PLA Theater Joint Intelligence: Organization and Operations

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 5

By:

China’s new theater command structure represents a major advancement in building a streamlined joint command structure. One key remaining bottleneck is intelligence sharing. Accurate and timely intelligence is always a key component of any successful military operation, and especially so for the advanced joint operations the PLA envisions. Skilled intelligence and technical personnel, and joint command and coordination regulations are required to support the intelligence process, as well as direct intelligence operations at subordinate echelons. As the PLA attempts to build an advanced joint operations capability, rapid collection, accurate analysis and dissemination of actionable intelligence is critical to support precision command, maneuver, and fire strikes with situational awareness, targeting and battle damage assessments. The PLA’s current stove-piped intelligence system requires continued modernization including automated systems to assist analysis and dissemination, improved and expanded reconnaissance assets, and integrated communications for sharing intelligence.

Theater Joint Command

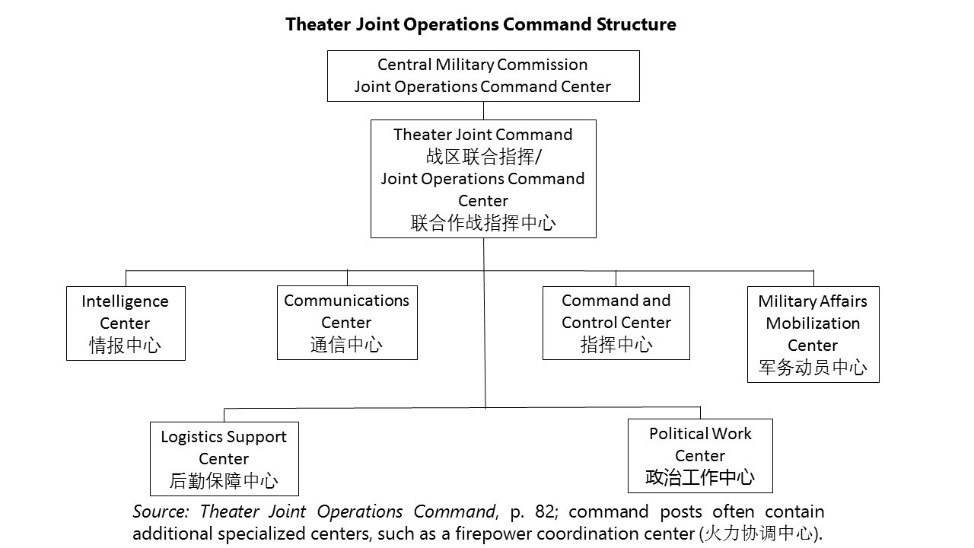

The new Theater Joint Commands’ Joint Operations Command Centers (JOCC—联合作战指挥中心) contain intelligence centers, as do command posts (CP) formed at each echelon down to regiment level. [1]

