Regional Problems Ultimately Trump Ukraine as Defining Issue in Central Asia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 2

By:

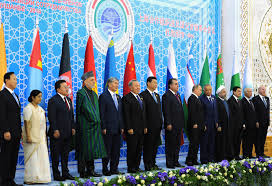

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its intervention in other parts of Ukraine, many in Central Asia and beyond concluded that the foreign and domestic policies of the five Central Asian countries would be radically and irreversibly changed by those events. Some saw Moscow’s actions in Ukraine leading the countries of that region to turn further away from Russia and seek expanded ties with the West or China in order to protect themselves against what many feared would be a Russian move against them. Other observers concluded that these countries would pursue the opposite strategy, seeking to protect their internal political arrangements by allying themselves even more closely with the Russian Federation (Interfax, April 4, 2014; The Moscow Times, March 19, 2014).

But those assumptions turned out to be wrong. In part, these notions largely failed to reflect the thinking of the elites in the Central Asian capitals. Even more importantly, however, five other influences, some new and some longstanding, trumped Ukraine as a defining issue in Central Asia. These five defining, long-term issues include the United States’ drawdown from Afghanistan, Chinese economic expansion, Russian economic power, intra-regional conflicts, and internal challenges to political control.

As a result, nine months after Moscow’s move into Crimea, the five countries of the region—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—are all following trajectories that they would most likely have chosen even if the Ukrainian crisis never happened. And this pattern is likely to continue unless there is some dramatic shift in Ukraine or in East-West relations in the coming months, or unless one or more of the five drivers of policy in Central Asia change.

What follows is a discussion that draws on year-end surveys of the countries in this region and in particular the comments of three prominent Russian experts: Stanislav Pritchin of the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies, Dmitry Arapov, a historian at Moscow State University, and Aleksandr Salikhov, a Moscow historian who specializes in Central Asia (Novaya Gazeta, December 31, 2014).

The five drivers of Central Asia’s development are:

1. American Withdrawal From Afghanistan. The most important event in Central Asia last year was the US drawdown in Afghanistan. This development signified that the United States was less interested in Central Asia than it had been. At the same time a revived Taliban now threatens Central Asia and, beyond its borders, the Russian Federation as well. Such fears have not driven Central Asians toward cooperation with one another, however—there are too many longstanding conflicts among them (see below). Instead, these looming dangers have aroused greater concerns about unilaterally defending their own national borders and expanding cooperation with Russia to prevent challenges either from the Taliban to their security, or the West to their existing political arrangements (see EDM, July 12, 2013; February 26, 2014).

2. Chinese Economic Expansion. Chinese investment in Central Asia has skyrocketed, benefitting some of the countries in economic terms but sparking fears among the elites in many of them—and in Tajikistan in particular—that Beijing will follow up its economic expansion by seeking greater political influence. This potential rise in Chinese influence inspires local worry, especially given that the US is seen as retreating from the region and Russia is left as the only alternative as a counterbalance to China.

3. Russia’s Economic Power. The Russian economy is in terrible shape from the perspective of the West, but it looks very powerful indeed from Central Asia. As a result, Moscow analysts are unanimous that Vladimir Putin can expand the membership of his Eurasian Economic Union to include all the countries of the region, except Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan—and be successful in cultivating closer economic relations with Tashkent and Ashgabat as well. The reasons are rooted in geography: Besides northward transit through Russia, The Central Asian republics lack a sufficient alternative transit corridor for their trade. And with the US exit from the region, coupled with many of these governments’ opposition to China, the Central Asian states believe they are unlikely to obtain an alternative transit route out of the region any time soon. Furthermore, most of the Central Asian countries rely on transfer payments home from guest workers in Russia—a fact that no local leader can ignore, and something the Russian government can and does exploit to gain influence.

4. Conflicts Among the Five—Territorial and Political. The five Central Asian countries continue to fight over water, over territory—there are 286 disputed parts of their shared borders in the Ferghana Valley alone, and there are tensions over larger areas like Karakalpakia between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan—and over pipelines and rail ways on which these countries depend for trade. Moreover, despite their Islamic heritage, the five have very distinctive national values that often put them at odds.

5. Internal Challenges to Political Control. Two of the five countries have aging leaders, two others face regional challenges to central control, and four of the five are worried that they will face challenges, from the Taliban or the West, to their authoritarian governments. Moscow is prepared to back these regimes uncritically in exchange for loyalty. That is something the West cannot or will not offer, even in the wake of the events in Ukraine. Thus, the policies of the five appear likely to continue along much the same paths they have in the past, the Ukrainian crisis notwithstanding.

None of this is to say that what is happening in Ukraine is not affecting the thinking of leaders in Central Asia. Instead, it is to point out the obvious that for them, as Arapov put it: “Ukraine is far away,” but Afghanistan, China and Russia are all nearby. Consequently, those factors more than Ukraine are going to define the future, at least the immediate one.