Roiling in the Deep: PRC Pushes New Deep Sea Order

Roiling in the Deep: PRC Pushes New Deep Sea Order

Executive Summary:

- New deep-sea technologies, growing influence in the International Seabed Authority, and domestic legislation are part of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) ambitions to become a strong maritime power.

- The PRC is the world’s largest net importer of critical minerals, a potential vulnerability that could be alleviated through exploiting the ocean floor. This would help reinforce its already dominant position in the critical minerals supply chain and in the manufacture of the key technologies of the energy transition.

- The International Seabed Authority is currently negotiating a mining code. The PRC has been among the most vocal advocates for opening international waters to mining and in 2023 opposed the creation of an inspection body to enforce a future code, while last year it unilaterally blocked a motion to pause mining activities out of environmental concerns.

- Deep-sea activity conducted by the PRC, including scientific research, is closely linked to the country’s military. Key institutions are subject to U.S. government sanctions and export controls, and research vessels have been caught undertaking exploration activities within the exclusive economic zones of other nations or planting the PRC flag in contested areas.

In December 2024, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) announced the commissioning of Tansuo 3 (探索三号), a state of the art deep-sea research vessel designed to facilitate surveys across most of the world’s oceans, including the Arctic (People’s Daily, December 27, 2024). A month prior, the government also unveiled the first domestically designed deep-sea drilling vessel, Mengxiang (梦想号) (State Council, November 17, 2024).

These technological developments are the result of ambitions to become a “strong sea power (海洋强国),” which entail a growing focus on the ocean floor (State Council, April, 2013). Beijing seeks to dominate the development and manufacture of the technologies of the future, including those crucial to the energy transition. These technologies often rely in part on minerals and metals that can be extracted from the seabed.

Access to the seabed is currently restricted by physical and regulatory barriers. Technological advances (and state-led investment) are making headway on the first, while Beijing’s influence within of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and willingness to ignore other states’ maritime claims have led to progress on the second. The degree to which PRC activity is conducted by the People Liberation Army (PLA) and entities affiliated with it suggests that Beijing’s interests in the ocean floor are not limited to the scientific or the commercial, but rather to its wider maritime strategy and conception of its own comprehensive national power.

Decades of Work Underpins Deep-sea Dominance

The deep sea, typically defined as water located 200 meters or more below the surface, is one of the least explored parts of the planet. However, recent developments in technology have begun to make it more accessible. As the global energy transition accelerates, the demand for critical minerals has surged. Cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements have become indispensable to achieving a low-carbon future, as they are essential for renewable energy technologies such as electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, and solar panels.

The PRC has emerged as the key player in the deep sea domain under President Xi Jinping. In 2013, shortly after assuming power, Xi unveiled plans for the PRC to become a strong sea power as part of his “China Dream (中国梦)” vision, emphasizing the need for “exploration, exploitation, and protection of the sea (开发,利用和保护海洋)” in the country’s broader developmental strategy (State Council, April, 2013). Two years later, a revision to the national security law included the protection of the country’s activities and assets in the international seabed as a critical component of national security (State Council, July, 2015). This was followed in 2016 by legislation that created a legal framework for regulating deep-sea exploration (NPC, March 2016).

The PRC has also made substantial investments in the research and development of deep-sea technology. The 13th Five-Year Plan on Scientific and Technological Innovation (“十三五”国家科技创新计划), issued in 2016, identified deep-sea technology as one of 13 strategic and forward-looking scientific priorities, and outlined six major technological projects to be achieved by 2030 (State Council, July 28, 2016).

These investments have built on decades of state-led efforts that have enabled the PRC to dominate the critical minerals supply chain. As early as 1987, Deng Xiaoping signaled an interest in the sector, stating that “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths (中东有石油,中国有稀土)” (CNR, August 16, 2007). As a result, the PRC now accounts for approximately 60 percent of global critical mineral extraction and an even larger share—85 percent—of the refining process (China Brief, October 8, 2010; March 15, 2021).

These days, the PRC relies for the most part on raw minerals from outside the country, to the extent that it is the world’s largest net importer. Over the years, it has built up its dominant position through extensive overseas investments, advanced mineral processing capabilities, and its role in manufacturing high-value components, such as batteries (The Brookings Institution, July, 2022). For instance, while the PRC holds only 2 percent of global nickel reserves and 5 percent of nickel mining, PRC companies control two-fifths of raw nickel mining and over four-fifths of the refining (ISS, April 12, 2023).

This dependency makes the PRC vulnerable to external supply shocks. For example, in 2020, Indonesia—the largest global producer of nickel—banned nickel ore exports to stimulate the development of its domestic mineral processing industry, disrupting PRC access (IEA, March 19, 2024). Although the PRC was able to substitute with imports from the Philippines, that country is now also considering an export ban or tax on nickel ore (SP Global, February 7, 2023; Business Mirror, January 29). Deep-sea mining could therefore provide an opportunity to reduce dependence on imports and increase its self-reliance.

