Putin Pushes to Call All Russian Residents ‘Russkiye’: Word for Ethnic Nation

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 26

By:

Executive Summary:

- The Russian language uses two words for “Russian.” One primarily denotes Russian ethnicity, and the other usually refers to citizens of the Russian Federation (regardless of their ethnicity).

- Due to a decline in residents declaring themselves as ethnic Russians and a desire to unify the country around himself, Vladimir Putin is calling for a shift from the political to ethnic definition, a dangerous move in a multinational country.

- This may lead ethnic Russians to become more divisive, distancing themselves from Moscow and viewing the Kremlin as their enemy.

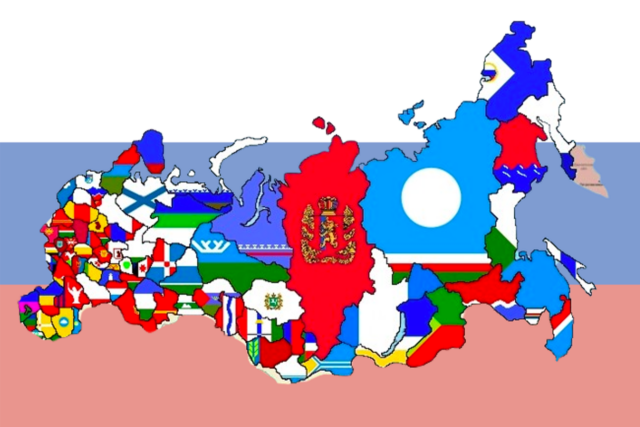

Many in the West may be inclined to dismiss a seemingly semantic dispute in Russia, which, in reality, threatens to grow into a full-scale political crisis. The dispute is related to an important nuance in the Russian language. There are two words for “Russian”: russky (русский), which generally refers to ethnicity, and rossisky (российский), which usually is limited to political life. Those who speak of Russians in ethnic terms call them russkiye. Those who speak of them as members of a civic nation are called rossiyane. In recent months, the Kremlin has increasingly been trying to promote russky at the expense of rossisky. Nearly all non-Russians and many ethnic Russians view this as an assault on their core identities. That fight has typically passed under the radar of the West because the two terms, russky and rossisky, are both translated as “Russian” in most Western languages. This discussion is now intensifying and can no longer be ignored. Russia has experienced a decline in those citizens who identify as ethnically Russian—now standing at only 71.7 percent (RBC, February 10). Additionally, many Russians and non-Russians view Moscow’s discourse as a threat to their communities and the survival of the Russian Federation (Window on Eurasia, August 30, 2018, November 9, 2022, August 6, 2023). Russian President Vladimir Putin’s desire to unite the country’s population against the West may instead alienate them from the Kremlin’s current designs.

The scale of this conflict has grown over the past few weeks as more Moscow commentators and politicians have pressed for doing away with rossisky. These commentators and politicians view the term as an unfortunate survivor of the Boris Yeltsin years. In their view, during that period, Moscow bowed to Western pressure to promote a civic identity for the new country and thus demeaned the essentially ethnic Russian nature of the country. Similar to Putin, these writers have suggested that “the term russky is broader than one specific nationality and includes all [citizens of Russia] taken together” (Govorit nemoskva, February 16).

Not surprisingly, many are not happy with this idea. One Tatar commentator spoke for many when he declared, “They are attempting to impose a new identity on us, shifting from the idea that we are all rossiyane (россияне) [members of a rossisky people] and replacing that with the identity that ‘we are all russkiye.’” The push to classify everyone as russkiye implies that they are all members of the ethnic Russian nation. The Tatarstan government canceled talks in their capital, Kazan, with Muscovite Ekaterina Mizulina, who called has supported this change (YouTube.com, February 14).

One would assume that many ethnic Russians support this call for linguistic change, which is congruent with much of Putin’s rhetoric over the past decade. Many, however, do not support this reclassification. Paradoxically, Putin’s actions may prove even more counterproductive among ethnic Russians than for the non-Russian communities. Ethnic Russians object to being lumped together with non-Russians because they see, with some justification, that such an officially imposed russky nation will resemble the concept of the multinational Soviet people and put the country on the same path that led to the disillusion of the Soviet Union (For background, see Window on Eurasia, November 16, 2016; Natsionalnyy Aktsent, November 17, 2016; Komocomolskaya pravda, November 17, 2016; MBK News, June 4, 2020; Regnum, July 28, 2023; RIA Novosti, November 25, 2023).

The tension between russky and rossisky is not a recent phenomenon. (For a survey of the dispute’s historical emergence and evolution during Tsarist and Soviet times, see Window on Eurasia, April 24, 2015; for a discussion of the controversies surrounding the relationship of the two after 1991, see Window on Eurasia, December 6, 2023.) The dispute, however, began to increase in 2016 when Putin called for a new law on the Russian nation but did not specify what the law would contain. This opened the way for a debate between advocates and opponents of the two terms (Window on Eurasia, November 1, 2016). The Kremlin leader then made things worse when, two years later, he openly advocated for the russky side (Idel.Realii, December 7, 2018). Putin did this even as he offered constitutional amendments inconsistent with that position. His approach disturbed even the most loyal of supporters on nationality affairs among Russian policymakers (Window on Eurasia, March 9, 2020).

All this might have remained of only marginal interest had it not been for the increasing confrontation between Russia and the West over Putin’s expanded invasion of Ukraine. This action simultaneously prompted the Kremlin to make ethnic “Russianness” central to its philosophy on identity in Russia, opened the way for Russian nationalists to put their spin on that drive, and sparked alarm among non-Russians over Moscow’s intentions (Window on Eurasia, November 9, 2022, August 6, 2023, November 17, 2023). Valery Tishkov, Yeltsin’s nationality minister and a leading proponent of rossisky, highlighted just how strong the winds are blowing in that direction when he declared that he was a russky too (Milliard Tatar, December 4, 2023).

The developments in Russia also wield strong influence over how the Russian language is perceived. In February 2022 , Moscow’s Federal Agency for Ethnic Affairs issued a report suggesting that civic identity, the kind reflected in talk about a rossiskaya nation, was weakening and that ethnic and regional identities were simultaneously growing (Idel.Realii, December 14, 2021; Window on Eurasia, February 3, 2022). Various Russian public figures acknowledged the shift in ethnic and regional identities occurring in their lives (Window on Eurasia, February 18). All this prompted Putin, fearful of growing division within the ethnic Russian nation and ever alert to non-Russian challenges, to tilt further away from rossisky toward russky as the identity he wants for the country.

This change in attitude may eventually exacerbate the problems Putin thinks he is solving, destabilizing his hold on power and Russia as a whole. The Kremlin leader’s shift has further angered non-Russians and Russians alike, albeit for different reasons, and increased the number of opponents his regimes face. Putin may still have time to reverse course as he has done on other issues in the past. Even if he does, however, Putin will likely create a situation in which people on both sides of the policy divide will question his leadership.