Predicting China’s Next Foreign Minister: Key Factors and Policy Implications

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 22

By:

Introduction

At the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 20th Party Congress in late October, five diplomats were selected as full Central Committee members, one of whom will be appointed as China’s next foreign minister (FM) at the National People’s Congress (NPC) next March (Xinhuanet, October 22; China Daily, March 19, 2018). [1] The FM is responsible for executing Chinese foreign policy as laid out by the core leader. Although, the FM is usually only a Central Committee member and not on the Politburo, the position still plays an important role in the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) policy-making process. As top leaders provide only a broad, general direction for foreign policy, the foreign ministry must implement and determine policy specifics. In this process, the FM has some latitude to make modest adjustments and therefore, influence policy outcomes.

In considering the FM’s role in Chinese foreign policymaking, it is important to note that the senior-most diplomatic position in the PRC system is the Director of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission Office, a role, held by Yang Jiechi since 2013, which FM Wang Yi, who was just appointed to the new Politburo, is likely to assume (Xinhuanet, October 23). In addition to the Foreign Ministry, which is a state body under the purview of the State Council, numerous other state and party organs, including the CCP’s International Liaison Department, play a role in shaping Chinese foreign policy. Nevertheless, the Foreign Ministry is still the primary organ for foreign policy implementation through its day-to-day management of diplomacy. Consequently, as our research indicates, Chinese leaders likely value a broader range of qualifications when selecting an FM in comparison to other top ministerial-level posts. In addition to the traditional promotion criteria of age, experience and personal relations, we observe that FM candidates’ expertise, their experience serving as a vice foreign minister and the core leader’s relative pragmatism on foreign affairs, are largely unrecognized, but nevertheless important factors that impact the selection process. Based on these factors, current Deputy Director of the National Security Commission Office Liu Haixing and Chinese Ambassador to the U.S. Qin Gang are the top candidates to become China’s next foreign minister (PRC Embassy in the U.S., July 28, 2021; The Paper, March 14, 2018). The final choice will offer some key clues as to the PRC’s approach to foreign policy over the coming half-decade.

Key Selection Criteria

Ordinarily, the primary prerequisites for official promotions in the PRC are age, experience and personal relations. However, these factors alone cannot explain the turnover of senior officials in the FM role over the past several decades. For example, prior to his promotion to become FM in 1998, Tang Jiaxuan had not served abroad as an ambassador, which rendered him far less experienced than other senior diplomats (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs [FMPRC], May 28). Moreover, Wang Guangya, who was then director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, did not become the foreign minister in 2013, even though as the son-in-law of late Vice Premier Chen Yi, he was among the most prominent princelings (China Daily, September 30, 2007). The incidents highlight that there are clearly some unique qualifications for the role of FM, which differentiate it from other minister positions.

Two important, but largely overlooked factors influencing FM selection are the level of pragmatism exercised by the top leadership and the chosen official’s legitimacy. Due to the profound impact of foreign affairs on China’s interests, the supreme leader ultimately chooses the FM.

In choosing an FM, leaders first determine their foreign policy prerogatives and then select a senior diplomat who can best execute their objectives. The core leader sometimes even orchestrates broader personnel reshuffles in order to ensure their chosen candidate is politically in line to lead the foreign ministry.

As foreign affairs are vital to the PRC, top Chinese leaders must employ pragmatism, rather than unrealistic ideas, in order to avoid any accident or incident that could detrimentally affect China’s interests and its leadership’s political capital. [2] Hence, Chinese leaders are more likely to choose the most suitable and competent diplomat available to execute their foreign policy.

Maintaining workable relations with the U.S. and Japan are longstanding objectives of the PRC’s foreign policy. Both countries have a major impact on the PRC’s economic and security interests, but relations can be complicated by strong popular nationalism, which often sours Chinese public opinion toward these countries. As a result, since the start of economic reform and opening up, Beijing has sought to use diplomacy to sustain manageable relations with the U.S. and Japan. The importance of these relationships is reflected by the fact that many foreign ministers have come into the position with experience serving as Beijing’s Ambassador to either Washington or Tokyo. Such experience is valuable in enabling the FM to draw on relationships with senior American and Japanese officials, build mutual trust and develop greater understanding of these key foreign countries’ polities.

