Guardian of the Danube: Romania’s Mixed Progress in Implementing a Black Sea Strategy

Guardian of the Danube: Romania’s Mixed Progress in Implementing a Black Sea Strategy

Executive Summary

Romania’s maritime environment consists of the Danube River and the Black Sea. The river links the country to the sea providing an important trade connection with the rest of the continent as well as a natural frontier. Moreover, the Danube is crucial for Romania as it is one of the country’s most important sources of energy. Romania’s main interests in the Black Sea are ensuring peace and stability, freedom of navigation and energy security along with exploitation of the natural resources found in its exclusive economic zone.

The major conflicts of the 20th century have affected Romania’s perception concerning the importance of its maritime environment. In both world wars, the Danube and the Black Sea were strategic theaters of operations on the eastern front. Romania clashed with the great powers of the day in order to gain or secure access to the Black Sea and the Danube. Historically, however, Romania’s interest in its maritime environment has been intermittent, with periods of great activity alternating with periods of relative neglect.

After the end of the Cold War, Romania chose the Black Sea as its main strategic focus. The reasons for this choice had to do with a mix of threats, risks, and opportunities that made the region attractive. Politically, Bucharest did not want to be associated with the Balkans and their turbulent history. The Black Sea offered both strategic opportunities as well as economic ones. The region is important economically as it links Asia and Central Asia to Europe, in addition to being rich in oil and gas resources. The strategic challenges consist of prolonged conflicts in the former Soviet space and Russian aggressive behavior, which culminated in the Russo-Georgian War of 2008 and the Kremlin’s aggression against Ukraine since 2014.

Today, Romania is trying to counterbalance the Black Sea region’s strategic challenges by consolidating its relationship with the United States and by investing in its own defense. Yet these efforts have only been moderately successful to date. The US military presence in Romania is rotational and does not have the same status as the one in the Baltic States and Poland, despite that region experiencing a comparable level of threat. Moreover, Romania’s defense modernization and procurement is suffering from delays, which affect its deterrence credibility. Finally, despite significant energy production potential, most of Romania’s oil and natural gas projects in the Black Sea are being delayed, negatively impacting the country’s energy security.

Introduction: Romania and Its Strategic Maritime Environment

Romania’s maritime interests include the Danube River and the Black Sea. The Danube is Europe’s second-longest river and one of its main trading routes. One thousand and seventy-five kilometers of the lower course of the Danube runs through the country. Romania controls most of the Danube Delta and, more importantly, the mouths of the Danube, along with the main navigable Sulina canal.

The lower course of the Danube forms part of the border between Romania and Ukraine, and the latter country controls a small part of the river’s delta. In the south and southwest, the Danube divides Romania from its Balkan neighbors, Serbia and Bulgaria. The Danube–Black Sea canal, which links the river to the Port of Constanța, shortens the route for ships and freight on their way to the Black Sea. Around 236 km of the river are Romanian internal waters.[1] The Danube-Rhine canal links the two rivers together, so that, in theory, freight shipped from Constanța can reach the Netherland’s Rotterdam, the busiest port in Europe.

Besides riverine shipping, trade links with Serbia and Bulgaria are maintained by bridges and viaducts. The main bridges over the river that link Romania and Bulgaria are at Giurgiu and Calafat. Plans exist to build another bridge to boost trade and tourism between the two countries. Serbia and Romania, in turn, are linked over the Danube by a viaduct across Iron Gates I Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP) and via a bridge at Ostrovu Mare, in the vicinity of Iron Gates II HPP.

The Danube is important for Romania not only as a major trade route but also for the country’s energy security. Two major hydroelectric dams are situated on the Danube: the aforementioned Iron Gates I and II. Both are the result of the cooperation between Communist Romania and Yugoslavia in the 1970s and 1980s. Iron Gates I is the most powerful HPP in the entire Romanian conventional energy-generating system, while Iron Gates II is the third-most powerful plant of this type. Additionally, the Cernavodă nuclear power plant (NPP), whose construction began in 1982, stands on the Danube–Black Sea canal. Water from the Danube is drawn and used in the secondary circuit of the two pressurized water reactors operated by the plant

Strategically, the Danube separates Romania from the Balkans and forms a natural border with Ukraine in the southeast. In the past, the Danube partially defined Romania’s political and diplomatic identity. Notably, during the first half of the 19th century, the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia were known as the “Danubian Principalities” in diplomatic circles. The river also played a crucial role in all of the of conflicts that Romania was involved in during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Control of the Danube has been an ongoing issue for Romania since the creation of the state in the early modern period. The early Romanian state did not have the resources to properly manage the river. Moreover, up until 1878, the country was not independent but rather a dominion of the Ottoman Empire, and control of the river was coveted by both Austria and the Russian Empire.

Starting in 1856, navigation on the Danube became regulated by international and European commissions. Romania greatly resented this situation, as the existence of these bodies infringed upon its sovereignty over parts of the lower Danube. Two European commissions have regulated traffic on the Danube. The first one was created after the Crimean War in 1856 and functioned until 1948. It oversaw river navigation and administration of the maritime sector of the river, from Galați to Sulina. The commission raised taxes and had its own courts.