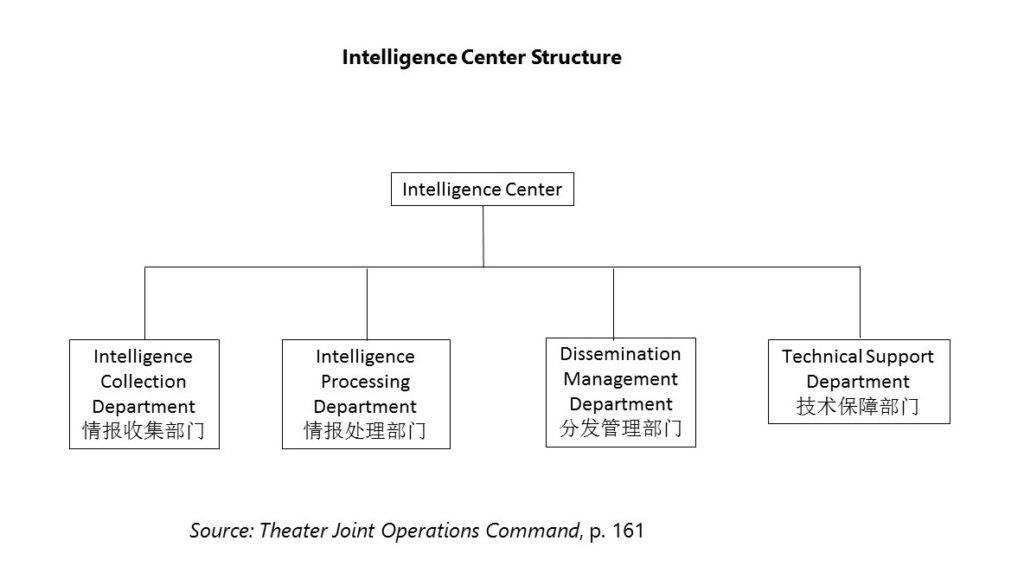

The internal theater command structure, as well as the intelligence center organization are not uniform and vary as dictated by the special circumstances facing each command. Under the supervision of the theater joint command’s chief of staff, the joint intelligence center consists of intelligence staff officers from the services, the Strategic Support Force and technical staff. [2] This center is responsible for preparing the joint reconnaissance plan (联合侦察计划) to support the theater’s command and control center and operational forces. The joint intelligence center plays a coordinating role to lower level intelligence centers and subordinate reconnaissance forces. The center is responsible for, coordinating theater reconnaissance operations, centralized intelligence fusion, as well as coordinating with the Central Military Commission’s (CMC) JOCC, national intelligence agencies and the Strategic Support Force. [3] The theater command’s intelligence center can establish subordinate intelligence centers, for example, ground, air and maritime. These subordinate centers would maintain service-specific situation maps feeding into the joint intelligence center’s current battlefield situation map (战场通用态势图) providing a common operating picture to all forces. The theater command’s intelligence center disseminates reports to intelligence centers at lower echelons supporting subordinate forces, as well as coordinate with other theaters’ centers. [4]

The intelligence centers of various operational groups (作战集团) or campaign formations (军团) conducting the theater operations and other theater subordinate reconnaissance assets transmit intelligence to the theater joint intelligence center, as well as the theater command and control center. The theater intelligence center has directly subordinate technical reconnaissance, special reconnaissance and other units collecting intelligence. The theater joint intelligence center provides guidance to subordinate reconnaissance assets based on the joint reconnaissance plan. The theater intelligence center can request space, network, and electromagnetic battlefield reconnaissance support from the Strategic Support Force, and additional intelligence support from the CMC’s JOCC, as well as support from national intelligence agencies. [6]

PLA assessments note that current intel transmission and dissemination is slow, especially in a joint environment. Improvements in the intelligence system include a transition to a flatter network structure that is intended to break barriers between services and branches. Collection, analysis, and dissemination of actionable battlefield intelligence, are being standardized and automated to speed up the processing and dissemination of intelligence. This is further enhanced through the creation of intelligence databases that can be queried. [10]

Planning

Planning and organization of intelligence is crucial to support operations. The theater chief of staff supervises and manages the development of the joint reconnaissance plan, and submits the plan for the joint commander’s approval. The theater command and control center provides the joint intelligence center with the intelligence requirements supporting the operational plan. The requirements can vary from one operational phase to another. The joint reconnaissance plan assigns missions to reconnaissance assets, plans missions to support various operational phases, prioritizes collection against the most urgent requirements, establishes coordination and support methods, and assigns timelines for completing tasks. Reconnaissance assets are concentrated along the main operational direction, with assets and missions adjusted as operations progress or as the situation changes. Reconnaissance operations could be increased in other regions to deceive the opponent as to the actual main direction. [11]

Intelligence Collection

According to the PLA, joint operations require extensive intelligence collection on political, economic, and military issues that can impact operations. The PLA places importance on peacetime collection, including the use of “tourists” and open sources, as wartime collection becomes restricted. Comprehensive peacetime collection can support rapid intelligence production to support an unexpected crisis. Units at each echelon down to battalion level have subordinate forces to conduct reconnaissance in their area of operations. This intelligence is shared with neighboring and subordinate units, as well as reported up the command chain. Subordinate commands can request intelligence support from superior headquarters, and intelligence centers are required to coordinate closely with counterparts in neighboring units to share relevant intelligence. Intelligence centers coordinate with the People’s Armed Police, militia, and local authorities during a conflict on mainland China. In overseas conflicts, in addition to national and PLA reconnaissance assets, intelligence will come from “underground party organizations,” agents, fellow travelers, prisoners of war, and captured enemy documents and equipment. The fishing fleet and civilian ships also provide valuable information. [12]

The eventual goal is to achieve a “full-dimensional” 24/7 all-weather intelligence collection capability. Theater intelligence includes satellite, aircraft, maritime, ground, electromagnetic and network reconnaissance assets. The PLA considers reconnaissance satellites an important theater intelligence means to provide long-range monitoring of ground and sea targets. Air, maritime, ground and other technical collection means are also important to present a comprehensive battlefield situation for commanders at all echelons. [13]