PRC Preferences Shape the ISA

Most deep sea mineral reserves are in international waters beyond countries’ exclusive economic zones, where deep-sea mining is currently prohibited under international law. Exploration can only be carried out under a contract with the ISA, and is subject to its rules, regulations, and procedures. (The ISA is a body established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1994 that grants exploration rights for the purpose of research and prospecting.

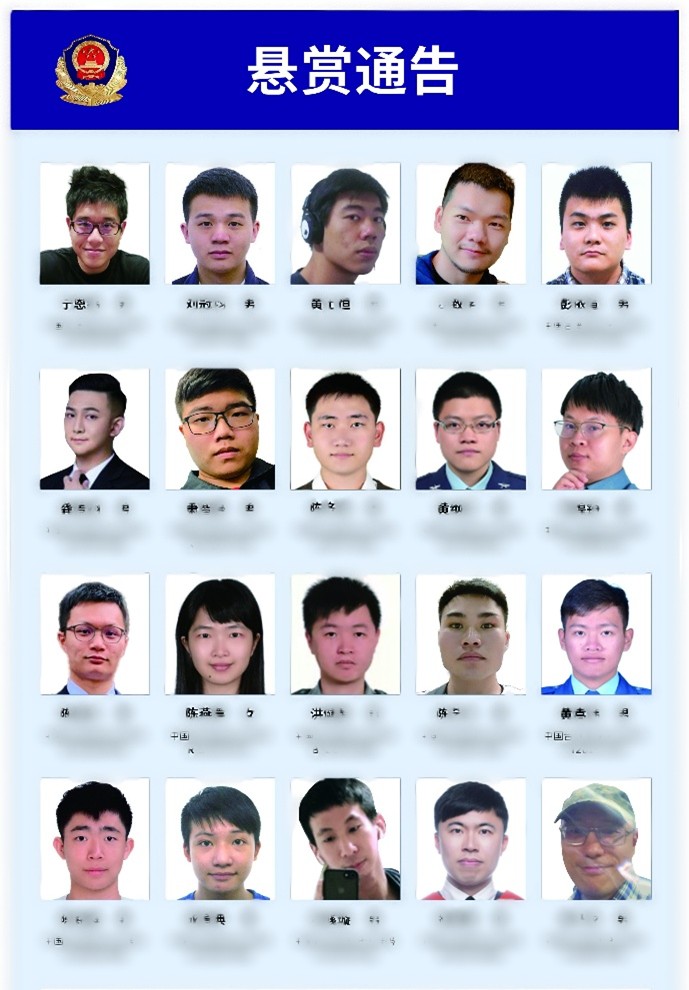

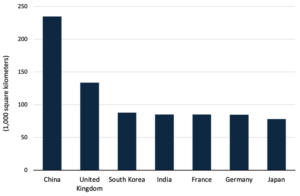

The PRC is prominent within the ISA (USNI News, November 29, 2023). It is the organization’s largest financial contributor and holds more active exploration contracts than any other nation (five out of 30). These grant the PRC access to nearly 235,000 square kilometers of mineral-rich regions in the Western Pacific Ocean, the Southwest Indian Ridge, and the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Eastern Pacific.

Viewing the ISA as an avenue to reshape the international maritime order, which it perceives as dominated by U.S. hegemony, the PRC has positioned itself as a champion of multilateralism and equality. During a UNCLOS event in 2022, a PRC delegate called for replacing the “outdated maritime order (落后时代的旧海洋规则)” with a new one based on these principles (MFA, September 2, 2022). In contrast, the United States has not ratified UNCLOS and holds no ISA contracts, though it has observer status at negotiations and the ISA has approved the extension of mining contracts issued by the U.S. government before the ISA’s creation (CRS, November 26, 2024).

Figure 1:Designated Areas for the PRC to Conduct Deep Sea Exploration

Figure 2: Area of the Sea Floor Assigned for Exploration to Countries With at Least two ISA Contracts

Further solidifying its dominance, the PRC partnered with the ISA in 2020 to establish the ISA-China Joint Training and Research Centre in Qingdao (ISA, accessed: January 21). This initiative focuses on capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology to developing countries through training workshops, enhancing PRC leadership.

