Political Bickering Over Georgian Financial Regulations Highlights Weaknesses in Country’s Political Culture

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 147

By:

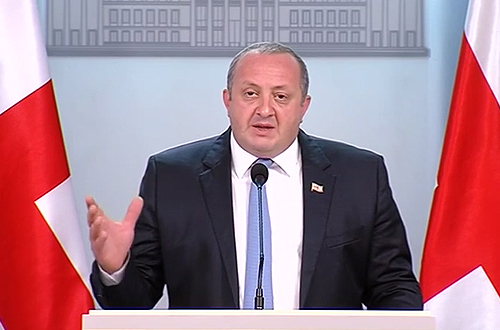

On July 31, Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili announced, with some degree of pomp and theatrical showmanship, that he was vetoing a highly controversial and widely debated bill on banking supervision (Channel 1, Maestro TV, Rustavi 2 TV, July 31). The bill, adopted by the Georgian parliament on July 17, strips the National Bank of Georgia (NBG) of its supervisory functions over the country’s financial institutions and transfers those responsibilities to a newly created body, the Financial Supervisory Agency (Civil Georgia, July 17).

The bill on banking supervision has a brief, yet quite melodramatic history. Starting roughly in November 2014, the value of the country’s domestic currency, the Georgian lari, began to fall drastically, mainly due to the strengthening of the US dollar as well as decreasing exports and remittances. Therefore, Georgia’s government began looking for someone to blame in order to appease the outraged and already impoverished Georgian public. The blame quickly fell on the NBG, which set interest rates and oversaw the country’s financial institutions, and the central bank’s chief, Giorgi Kadagidze. Although not an apt financial manager, Kadagidze had little to do with the 28 percent devaluation of the lari since last November. Aside from increased government spending, the Georgian currency was, in fact, mainly affected by outside economic factors.

Nevertheless, the ruling Georgian Dream (GD)–led coalition attacked the NBG and Kadagidze for months. This entire campaign culminated in late May with GD’s legislative initiative to introduce the above-mentioned bill on banking supervision. The introduction of the bill set in motion another round of political bickering, which looks set to dominate Georgian politics for the rest of this summer and a portion of September, when the parliament will reconvene to try (and most likely succeed) to override the president’s veto.

After its introduction, the bill was attacked and repeatedly criticized by opposition politicians, business associations and civil society members. Indeed, news coverage of the banking supervision legislation dominated Georgian TV since May (Rustavi 2, Maestro TV, May 21–August 3). As the controversy grew, President Margvelashvili made a desperate attempt to steal the show: he expressed strong opposition to the bill and repeatedly threatened to scupper this legislation with a veto. In turn, Georgian Dream swiftly went on the offensive. One member of parliament from the GD party even reminded Margvelashvili that he was elected president not because of his own political qualities, but thanks to the personal backing of Bidzina Ivanishvili (then Georgian prime minister), from whom Margvelashvili later defected (Acn.ge, July 31).

In reality, the contentious bill has little significance for the economic and political life of Georgia. Arguably, the shifting of financial supervisory functions from one agency to another cannot and will not have a substantial impact on the country’s economic outcome. This is a mere bureaucratic measure, whose importance has been blown out of proportion by both the government and opposition.

The political drama over the banking supervision bill reinforces the fact that Georgian political elites, in the government, as well as in the opposition, lack viable political ideas and programs to address the country’s real problems—its profound economic and political malaise, which create existential threats to Georgia. Rather, ideologically bankrupt political elites in Georgia are engaging in heated debates of little or no significance to justify their political existence.

At the same time, Georgian political elites seem to be confusing this ongoing political bickering with healthy democratic politics. After President Margvelashvili vetoed the banking supervision bill, Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili stated that this action was “part of a democratic process,” while somewhat paradoxically adding that the GD-dominated parliament would override the president’s veto anyway (Tabula.ge, July 31). Meanwhile, Margvelashvili optimistically declared that the “veto [was] a constitutional mechanism to promote cooperation between Parliament, President, and the Government […] and jointly give the country better solutions” (Civil Georgia, July 31). Yet, since both men came to power, they have rarely, if ever, reached a democratic, healthy compromise over any political or economic issue that the country faces (see EDM, September 18, 2014).

The problems inherent in Georgian politics cannot and will not be addressed overnight. Throughout its recent history, this South Caucasus country never really experienced a fundamental change in the political elite. In Georgia, many former Communist functionaries and their immediate offspring have held onto economic and political power and led the country, uninterrupted, since the disintegration of the Soviet Union. A portion of those elites managed to market themselves as democrats and free marketers. Yet, all too often, their declared goal of profound political and economic transformation far exceeded their capabilities, or was overshadowed by personal desires to maintain their grip on power by any means. Currently, there is a notable dearth of political talent to put forth useful solution or to meaningfully challenge the current crop of ruling elite. It remains to be seen whether, after 25 years of stagnation, Georgian society may soon wake up to the negative role the collective political classes continue to have on the country’s troubled political-economic situation.