Putin Speaks but Gives Few Answers

Putin Speaks but Gives Few Answers

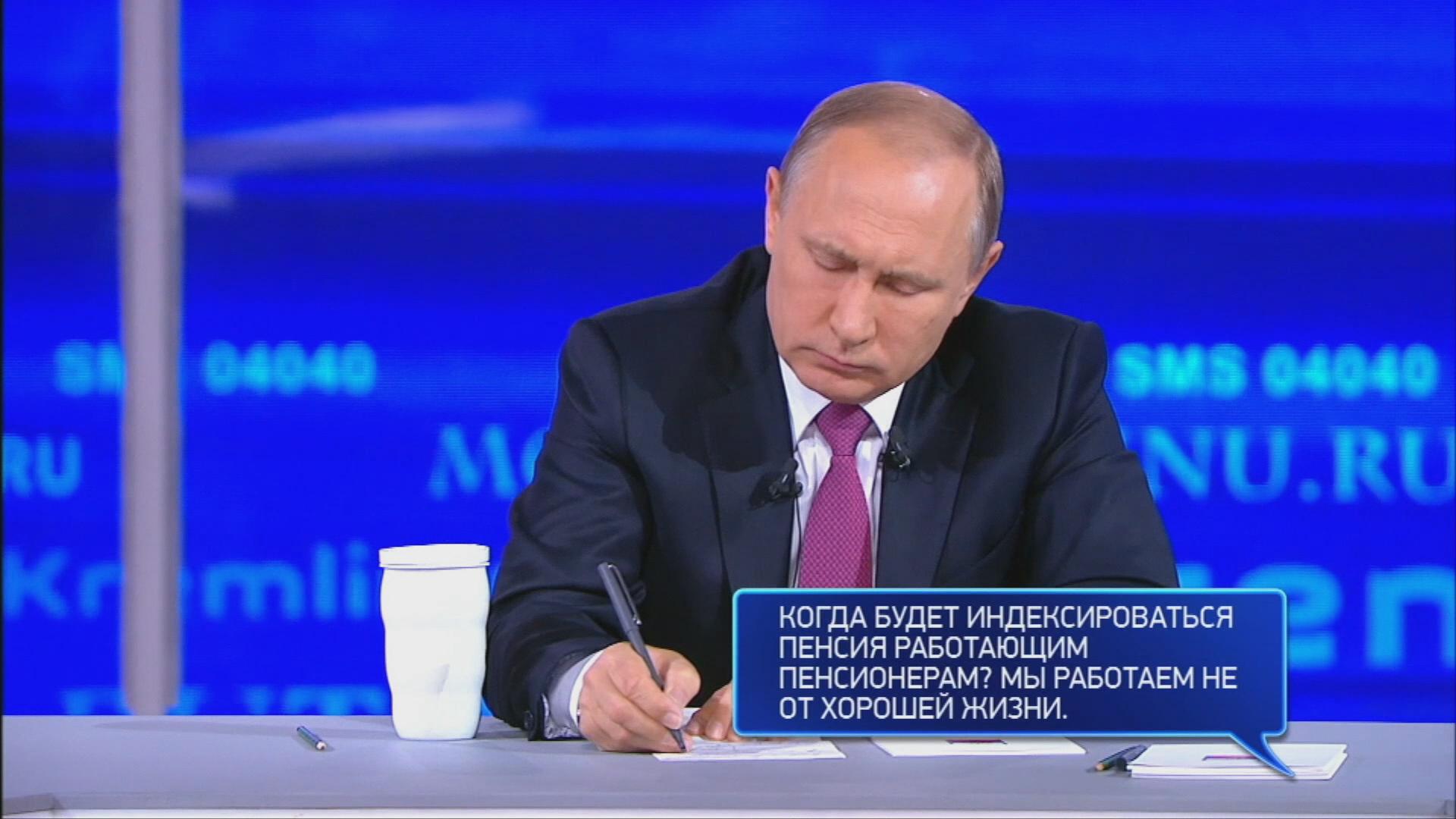

President Vladimir Putin’s annual call-in show (this year held on June 15) directed at the citizens of Russia, who can ask him any kind of question, was meant to offer a bit of fresh excitement to the boring summer political season. But Putin’s televised performance ended up looking rather dull compared to the street protests that took place earlier that week as well as the fierce debates happening online, on Russian social networks. In the course of four hours Thursday morning, Putin took 68 carefully rehearsed questions; only the surprisingly uncensored flow of mobile text (SMS) messages—like, “Is it not time for you to retire?”— provided a bit of entertainment (Newsru.com, June 15). The Russian president reassured that no decision on raising the retirement age (which is as low as 55 years for women and 60 for men) has been taken, confirmed that everything will be fine, and shared good news about the arrival of his second grandchild. He did not, however, address in any meaningful sense the big questions Russia is facing, of which there are at least five.