Intelligence Processing and Analysis

Fast-paced modern operations require rapid and accurate intelligence analysis. As the PLA adapts more complex ISR systems, the quantity of data produced is quickly outpacing analysts ability to process it. Computer-assisted processing is required for timely and accurate processing and dissemination of intelligence, however, automation levels within the PLA currently is considered low compared to advanced countries. Analysis supports updating of a digital battlefield situation map displaying a common operating picture to CPs down to the regiment level, and possibly to battalion level command vehicles. The digital display provides layered information—including operational plans; friendly and enemy force disposition; space, air, maritime and ground situation; geographic and obstacle information; meteorological and hydrographic situation; and electromagnetic environment. Combat statistical tables, text, audio, and visual information can also be available for display. [14]

The intelligence centers sort, validate and analyze collected data, producing finished intelligence. Critical intelligence is reported immediately to the commander, and emergency information is immediately distributed to units. PLA publications state that only trained personnel should evaluate and interpret intelligence data, including validating the collected information. Specialized personnel analyze technical reconnaissance such as satellite or aerial imagery, electronic collection, and enemy weapons and equipment performance. The intelligence centers will initially sort and categorize intelligence in various ways, such as subject (information on enemy forces, friendly forces, or the operational environment), time (historical, current, or future intelligence), and priority (critical, general, reference intelligence information). Intelligence evaluation and feedback is used to strengthen the relevance and quality of reporting. The PLA believes that development of automated systems will speed up the collection, processing, dissemination, and database storage and retrieval of intelligence. [15]

Dissemination

The intelligence centers use various methods to disseminate relevant intelligence to units. It is important to note that higher level commands restrict dissemination to intelligence deemed relevant to a subordinate’s combat missions to limit overloading with unneeded information. Classification levels would also limit access. Currently, these decisions are made primarily by intelligence center staff, with automated systems assisting to a greater degree in the future. Intelligence databases currently exist in the PLA, although PLA publications indicate this will increase in the future including greater flexibility for users to query databases. PLA forces use a variety of wired and wireless communication methods, and increasingly rely on BeiDou for brief, secure messages. Ultimately an integrated approach is used depending on the situation. [16]

Information Security and Intelligence Confrontation

Information security is an important aspect of intelligence and reconnaissance. These measures include not only strict control of information and systems, but also active and passive counter-reconnaissance measures including deception, terrain masking, electronic warfare and cyber offense and defense. Close coordination between the military and local governments, and strict control over civilian communications and news media are considered important in maintaining information security. Control of electronic emanations, radio silence, and technological means such as frequency hopping, spread spectrum, and burst communications are advocated. [17]

The PLA also uses the concepts of intelligence struggle (情报斗争), intelligence deception (情报欺骗), and intelligence deterrence (情报威慑) which includes deception and interference to prevent, or destroy the enemy’s intelligence collection capabilities. Intelligence deception includes spreading disinformation to confuse the enemy leading to inaccurate assessments and decisions. Intelligence deterrence is the control of intelligence or feeding false intelligence to the enemy to lead the enemy to avoid confrontation or reduce the intensity of his actions. The Strategic Support Force is likely responsible for information security and intelligence confrontation actions at the strategic level. [18]

Modernization Requirements

The PLA recognizes shortcomings in communication construction—such as automated communication networks—to meet theater joint command requirements. The PLA assesses current intelligence sharing and dissemination means as poor, requiring improved communication system integration and personnel training. The theaters rely on satellite communications for long-range communications, supported by an integrated trunk communications network as the main communications systems. China is developing quantum information technology, including a satellite communications system for high capacity, rapid and secure communications. The PLA assesses that the communications systems, for example the theater field automated communication network, require continued modernization to eventually reach the level of developed countries. An integrated, networked intelligence system is required to ensure real-time sharing of intelligence information. The PLA admits that its military reconnaissance units are not as extensive as more advanced countries, requiring greater quantity and quality. Military reconnaissance and early warning long-range capabilities are considered weak, a severe limitation for Navy and Air Force operations at greater distances, and possible expeditionary operations or support for special operations abroad. The PLA does consider its computer talent a strength to support cyber reconnaissance or computer network exploitation. [19]

PLA assessments identify technologies to support improved reconnaissance and surveillance operations. Spread spectrum communications technology provides greater security by lowering the probability of detection and interception. Detection and direction-finding technologies can, long-range battlefield reconnaissance and surveillance radars capable of detecting, locating and identifying moving ground, air and maritime targets, and passive detection systems are identified as important technologies by the PLA. Stratospheric and tropospheric balloons for early warning, reconnaissance, and communication relay are also discussed in PLA publications and advertised at arms shows. The airships can be linked with Navy vessels, AWACS aircraft, other aircraft and aerostats to create a networked reconnaissance architecture to provide greater redundancy, direction of reconnaissance operations, and comprehensive intelligence system. [20]

