Party Ties: Vietnam, Cuba and China’s Relations with Other Marxist-Leninist States

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 9

By:

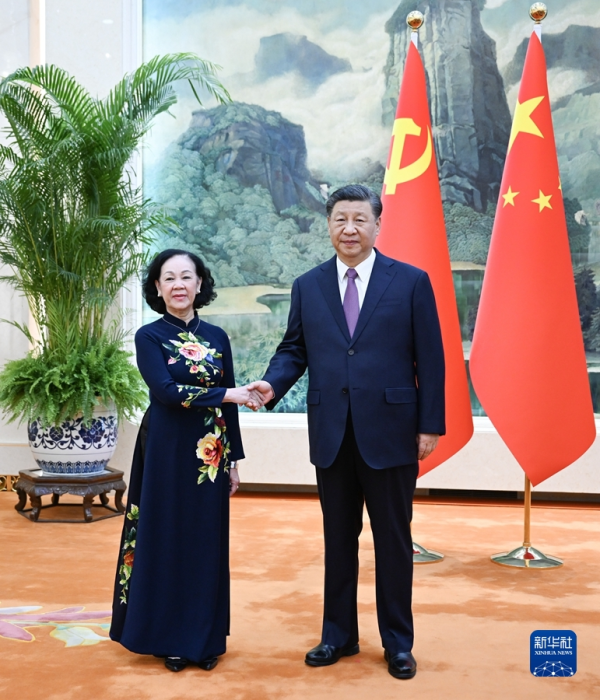

Last month, on the 15th anniversary of the establishment of the China-Vietnam comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership (中越全面战略合作伙伴关系), Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping met with Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) Politburo Member and Head of the Central Committee Organization Commission Truong Thi Mai and asked her to convey his greetings to General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong (People’s Republic of China Ministry of Foreign Affairs [FMPRC], April 26). [1] The visit to Beijing by Mai, who has headed the VCP’s powerful organization commission since 2021 and was appointed to the Secretariat in March, occurred days after U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Vietnam (NhanDan, April 15; VN Express, March 6). As the maritime dispute between China and Vietnam in the South China Sea has intensified over the past fifteen years, Washington has deepened its ties with Hanoi based on overlapping geostrategic interests. Nevertheless, the Biden administration’s ability to achieve its goal of upgrading the U.S. relationship with Vietnam to a “strategic partnership” this year to mark the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the U.S.-Vietnam “comprehensive partnership” remains in question (Fulcrum.sg, April 20).

Vietnam undoubtedly perceives the PRC’s drive to consolidate control over the South China Sea as its main geopolitical challenge. Moreover, Vietnam’s relationship with its larger northern neighbor is colored by mistrust derived from historical memories of Chinese occupation and a long legacy of conflict, including the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War and the subsequent series of border and naval clashes in the 1980s. However, the VCP, particularly the conservative faction, now views the U.S. as posing its primary ideological threat and is fearful that Washington aims to undermine its grip on power (Nikkei Asia, May 11, 2022). As two scholars at Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences note in a recent analysis, Hanoi’s reluctance to upgrade ties with the U.S. stems not only from fear of angering China but also from concern with “Washington’s excessive focus on press freedom, religious freedom, and human rights as an internal intrusion and potential threat to Vietnam’s political security.” [2] Hence, Beijing is able to arrest Hanoi from drifting towards closer alignment with Washington by leveraging their shared Communist systems and mutual concerns about Western efforts to facilitate the “peaceful evolution” of communist states into liberal democracies.

During his meeting with VCP General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong in Beijing last October, Xi spoke to both Party leaderships’ mutual concern with regime security. He stressed that each side “should stay committed to the socialist orientation” and called for increased party-party exchanges to facilitate “mutual learning in party governance and state administration, maintain high-level communication and strategic dialogue between the two militaries, achieve more outcomes in cooperation on law enforcement and security, and safeguard the political security and social stability of respective countries” (FMPRC, October 31). Party-to-party ties are a key element of the PRC’s relationships with the other three states with ruling Communist Parties: Vietnam, Cuba and Laos. [3] As with the CCP, the Vietnamese, Cuban and Laotian Communist Parties have each adapted and modified Marxist-Leninism to suit their national conditions, regional situations and elite political preferences. Despite their considerable differences, these states’ mutual Marxist-Leninist ideological orientations and systems foster shared interests, including maintaining regime security and “stability,” opposing perceived external attempts to define and impose Western conceptions of democracy and human rights, advancing a state-led model of economic development and promoting a more multipolar world.

“Comrades and Brothers”

The ideological comity between the CCP and the VCP was underscored when General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong led the first foreign delegation to visit China following Xi’s attainment of a third term as Communist Party chief at the 20th Party Congress in late October (CCTV, October 31, 2022). During Trong’s visit, the two sides released a “Joint Statement on Further Strengthening and Deepening China-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership.” In the statement, both sides agreed that their “traditional friendship as ‘comrades and brothers’ (同志加兄弟), which was forged and carefully cultivated by Chairman Mao Zedong, Chairman Ho Chi Minh and other older generation leaders is the precious inheritance of the two peoples,” which must be maintained and advanced (People’s Daily, November 2, 2022).