Even when the top leader has decided on their preferred candidate for FM, they still must ensure that the chosen official has the domestic legitimacy necessary to represent the foreign ministry within the bureaucracy. Consequently, successful FM candidates must also possess traditional promotion qualifications of age, experience and personal relations. As a result, ministerial-level diplomats or vice foreign ministers are prime FM candidates. The former group of officials are at the same level as the foreign minister and outrank most of the other diplomats in the foreign ministry. On the other hand, there are dozens of vice minister-level diplomats including vice ministers of other departments and some ambassadors. As vice minister-level positions in the foreign ministry are limited, some diplomats transfer to other bureaucracies in order to become minister-level officials. Such moves are often regarded as losing the competition among diplomats, making them inferior to those who still serve in the foreign ministry and, therefore, not entitled to pursue the role of FM.

As for ambassadors, their role is to boost bilateral relations, while vice foreign ministers manage multiple issues and, consequently, accumulate similar experience to that of the FM, who is responsible for overseeing the entire ministry. Accordingly, those who have served as vice foreign ministers, especially those currently at this rank, are the top candidates for the minister among all vice minister-level diplomats.

Trends in Personnel Arrangements Since 1991

Excluding the disarray in personnel arrangements before the 1990s caused by the Cultural Revolution and its aftereffects, the pragmatism of Chinese top leaders and the legitimacy of the selected official are the main factors influencing the promotion patterns of PRC FMs and other top foreign ministry officials over the past 30 years.

Due to the vital security and economic interests, Chinese leaders’ choice of new foreign ministers has been influenced by the ebbs and flows of U.S.-China and Japan-China relations. While Japan-China relations went sour due to the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands and other issues before the change of FM in 1998 and 2013, respectively, U.S.-China relations became the top priority prior to the new appointment of FM in 2003 and 2007 due to the 2001 Hainan Island incident and the 2008 Summer Olympics. It is worth noting that then top leader Hu Jintao selected a new FM in 2007, right before the 17th Party Congress. Given that it was the first time for China to hold the Olympics representing Chinese national pride and the status of a major power in the world, China’s top leader would want to avoid any diplomatic problem that could impact the event’s success. At that time, U.S. and China were dealing with some vital issues—the North Korea nuclear situation and risk of Taiwanese independence—that could easily derail bilateral relations. Consequently, at such junctures, Chinese leaders opted for a diplomat with the needed expertise as FM to manage or ease tensions in key bilateral relationships. In order to ensure that such promotions are justifiable internally, the chosen diplomat must be the most qualified among those on the shortlist. Since 1991, Tang Jiaxuan, Li Zhaoxing, Yang Jiechi and Wang Yi were appointed PRC FMs because they were the most qualified diplomats at the times of their selections (see table one).

Table One: Potential Nominees for Chinese Foreign Ministers since 1991

| Year | Name | Age | Experience | Legitimacy Concerns |

| 1997 | Xu

Dunxin |

63 | Embassy Minister to Japan | Xu was too old to be promoted to the minister level. |

| Tang

Jiaxuan |

59 | |||

| 2002 | Li

Zhaoxing |

62 | Ambassador to U.S. | Yang was too young to be the foreign minister. |

| Yang

Jiechi |

52 | |||

| 2006 | Zhou Wenzhong | 61 | Ambassador to U.S. | Yang had served as a vice minister-level official longer than the others. |

| Yang

Jiechi |

56 | |||

| Liu

Xiaoming |

50 | Embassy Minister to U.S. | ||

| 2012 | Cui

Tiankai |

60 | Ambassador to Japan | Wang was the only minister-level official among them. |

| Wang

Yi |

59 | |||

| Cheng

Yonghua |

58 |

However, except for current FM Wang Yi, none of the FM appointees were the most senior or experienced among all Chinese diplomats at the time of their appointments. However, Chinese leaders circumvented this my limiting the candidate pool to ensure the legitimacy of their promotions. For example, if the Chinese top leaders choose a FM with a relative lack of experience or seniority, such as Tang Jiaxuan in 1998 and Yang Jiechi in 2007, senior ambassadors would stay in their posts longer than average tenure and then retire.

