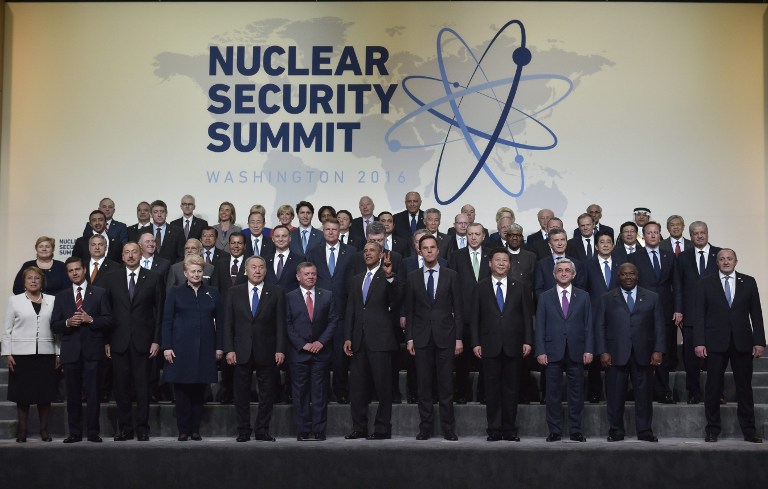

Russia’s absence from the nuclear summit in Washington, DC, last week was entirely predictable and yet baffling. Moscow announced its non-participation last November, and Secretary of State John Kerry was unable, in recent lengthy talks, to persuade President Vladimir Putin to make a trip to the United States’ capital (Newsru.com, March 31). The Kremlin was irked by the description of its behavior by US officials as “self-isolation” but could not invent a convincing explanation for why it was boycotting the high-profile event attended by more than 50 world leaders (Kommersant, March 30). The official statements emphasized the “deficit of cooperation” in the US-organized summit, and Putin perhaps believes that Russia should have been accorded some entitled special status by virtue of being the world’s second-largest nuclear power, on par with the US. Alexei Arbatov, one of the leading Russian experts in nuclear arms control, argues that the demonstrative refusal to partake betrays a fear in the Kremlin of showing any weakness, which overrides any obvious interest in enhancing Russia’s and the world’s nuclear security (Carnegie.ru, March 30).

Moscow commentators sought to establish that without Russia the Washington summit was a disappointment (Gazeta.ru, April 1). It was indeed unusual for a state that attaches so much importance to upholding its nuclear profile to refuse to engage in discussions on crucial matters of global security, particularly from the threat of terrorism, which looms large for Russia (Novaya Gazeta, April 1). At the same time, Putin’s pronounced emphasis on modernizing Russian nuclear capabilities and gaining political advantage from demonstrating this might mean that his government has nothing to contribute to the debates aimed at reducing the nuclear menace (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, April 1). The disagreements between Moscow and Washington over possible Russian violations of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and modernization of US nuclear bombs deployed in Europe are far from intractable, but they fit into the broader context of diverging nuclear philosophies (Kommersant, March 11; Vedomosti, March 31). President Barack Obama remains firmly committed to further proposed cuts in the strategic arsenals; Putin is set on making Russia’s upgraded nuclear weapons into usable instruments of policy (Rbc.ru, April 2).

This pro-nuclear stance puts Russia in conflict not only with the US but also such key allies as Kazakhstan and India and, in fact, with the majority of the world—with the obvious exception of North Korea (Ezhednevny Zhurnal, March 31). It was, therefore, essential for the mainstream Russian media to emphasize the intensity of disagreements in various bilateral meetings on the fringes of the Washington summit. The talks between Obama and China’s President Xi Jinping were presented as failing to bridge the differences in positions on the status of the South China Sea, illustrated by a recent visit of a US naval squadron to the contentious Spratly archipelago (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, March 30). Tensions in exchanges between Obama and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan were illuminated, primarily because tensions in Russia-Turkey relations show no slackening (Moskovsky Komsomolets, March 29). Prime attention was given to Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko and his meetings and speeches in Washington, which were portrayed as viciously anti-Russian and far from successful (Rossiiskaya Gazeta, March 31).

The crisis in relations with Ukraine indeed continues to be a major drawback for Russia’s international status, even if Russians themselves are now significantly less concerned about it compared with their acute domestic economic problems (Levada.ru, March 28). The ceasefire in Donbas is violated by daily heavy gun battles. And after visiting the Ukrainian trenches and checking the readiness of the troops, Poroshenko presented in Washington irrefutable facts and figures on the Russian occupation of the eastern parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (Newsru.com, March 28). At the same time, a new plan for granting the rebel-held enclave a special status is now being considered by the Ukrainian parliament, in order to deny Russia an opportunity to exploit the pretext of the non-implementation of the Minsk agreements (Gazeta.ru, March 30). What has inflicted severe damage to Russia’s political maneuvering around the deadlocked conflict is the shameful trial of Ukrainian soldier and politician Nadezhda Savchenko, who this week will be sent to a prison camp to start serving her 22-year sentence (Grani.ru, March 25). Putin drags his feet on the decision to exchange her for two Russian Spetsnaz (special forces) soldiers captured in Ukraine, suspecting that it might look like a loss of face under international pressure.

Instead of properly dealing with any of the above-mentioned issues, the Kremlin was preoccupied with an “information attack” in the Western media directed specifically at Putin (Forbes.ru, April 1). The substance of this “attack”—which the Kremlin pre-emptively dismissed as defamation organized by foreign special services—amounted to revelations in the media of several luxury apartments given as presents to Putin’s daughter, two relatives of his alleged girlfriend, and a young lady who advertised herself as a hot fan of Russia’s leader (Kommersant, April 1). By Russian standards of corruption, this investigation is unlikely to go far, but the nervousness of Putin’s subordinates could only have been generated by a severe angst of their boss (Moscow Echo, April 1). Coming to Washington with personal worries of this sort was, thus, really not an option for Putin.

The four nuclear security summits will certainly constitute an important part of Obama’s presidential legacy, and Putin is clearly reluctant to contribute to this achievement in advancing the vision of a nuclear-free world. First of all, Putin’s own world-view—of a strife-ridden world, in which Russia alone can check the encroachments of the inherently hostile West by resorting to nuclear deterrence—is strikingly different. But second of all, Putin represents an aging autocrat compared to Obama—a younger leader, who is preparing to step down from the position of supreme power, while still expecting to be able to have a good life afterwards. For the Russian president, there is no after; and though his power may appear absolute, the declining economy has revealed its limits, leading to the build-up of an invisible but irreducible discontent. Putin appears to live in fear of a day when distant noise may start rising beyond the Kremlin walls while the internal corridors become quiet and empty. It is difficult to know what might trigger this meltdown of the monolith of bureaucratic control, so every revelation of petty self-indulgence causes panic in the Putinist system. The nuclear button gives an illusion of security, but at the end of the day, it is just the most dangerous of vanities.