In the joint statement, both parties pledged unswerving adherence to Communist Party leadership based on the path of socialism that best suits their respective national circumstances. They also pledged to intensify party-to-party cooperation by continuing to implement the five-year (2021-2025) CCP-VCP cooperation and cadre training plans to hold joint theory seminars and strengthen exchanges between party members at all levels. Notably, the joint statement includes not only a pledge to strengthen defense cooperation and exchanges, but also calls for strengthening cooperation to enhance political security, including through leveraging mechanisms to resist “color revolution” and “peaceful evolution.”

Inter-party exchanges between the CCP and the VCP on Marxist theory, party building and good governance practices are regularly held at the national, provincial and some local levels, particularly in border areas such as Guangxi and Yunnan, according to Xu Liping, director of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Center of Southeast Asian Studies (Guancha, November 1, 2022). Xu noted that as both countries are implementing policies of “reform and opening,” they face many common challenges and stated that Vietnam can learn from China’s success in combining communism and traditional Chinese culture so that Marxism can better take hold in the country. He stressed that these exchanges foster “self-confidence” in both the Communist system and theory. Xu also stated that large numbers of VCP officials will come to China to attend the Central Party School and selected local Party Schools for cadre training in order to learn from China’s experience in socialist governance.

While General Secretaries Xi and Truong have both re-emphasized Marxist-Leninist ideology during their tenures, they have also each launched anti-corruption campaigns to root out graft and strengthen their respective holds on power. Consequently, one area where there has been extensive inter-party exchange between the CCP and the VCP is anti-corruption coordination, enforcement and training. For example, in September 2021, the heads of each party’s respective central anti-graft bodies, then Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) chief Zhao Leji and VCP Central Inspection Commission head Trần Cẩm Tú held a video conference with other top party officials to review their experiences countering corruption (Nhan Dan, September 6, 2021). In an example of the role that subnational, provincial disciplinary commissions also play in such exchanges, in May 2019, Liu Xuexin, who was then Secretary of the Fujian Commission for Discipline Inspection Commission, met with the head of the Vietnamese Discipline Inspection and Supervision Cadre Training Course to exchange views on anti-corruption enforcement, interdicting fugitives and recovering stolen goods (Sohu, May 28, 2019).

Like Xi, Troung was able to orchestrate a third term as party head and on his watch, a number of senior officials, including former ministers, several of whom favored closer ties with the U.S., have been expelled from the party ranks. His biggest powerplay came in January, when President Nguyen Xuan Phuc, widely seen as a supporter of closer relations with the West, was compelled to step down amidst a string of recent corruption scandals (DW, January 17). Phuc’s exit, along with Troung’s overall tightening of political control, plays into the PRC’s favor by stalling and even threatening to reverse, the recent deepening of U.S.-Vietnam ties.

The Cuban Connection

On the other side of the world, mutual enmity toward the U.S. and a common Marxist-Leninist orientation, have fostered close relations between China and Cuba. The Caribbean nation enjoys the unique designation in the PRC’s lexicon of foreign relations as “good friend, comrade and brother” (好朋友、好同志、好兄弟) a relationship Xi hailed as “standing the tests of time” in his congratulatory call with then Cuban Communist Party First Secretary Raul Castro on the 60th anniversary of the establishment of official relations (CCTV, September 28, 2020). Of course, PRC-Cuba relations have ebbed and flowed since 1960, far more than Xi acknowledged. The two countries enjoyed affable but distant relations in the period after Fidel Castro’s revolutionary regime made Cuba the first country in the Western Hemisphere to recognize the PRC. However, the relationship cooled during the 1970s and early 1980s, when the Sino-Soviet split was at its most intractable.

As a staunch Soviet ally, Cuba mostly aligned with the Soviets in conflicts for influence in the developing world, which often put it at odds with the PRC. During the Angolan Civil War, Cuba deployed troops in support of the Soviet-backed MPLA, whereas the PRC, along with the U.S. and South Africa, backed the FNLA and later the UNITA, (U.S. Department of State). However, the collapse of the Soviet Union, along with the continued overall U.S. isolation of Cuba, precipitated a major warming of relations between Beijing and Havana.