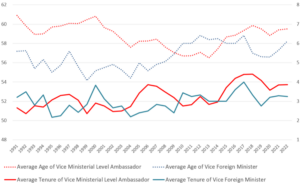

Moreover, as 62-year-old Li Zhaoxing was too old to be promoted to the minister under normal conditions, senior vice foreign ministers younger than Li were appointed as ambassadors, rendering Li a top choice in the ministry. These deliberate personnel arrangements can be observed by the irregular trend of average age and service tenure before the appointment of new FM in 1998, 2003 and 2007. For instance, the irregular personnel reshuffle involving Li is underscored by the sharp descent in the average vice minister-level ambassadors’ tenure from 2000–2003 (see Table Two).

Table Two: Average Age and Tenure of Senior Diplomats: 1991-Present [3]

In Wang Yi’s case, he was the most qualified diplomat at time of his of his promotion to the FM role. It is, however, worth noting that 61-year-old Wang Guangya, who was then director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs office—might have been 59-year-old Wang Yi’s main competitor for the role (FMPRC). Both were minister-level diplomats and prominent princelings, meaning their credentials were almost identical. However, as Wang Guangya had not served in Japan and Wang Yi had successfully defused the tension between the two countries during his tenure as ambassador in Tokyo, it is reasonable to assume that this boosted Wang Yi’s candidacy to assume the role of FM.

The Logic of Diplomatic Personnel Arrangements in the Xi Era

Although preserving China’s vital security and economic interests remains critical to the PRC’s foreign policy, Xi’s pragmatism on foreign affairs has differed from his predecessors since economic reforms got underway. In order to consolidate his political capital in an effort to convince political elites and the public of his commitment to strengthen China, Xi has emphasized protecting China’s interests and prestige through fierce diplomatic struggle. During the 4th press conference for the 20th party congress, Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu concluded that vigorously safeguarding China’s national sovereignty was Xi’s signature achievement in foreign affairs since 2012 (Xinhua, October 21).

With the abolition of Chinese presidential term limits in 2018, Xi further consolidated his power and could start enforcing his will with far less interference than in the past. At that time, Wang Yi was already 65 and would have had to retire had he not been promoted to the state councilor or another high-level state position. Since both U.S.-China and Japan-China relations remained positive in 2017, Xi could choose a diplomat with either U.S. or Japanese experience as the next foreign minister. However, Xi still needed an FM capable of crisis management because of his determination (at least ostensibly) to preserve China’s interests at all costs. Given that Wang Yi had abundant experience in crisis management, including his successful handling of Japan-China relations in his first term as foreign minister, retaining him was crucial for Xi, particularly as the international environment became more challenging for the PRC. Hence, Xi decided to let Wang have a second term as foreign minister by promoting him to the role of state councilor.

In order to justify Wang’s extended tenure, Xi studiously prolonged ambassadors’ terms and promoted diplomats with neither U.S. nor Japanese experience as vice foreign ministers. For instance, instead of choosing younger diplomats for key posts in Washington and Tokyo, both China’s Ambassador to the U.S. Cui Tiankai and Ambassador to Japan Cheng Yonghua were stationed in their respective positions for over five years, despite being too old for future consideration for promotion to FM (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA] ). Furthermore, senior Vice Foreign Minister Li Baodong and Liu Zhenmin were the ambassadors to the UN and Wang Chao, who served most of the time in the commerce ministry until his transfer to the foreign ministry in 2013, was not a career diplomat, and hence, not qualified for promotion to FM. As a result, Wang Yi was the most eligible senior diplomat to be the foreign minister then.