At the regulatory level within the ISA, the PRC has been keen to ensure that its ambitions are not restricted. It has been among the most vocal advocates for opening international waters to mining. In 2023, it opposed the creation of an inspection body to enforce a future mining code negotiated by ISA members, and at the organization’s annual meeting unilaterally blocked a motion that advocated for a precautionary pause on deep-sea mining activities due to concerns over potential environmental consequences (ISA, February, 2023; The Guardian, July 29, 2023). [1]

Later this year, two PRC state-owned enterprises, China Minmetals (中国五矿) and Beijing Pioneer Hi-Tech Development Corporation (北京先驱高技术开发), will test their deep-sea mining equipment in ISA-designated regions (ISA, April 23, 2024; May 1, 2024). These tests are nominally for the collection of environmental data collection but the company also hopes that the results will inform future regulations (Beijing Pioneer Hi-Tech Development Corporation, May 1, 2024).

The ISA is set to finalize a mining code this year (Mongabay, July 4, 2024). This may be delayed due to unresolved disputes, but the PRC will continue to play a leading role in negotiations. As such, the opening of international waters for deep-sea mining appears increasingly likely.

Military Facet of Scientific Research

Deep-sea activity conducted by the PRC, including scientific research, is closely linked to the country’s military. A 2017 State Council Opinion called for integrating civilian and military efforts in the maritime domain, including deep-sea exploration, intentionally blurring the lines between scientific research and military objectives (State Council, November 23, 2017). As a result, the country’s main players have deep ties to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). This includes the China State Shipbuilding Corporation (中国船舶集团) and Harbin Engineering University (哈尔滨工程大学), which are the subject of sanctions and export controls, respectively, from the U.S. government (OFAC, accessed January 29; Federal Register, accessed January 29). China State Shipbuilding Corporation oversees the production of nearly all PRC naval vessels and has contributed to the development of platforms that include the deep-sea drilling vessel Mengxiang. Harbin Engineering University remains closely affiliated with the navy and supports its deep-sea operations. [2]

Advances in deep sea technology are enabling much greater understanding of this little-explored part of the planet, but they also enhance the PLA’s maritime military capabilities. For example, unmanned underwater vehicles such as the Haidou 1 (海斗一号) have demonstrated the ability to patrol the seabed for over 10 hours at depths exceeding 10,000 meters, and to conduct various mapping and communications activities. Similarly, the Kaituo 2 (开拓二号), another unmanned vehicle, can perform seabed mining at depths over 4,000 meters (SJTU, July 11, 2024). These technologies could easily be repurposed to map the ocean floor in adversaries’ jurisdictions, monitor harbor activities, or deploy anti-surface and anti-submarine weapons.

The bottom of the ocean is increasingly becoming a contested space, with a number of ships—often alleged to have ties to the PRC or Russia—apparently responsible for severing undersea cables that facilitate global information and data flows (China Brief Notes, January 16). Harbin Marine Equipment (哈尔滨船舶设备), a subsidiary of Harbin Engineering University, has developed unmanned underwater vehicles to conduct engineering surveys and maintenance (Perma, August 2, 2017). Such technologies could also be repurposed to target or compromise cable infrastructure in the event of a conflict.

The military dimension of PRC deep-sea exploration intersects with international regulatory and legal regimes in disputed waters (The Jamestown Foundation, accessed January 29). Institutions like the National Deep Sea Centre (国家深海基地) under the Ministry of Natural Resources (自然资源部) frequently conduct activities under the guise of scientific research to advance territorial claims. Research vessels have been caught conducting deep-sea exploration within the exclusive economic zones of nations such as the Philippines, Malaysia, Japan, Taiwan, Palau, and even the United States (Washington Post, October 19, 2023). Submersibles have also planted the PRC flag on the seabed in contested areas, asserting Beijing’s sovereignty in violation of international law.

Conclusion

In the PRC’s pursuit to become a strong maritime nation, it engages in efforts to reshape approaches to the deep sea. Using technologies mainly developed by entities linked to the country’s military, it seeks to expand deep-sea mining in order to acquire the necessary minerals to support its economic objectives. The deployment of vessels like Tansuo 3 and Mengxiang reflects these ambitions. Beijing has also made substantial progress influencing global regulatory bodies to better express its preferences. While some activities, including scientific research and international workshops, contribute tangible public goods, the dual-use character of its approach threatens many other countries, particularly those in the South China Sea.

The deep sea is just one of several “new frontiers (新边界)” that the PRC sees itself at the forefront of, along with the polar regions, space, and cyberspace, as an article in the overseas edition of the People’s Daily from last summer makes clear (People’s Daily, April 6, 2024). Many of the approaches Beijing uses to advance its interests at the bottom of the ocean are analogous to those used in other domains and are underpinned by the same principles. As such, implications of the PRC’s strategy to become a strong sea power are also relevant in other domains (China Brief, November 5, 2024).

The authors would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for their feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Notes

[1] The PRC later climbed down from this position and agreed to include the issue on the following year’s agenda, where it was discussed but no action was taken.

[2] Harbin Engineering University was originally called the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Military Engineering College (中国人民解放军军事工程学院).