The Paris Treaty of 1856 additionally made provisions for an International Danube Commission to regulate traffic upstream from Galați, but this international body came into being only in 1918. The current Danube Commission was established in 1948 as the result of the Belgrade Convention of 1948, which reflected a Soviet vision regarding the river. Currently it is made up of Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Moldova, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Belgium, Greece, Georgia, Cyprus, North Macedonia, the Netherlands, Turkey, Montenegro and Czechia (the Czech Republic) have observer status. Although the Soviet Union has disappeared and Russia does not have access to the river, Moscow remains a full member of the commission. Article 30 of the Convention Regarding the Regime of Navigation on the Danube prohibits the deployment of naval vessels of non-riparian countries.[2] This provision may have a negative impact on Romania’s ability to deter and defend against potential aggression as it hinders the deployment of allied forces from the United States or other non-riparian North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states on the river.

The Black Sea represents Romania’s main link with the global market. Goods to and from Romanian ports reach other parts of the world by transiting the Turkish Straits (Bosporus and Dardanelles) into the Mediterranean Sea and then on to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The Black Sea is additionally an access point to the markets of Central Asia and onward, via land routes, to the rest of Asia. Romania hopes to take advantage of its geographical position in the Black Sea and its membership in the European Union to more deeply connect with Asian markets.

The Turkish Straits and the Montreux Convention of 1936 have given the popular impression that the Black Sea is a closed sea (mare clausum), yet it is not landlocked like the nearby Caspian. The Turkish Straits act as much as an access point as they are a barrier. Furthermore, freedom of navigation through the Straits is guaranteed and free of charge, barring some administrative costs.

The significance of Romania’s maritime spaces is reflected in its international trade. In 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, 47.2 million tons of goods transited through Romanian ports.[3] Most of this traffic passed through the Port of Constanța (83 percent) and the rest was handled by the ports of Midia and Galați.[4] Besides trade, Romanian ports double as shipyards. The main shipbuilding and repair facilities in Romania are Șantierul Naval Constanța, Midia and Mangalia (the latter two are state owned but privately managed by the Dutch company Damen). These are followed on the lower course of the Danube, close to the mouths of river, by Damen Galați, Sulina, as well as Brăila and Tulcea—the latter two owned by the Italian conglomerate Fincantieri. Further down the Danube, there are shipyards at Orșova, Turnu Severin, Giurgiu, Cernavodă and Oltenița. Romanian shipyards build, repair and modify both seagoing and riverine ships. Damen Galați is currently the only shipyard in Romania that has built and delivered military vessels for navies and coast guards around the world.

Romania’s Black Sea coastline measures 245 km (132 nautical miles), and its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) has a surface of 9,700 square km.[5] Romania’s EEZ is important from an energy security perspective as it is estimated to contain around 200 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, according to the most optimistic estimates.[6]

After Brexit, Romania became the second-largest producer of gas in the EU.[7] Bucharest’s and Ankara’s gas discoveries in the Black Sea make them the most important NATO allies in the region when it comes to energy security. In the Romanian exclusive economic zone, the following potential oil and gas deposit have been identified: Neptun Deep, Neptun Shallow, Midia, Luceafărul, Histria, Pelican, Muridava, Cobălcescu, Rapsodia and Trident. Neptun Deep is considered the most valuable discovery, with an estimated capacity between 42 and 84 bcm of gas.[8] In the Turkish EEZ, exploration efforts have identified Turkali-1, Turkali-2, Turkali-3, Danube-1 and Tuna-1 oil and gas deposits. The largest find in the Turkish zone is the Tuna-1 gas field, discovered in 2021 with an estimated volume of 320 bcm.[9]

Romania and the Black Sea During the Major Conflicts of the 20th Century

In 1905, Romania received a naval wake-up call when the mutinous Russian battleship Potemkin entered the Constanța roadstead and demanded fuel and victuals. If these demands were not fulfilled, Potemkin declared it would open fire on the port. The Romanian authorities were taken by surprise by this unwanted visitor, which was being hunted by the entire Imperial Russian Black Sea Fleet. Romania’s only naval assets in the Black Sea at that time were three French-built torpedo-boats, a British-built light cruiser and a school ship.[10] All of these warships were outdated by the beginning of the 20th century and no match for a pre-dreadnought battleship like Potemkin. Moreover, the prospect of a naval battle between the mutinous Potemkin and the Russian Black Sea Fleet outside Constanța was not something the Romanian side wished to see off its coast.