Even cronyism, a vital factor for promotion in the Xi era, has not applied to the appointment of the FM. While the senior diplomats serving in the office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission (CFAC) are usually regarded as Xi’s confidants, none of these officials were favored for promotion to FM in 2018. Ye Dabo, Le Yucheng, Song Tao and Kong Quan, all of whom had not been posted to U.S. or Japan as senior diplomats, served as CFAC deputies prior to 2018, (The Paper, August 24, 2018; FMPRC; Xinhua, November 26, 2015; The Paper, June 3, 2016). Even though Kong Quan and Song Tao were promoted to ministerial level positions in 2015, the former retired in 2018 and the latter did so in 2022 (Xinhua, March 16, 2018; Xinhua, June 3).

Conclusion

Based on the cases of the former Chinese foreign ministers and the global situation at the time of their selection, we posit that the level of core leadership pragmatism and FM candidates’ legitimacy are crucial to choosing China’s foreign minister.

Since 2018, U.S.-China relations have soured due to disputes over trade, technology, Taiwan and others issues, forcing China to accelerate negotiations on the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with the EU in order to ease international pressure on the Chinese economy, particularly the technology sector. Although both sides reached a consensus on CAI in late 2020, China announced sanctions on designated European countries’ officials due to their criticisms of Chinese human rights and EU sanctions against Chinese officials, which led to the CAI being halted by the EU Parliament (Xinhua, March 22, 2021; Xinhua, December 30, 2020). As the Biden administration has not ceased to treat China primarily as a strategic competitor, boosting EU-China relations may prove to be a vital task for Chinese foreign policy in Xi’s third term.

All in all, it is highly possible that loosening or even dissolving the counter-China coalition led by U.S. is Xi’s current Chinese foreign policy goal. Improving EU-China relations would be a crucial component of any such effort (FMPRC, May 28). Given the recent tendency of U.S.-China relations and the attitudes of Chinese officials, it might be impossible to improve bilateral ties dramatically, so discreetly managing possible foreign challenges and engaging with the EU to promote European neutrality in the in U.S.-China competition appear vital. Such policy objectives may explain why Wang Yi was just promoted to the Politburo following the 20th party congress as Xi still needs a highly-experienced official to coordinate departments involved in foreign policy and their implementation. While 72-year-old Yang Jiechi is the most seasoned and senior diplomat, he could not be promoted any further and will have to retire.

According to the factors of the top Chinese leader’s level of pragmatism and the FM candidates’ political legitimacy, Liu Haixing and Qin Gang have the greatest chances to become the next FM. Interestingly, Liu hs been tapped to serve as vice foreign minister, while Qin Gang could soon be transferred back to the foreign ministry from Washington as a minister-level official based on the precedent of Zhang Yesui after the 18th party congress (CNA, May 30; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC).

The final decision on who to name FM will provide key indicators on Xi’s foreign policy goals, whether they are to promote EU-China relations in order to weather a fierce geopolitical struggle with the U.S. or rather, to seek to maintain surface harmony with the U.S. Should Xi opt for the former route, Liu Haixing would be an ideal choice give his abundant experience in Europe. On the other hand, Qin Gang could be a suitable candidate for the latter goal due to his serving experience as PRC ambassador to the U.S.

Dr. Chihwei Yu is an associate professor at the Department of Public Security, Central Police University, Taiwan, ROC, and an adjunct research fellow at the Institute for National Policy Research (INPR). He earned his Ph.D. Degree from National Taiwan University. He focuses his research on international organization, China’s foreign policy, and the regional security in East Asia.

Tristan Tang is a graduate student at the Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University. He focuses his research on defense economy and China’s foreign policy.

Notes

[1] See Chihwei Yu and K. Tristan Tang, “The Chinese Diplomats to Watch After the 20th Party Congress,” The Diplomat, November 2, 2022.

[2] For the logic of Chinese pragmatism; see: 杨寿堪, “实用主义辨析,” 人民網, May 5, 2011.

[3] For the logic of Chinese vice foreign ministerial level ambassador; see “两位副外长出任大使,17位副部级大使是怎样产生的?” 公共外交网, August 21, 2021.