Putin Overplays Hand With Normandy Summit, Inadvertently Rescues Zelenskyy From the Brink (Part Two)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 126

By:

*To read Part One, please click here.

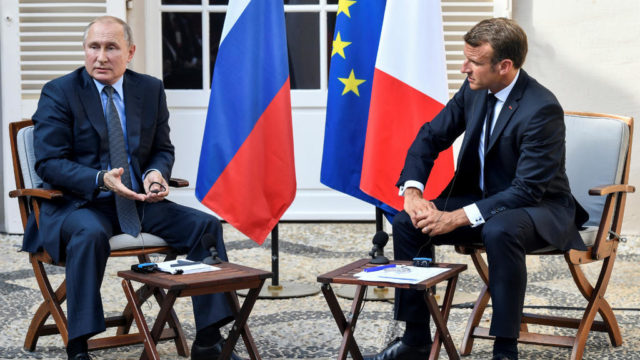

The endgame that derailed the summit of “Normandy” group leaders (Russia, Germany, France, Ukraine), planned for September 16, revealed the degree of the novice Ukrainian presidency’s readiness for concessions to Russia, as well as Russia’s all-or-nothing approach. This resulted in a quasi-ultimatum by Russian President Vladimir Putin via his adviser Yurii Ushakov, which, in turn, compromised the planned Normandy summit in Paris, where Putin hoped to enshrine the Steinmeier Formula inimical to Ukraine (see Part One).

On September 12, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy confirmed that his negotiators were, as of that moment, discussing the “Steinmeier Formula as a road map, with clear deadlines, for implementing the Minsk accords.” This was to be enshrined at the summit of “Normandy” leaders (Russia, Germany, France, Ukraine), scheduled for September 16, in Paris. Moreover, Zelenskyy called for “follow-up steps to include contact with President Putin” bilaterally, in parallel with the Normandy format (Interfax-Ukraine, Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, September 12).

In several public statements on September 13, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Vadym Pristaiko declared: Russia currently shows “a certain thaw, a warming-up“ toward Ukraine (alluding to the prisoner exchange) (Ukrinform, Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, September 13); “There is nothing treasonable, neither defeat nor victory in the Steinmeier Formula” (Interfax-Ukraine, Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, September 13); and Kyiv considers the possibility of accepting local elections in the occupied territory of Donbas as part of Ukraine’s local elections to be held country-wide in 2020 (Ukrinform, Interfax-Ukraine, September 13). According to corroborating reports, Kyiv officials did consider accepting “elections” in that territory, if Russian and proxy forces are “confined to barracks” for the duration (i.e., instead of being withdrawn or dissolved, for which there is no prospect whatsoever by 2020) (Ukrinform, September 13).

Moscow evidently took those awkward finessing attempts as prevarication by Zelenskyy’s team, and moreover as prevarication from weakness. This prompted Putin’s warning via Ushakov: the Steinmeier Formula and binding Ukrainian commitments are Russia’s preconditions to discussing a peace settlement at the summit. This last-minute intervention confirms (as do Prystaiko’s statements) that Zelenskyy’s team members had discussed these matters with Moscow and were wavering.

By the same token, the Kremlin’s warning caused Zelenskyy’s team to pull back from the brink. The Kremlin inadvertently rescued Zeleneskyy in this sense. Prystaiko went public again in the late evening of September 13 to announce that the Normandy summit was off: “Three sides were ready to meet in Paris on September 16, but the Russian side could not make it in time [sic] to the meeting. We are looking to set another date” (Ukrinform, Ukraiynska Pravda, September 13).

Backtracking statements ensued from Prystaiko after the summit’s derailment. “We are not going to introduce any special or non-special status into the constitution,” he declared, adding later that local elections in the occupied Donbas “should be held if we manage by 2020 to evacuate the troops and achieve the other [democracy-related] prerequisites” (Ukrinform, Interfax-Ukraine, September 14).

These vacillations reflect the dysfunctional nature of the Zelenskyy team’s Russia policy at this early stage in the new administration. Prystaiko, a well-respected diplomat with a distinguished record of service, is the public face of that policy. However, he is subordinate to and dependent on not only the novice president, but also on Zelenskyy’s close circle, composed of a mixture of political operatives, former business partners and film producers. They positioned their boss as the anti-war, pro-peace candidate—now president—who is supposed to deliver on those promises. Within that close circle, lacking all foreign policy experience, Andriy Ermak—a film copyright lawyer and film producer in his own right—currently handles contacts with the Kremlin, although there might be other channels employed as well. Former president Leonid Kuchma is (again) Ukraine’s chief delegate in the Minsk Contact Group. Apart from reinstating Kuchma in that post, Zelenskyy’s team seems determined to jettison his predecessor, Petro Poroshenko’s, Russia policy, in effect dismantling that policy’s institutional apparatus.

Poroshenko’s five-year administration had built that institutional apparatus comprised of respected professionals in the presidential administration staff, the National Security and Defense Council, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the delegation to the Minsk Contact Group, as well as the relevant parliamentary committees. They coordinated their efforts in the last three years to forestall dangers (constitutional changes under duress, Donbas “elections,” special status, Steinmeier Formula), enact a legislative shield against unilateral concessions (2018 law on Ukraine’s Donbas policy), and mobilize international support for Ukraine on those issues.

The Poroshenko administration conducted its policies on such issues with a fairly high degree of transparency and accountability, having understood the value of public support when Ukraine was faced with a tripartite Moscow-Berlin-Paris alignment in the Normandy format. Zelenskyy’s team, however, has at this early stage shown an inclination for non-transparent contacts with the Kremlin, and hopes to launch a bilateral Zelenskyy-Putin negotiation process in parallel with the Normandy process. The latter is, admittedly, risk-fraught for Ukraine, but less so than a bilateral Kyiv-Kremlin channel would be.