The current extent and quality of operational and tactical level intelligence reforms is not clear. Theater joint intelligence should eventually provide centralized intelligence fusion of service reconnaissance assets, and an entry point for strategic intelligence reporting to support theater operations. PLA press reports improvements breaking barriers allowing intelligence sharing between branches and units at the tactical level. However, tactical units are solving issues on their own, rather than high-level direction standardizing communications and the intelligence process (PLA Daily, March 3, 2015; PLA Daily, October 17, 2015). Tactical unit intelligence centers also report inundation with vast amounts of intelligence in a short time, with over 60 percent of the information worthless. Not only did the large amount of information stress the communications bandwidth, but also the ability to sort for critical intelligence. Again, units have sought their own solutions to filter intelligence. It remains unclear whether the current emphasis on high-level direction for reforms is providing standardization and uniform guidance to subordinates (PLA Daily, November 25, 2015). Tactical UAVs are allowing units to quickly conduct reconnaissance of their area of operations, overcoming difficult terrain and obstacles that would restrict reconnaissance patrol’ mobility (PLA Daily, May 3, 2016). The integrated command platform is allowing greater real-time intelligence sharing, and currently providing digital battlefield situation maps to tactical units (PLA Daily, May 11, 2016; PLA Daily, October 30, 2016).

Conclusions

Rapid and accurate intelligence collection, analysis and dissemination will require numerous improvements and modernizations to support future PLA requirements for high-tempo maneuver operations by dispersed joint forces and long-range precision strikes. The creation of a theater joint intelligence structure should lead to improved intelligence fusion. New joint command and coordination regulations are required for full implementation of the theater commands, and the PLA is working to correct the problems facing joint command and intelligence operations at all echelons. Current weaknesses include the quantity and quality of reconnaissance assets, particularly long-range capabilities, as well as integrated communications and automated systems. The PLA recognizes the dangers of information overload, and intends to increase automated systems to assist in disseminating actionable intelligence to subordinates. Future PLA intelligence operations require an integrated networked system breaking service barriers, increasing speed and efficiency transmitting time sensitive intelligence to support decision-making at all command levels. The PLA is making progress, but there is much to be accomplished.

Kevin McCauley has served as senior intelligence officer for the Soviet Union, Russia, China and Taiwan during over thirty years in the U.S. government. Mr. McCauley writes primarily on PLA and Taiwan military affairs. His publications include “PLA System of Systems Operations: Enabling Joint Operations” and “Russian Influence Campaigns against the West: From the Cold War to Putin.” @knmccauley1 tweets current Chinese, Taiwan and Russian military news.

Notes

- The theater’s JOCC acts as the main CP (基本指挥所). In addition, there would normally be an alternate CP (预备指挥所), a rear CP (后方指挥所) and possibly a forward or direction CP (前进(方向)指挥所). The alternate and rear CPs for the theaters are likely fixed and underground. The rear CP might be collated with the theaters’ Joint Logistics Support Center. Each CP would have to have an intelligence center and follow the course of operations closely in the event they need to take command operation if other CPs are destroyed or inoperative. At lower echelons, this transfer of command could occur during displacement of a CP.

- The level of expertise and experience of the intelligence centers’ staff, particularly the technical staff is not known, nor is the shift system employed to maintain 24/7 operations. It is likely that the skill levels between shifts varies in quality.

- The PLA security classifications include Top Secret (绝密), Secret (机密) and Confidential (秘密), and dissemination of classified material is based on need to know. The classification levels available to various echelons is not known for the PLA, but would restrict dissemination of intelligence. It is likely that the PLA also has code word and compartmented classifications.

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 82–83, 123 and 158–161

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) p. 161, 156-158.

- Command Information System Course of Study, (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013) p. 23

- Command Information System Course of Study, (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013) p. 27

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 116-118

- Precision Operations Command, Shijiazhuang Army Command College, (Beijing: PLA Press, 2009) pp. 107–112

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 168–169; Precision Operations, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2011) pp. 141–142; Military Terms, (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2011) p. 219

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 170–172; Precision Operations, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2011) pp. 136–137

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 122–123

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 119, 123 and 166

- Precision Operations, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2011) pp. 145-146; Joint Operations Command Organ Work Course of Study, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2008) pp. 72–75; com, November 17, 2014

- Precision Operations, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2011) pp. 144–145

- Precision Operations, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2011) pp. 140–141 and 147

- Military Terms, (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2011) p. 225

- Theater Joint Operations Command, (Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2016) pp. 125, 158–159 and 172–173

- Command Information System Course of Study, (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013) pp. 64–69 ; PLA Daily, February 24, 2017; China Daily, January 19, 2017