The question of greatest concern for the domestic audience is about the economy. Putin placed strong emphasis on the country having overcome the recession, which is technically barely correct. Moreover, macro-economic statistics continue to translate into a further decline of real incomes (Gazeta.ru, June 15). Putin handled many petty personal economic matters presented to him with habitual ease; but this distribution of presidential generosity left the impression of being little more than a drop in the bucket (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 15). The responsibility for neglecting social problems was placed squarely on governors and other local authorities who have already experienced several rounds of reshuffling and can expect more scapegoating (Kommersant, June 15). One key economic issue that received zero attention is the allocation of resources to the military-industrial complex, which is lobbying fiercely against any cuts in the yet-to-be-approved 2025 armament program (Gazeta.ru, June 15).

Foreign policy matters also received scant consideration: China, Germany, India and Turkey were not mentioned at all, even though the question of the costs and risks of Russia’s confrontation with the West is certainly of prime importance. Putin avoided any crude anti-Americanism, and he informed his audience that Russia has many friends in the United States. Furthermore, he expressed readiness to cooperate on nuclear non-proliferation, Syria and even climate change (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 16). Putin pitted the blame for tensions in Russia-US relations on “enemies” of President Donald Trump. And he characterized the former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), James Comey, as a “human rights activist”—an exceedingly negative categorization in Putin’s vocabulary of invectives (New Times, June 16). New sanctions discussed in the US Congress were, in Putin’s opinion, unfortunate but “nothing extraordinary.” Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Russian Central Bank, clarified the next day that the effect of these sanctions would be miniscule (RBC, June 16).

The question about the management of the war with Ukraine—in which the fact of armed aggression is wrapped in many layers of denials and hypocrisy—Putin addressed in an elliptic manner, with no clues about a possible way out. The Russian leader sarcastically pretended to engage in an argument with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who recently celebrated the European Union bureaucracy’s final approval of an EU-Ukraine visa-free regime and will meet with US President Trump later this week. But Putin offered no comment on when he himself might visit Washington, DC, which currently remains off-limits to the Russian head of state (Rosbalt.ru, June 16). He reaffirmed his support for the “separatists” in Donbas but also offered a vague narrative on the cultural closeness of Russian and Ukrainian peoples. It bears noting, however, that under the influence of aggressive propaganda, 59 percent of Russians now express a negative attitude toward Ukraine, and only 26 percent have a positive opinion—about the same proportions as when it comes to Russians’ views of the US (Levada.ru, June 15). There was only one brief mention of Crimea during the call-in show, when Putin confirmed the progress in building the bridge across the Kerch Strait.

The protests rallies across Russia just four days prior to Putin’s televised appearance highlighted the question of the level of the government’s readiness to suppress the rising discontent. Putin vaguely expressed a willingness to pursue dialogue with the opposition, but he condemned the purported exploitation of social problems for political purposes (Novaya Gazeta, June 16). He did not mention his main opponent, Alexei Navalny, by name (which is in fact taboo in all official media). Rather, he asserted that the problem of corruption was not particularly important for Russian society (Moscow Echo, June 16). The focal point of the Navalny-inspired protests has, indeed, shifted from corruption to the desire for change. And if the initial wave of rallies in March was surprising for the high participation of students and teenagers, the new surprise last week was the eagerness of this youthful crowd to defy official bans and restrictions on further protests (Carnegie.ru, June 13). Administrative pressure was mobilized against students, but Putin had nothing to say to this generation, which has never known any other leader and refuses to accept political ossification as the natural order of things (see EDM, June 15).

The most obvious question referred to Putin’s intentions to claim the position of supreme power for another six years. The moment looked right to launch his presidential campaign, which most argue is already pre-determined to end in triumph next March. Yet, Putin opted to postpone the announcement (RBC, June 15). Everything appears firmly under control, but doubts suddenly swirl among the elites—and, quite possibly, in Putin’s mind. The elections could perhaps be reduced to a mere technicality, but his agenda for making Russia richer and stronger is clearly exhausted. He used to be able to compensate for this by engaging emotionally with the electorate. However, this year’s call-in show demonstrated aloofness and even irritation at the endless demands for money (Snob.ru, June 15).

These five unanswered questions suggest Putin is not ready for another presidential term; and yet, he cannot avoid taking it. His freedom of choice is now much more limited than in mid-2011, when he decided to reclaim the presidency. That pre-determined blunder brought Russia economic stagnation and confrontation with the West. Today, he is trapped by the daily multiplication of abuses of power and is compelled to stay on by the pressure of propaganda panegyrics. But more decay and decline lies ahead, almost certainly resulting in resounding failure.