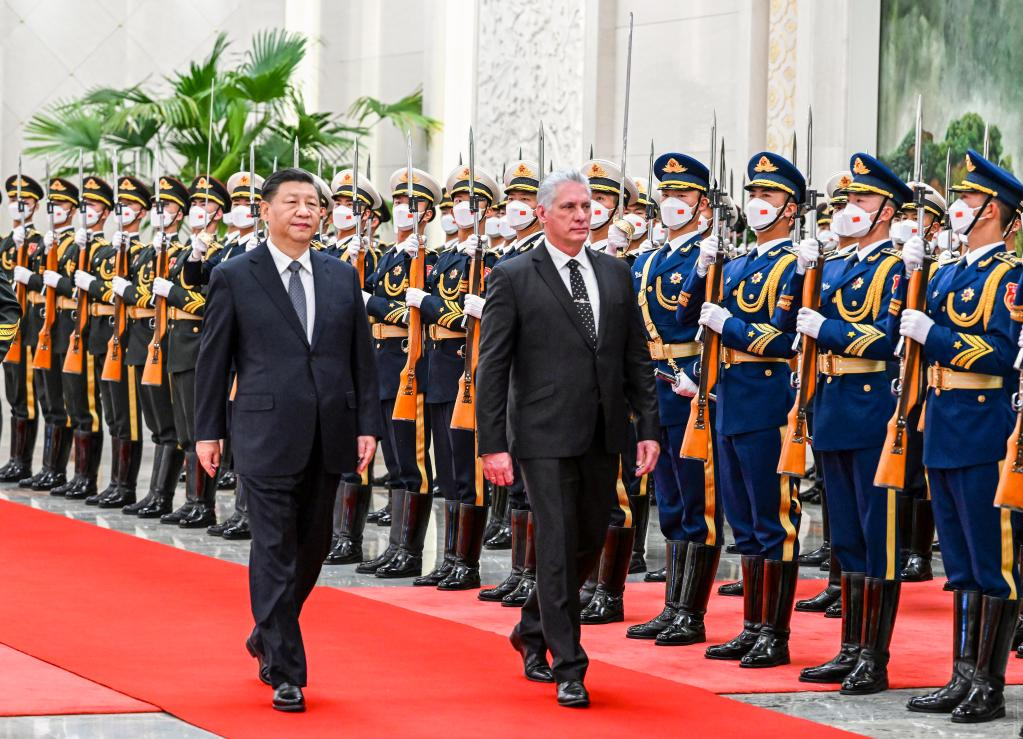

In late November, Cuban Communist Party Secretary Miguel Díaz-Canel made a state visit to China, becoming the first leader from Latin America and the Caribbean to visit Beijing after the 20th Party Congress. In his meeting with Díaz-Canel, Xi stressed that the PRC accords Cuba a “special position in its diplomacy” and stressed that no matter how the international situation evolves, China will unswervingly “support Cuba in the path of socialism,” “defend international fairness and justice” and resolutely oppose “hegemony in world politics” (Xinhuanet, November 25, 2022). As Cuba’s economy has struggled recently due to the impact of the global pandemic, excess debt and the destruction caused by Hurricane Ian last year, Havana has looked to the PRC for a lifeline. During Díaz-Canel’s state visit to Beijing, the PRC agreed to restructure Cuban debt and extend $100 million in hurricane relief assistance (SCMP, November 27, 2022).

Conclusion

A common Marxist-Leninist orientation, mutual support for the “socialist cause” (社会主义事业) and shared concern about Western-orchestrated regime change, provide a normative framework for the PRC’s relationships with Vietnam and Cuba (Gov.cn, August 30, 2021). However, both relationships also carry strategic, diplomatic, and in Vietnam’s case, economic importance, for Beijing.

Beijing is undoubtedly aware that the continuance of a Communist government in Havana precludes the full normalization of U.S.-Cuba relations and allows the PRC to occupy a position as Cuba’s main external ally. As regards Vietnam, the shared ideological orientation is equally critical to maintaining a workable relationship despite the major dispute over the South China Sea. Once seemingly in decline, the VCP’s concern over U.S. political interference appears to be on the rebound, which plays into Beijing’s hands. Thus far, Hanoi has managed to balance its ideological comity with Beijing and its geopolitical synchronicity with Washington. However, the PRC can succeed in shifting Vietnam’s focus from geopolitics to regime security, it could arrest and possibly even reverse the growing strategic cooperation between the U.S. and Vietnam.

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Notwithstanding the specific titles applied to the PRC’s relationships with a handful of key partners (e.g., Russia and Pakistan) a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership” is generally considered the highest official designation in the PRC’s hierarchy of strategic partnerships (see SCMP, January 20, 2016).

[2] Huynh Tam Sang and Vo Thi Thuy An, “Is a US-Vietnam Strategic Partnership Likely to Happen Soon?” The Diplomat, April 21, 2023.

[3] Although the Korean Workers Party in North Korea originated as a Marxist-Leninist Party and retains many elements of Communism, the party’s official ideology is Juche, which since 2012 has been derived solely on the bases of Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism and hence falls outside the scope of this article, see Hisashi Hirai, “Comrade Kim Jong-un’s revolutionary thought,” Japan Institute of International Affairs, February 20, 2023.