Ultimately, however, the crisis was resolved without recourse to arms. Romania gave the mutinous crew asylum or safe passage out of the country, while the latter agreed to surrender the ship to the Royal Romanian Navy.[11] When the Russian fleet arrived off Constanța to take over or sink the fugitive battleship, the Romanian navy informed its Russian colleagues of how events unfolded with the rebels aboard Potemkin and then surrendered the ship to its rightful owners.[12]

This event underscored the need for a modern and capable Romanian naval force in the Black Sea. In the early 20th century, the Black Sea region was disputed between the declining Ottoman Empire and the rapidly modernizing Russian Empire. The Potemkin mutiny illustrated that Romania, as a young state and a small power in the Black Sea region, was vulnerable not only to the geopolitical ambitions of the established regional powers but also to internal political and social developments that took place within the latter’s borders. In the aftermath of the incident, the Romanian government drew up plans for the procurement of four modern torpedo-boat destroyers but no order for maritime warships, as the policy focus shifted to the Danube.[13]

Romania simultaneously faced pressure from the Austro-Hungarian Empire regarding policing rights along the Danube. The double monarchy controlled most of the course of the river and wanted to extend this control to the lower course, which passed through Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and the mouths of the Danube. On the eve of World War I, a naval arms race on the Danube began between Romania and Austria-Hungary. Both countries invested heavily in river monitors and small riverine torpedo boats. By the time the war had broken out, Romania wielded four river monitors and eight torpedo-boats on the Danube. Furthermore, in 1915, the government finally ordered the four destroyers envisioned after the Potemkin incident as well as a submarine from an Italian shipyard. But when Italy entered the war that same year, the destroyers were taken over by Rome’s Regia Marina.[14]

Romania entered World War I in 1916 on the Entente side. Its main priority was to establish control over the traffic on the lower Danube to protect the Turtucaia bridgehead in Southern Dobrudja. The Royal Romanian Navy tried to establish its riverine supremacy on the first day of the war by launching a surprise torpedo attack on the Austro-Hungarian monitors.[15] However, the attack failed, with only one enemy supply ship sunk. The Romanian naval doctrine at that time demanded its monitors to seek combat and sink the Austro-Hungarian monitors venturing up the lower Danube.[16] As a result of this doctrine, most of the ammunition supply of the Danube Flotilla at beginning of the war was made up of semi-armor piercing shells. However, no major clash between Romanian and Austro-Hungarian monitors occurred on the river. So instead, the monitors were used to provide naval gunfire support to Romanian troops, which quickly depleted the riverine vessels’ supply of high explosive shells.[17] The Romanian monitors had to be resupplied with French-made shells via Russian ports in order to maintain readiness and defend the riverine communications.

The Russian navy, although more numerous than its Ottoman counterpart, did not seriously contest the control of the Black Sea until the first dreadnought battleships of the Imperatritsa Marya class, ordered just before the start of hostilities, entered service.[18] The arrival in Istanbul in 1914 of the German navy battlecruiser SMS Goeben and of the light cruiser SMS Breslau changed the balance of forces in favor of the Central Powers. Gifted to the Ottoman Empire by Kaiser Willhelm II, Goeben was renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Breslau became Midilli. For most of World War I, the Central Powers dominated the Black Sea.[19]

During the disastrous 1916 campaign, Romania lost most of Dobrudja, including the Port of Constanța. It maintained only a tenuous hold over the mouths of the Danube, including its main canal, Sulina. The Danube Flotilla supported the Romanian Army during the battle of Turtucaia and during the Flămânda crossing.[20] A German submarine was damaged after a brief encounter off Sulina in October 1916, with one of Romania’s torpedo boats.[21] The following year, as part of the 1917 campaign, the Romanian navy managed to sink an Austro-Hungarian river monitor, KUK Inn, near Brăila.[22] Romania’s small liners (“packet boats”) were armed and lent to the Imperial Russian Navy, which used them as auxiliary cruisers and as seaplane tenders.[23]

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Romania was forced to sue for a separate peace with the Central Powers in early 1918.[24] The Treaty of Bucharest imposed taxing conditions on Romania. According to this peace agreement, Romania lost part of Dobrudja to Bulgaria, and the rest, including Constanța, fell under the trusteeship of the Central Powers, although Bucharest maintained formal sovereignty.[25] Romania maintained control over the mouths of the Danube and received “compensation” in the form of recognition of its union with the former Russian gubernia (governorate) of Bessarabia.[26] The loss of southern Dobrudja and control over Constanța, the country’s main commercial port, represented a heavy blow for Romania’s economic development and geopolitical ambitions. Fortunately for Romania, however, the Treaty of Bucharest never came into force, and the Entente eventually won the Great War.

After the Treaty of Versailles, Romania’s coastline expanded from Cetatea Albă (today Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Ukraine) up to Ecrene (Kranevo, Bulgaria).[27] The total length of the coastline was 225 nautical miles, giving Greater Romania the third-longest coastline in the Black Sea after Turkey and the newly created Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Moreover, Greater Romania now controlled the mouths of the Danube.

The greatest security threat faced by Romania after World War I came from revisionist states that wanted to overturn the order established at Versailles. These main revisionist great powers were Germany and Soviet Russia. To complicate matters, the USSR was also Romania’s largest neighbor, with which it shared the longest land border. Furthermore, Romania had to contend with two revisionist neighbors, Hungary and Bulgaria, which claimed Romania’s Transylvania and Southern Dobrudja territories. In the Black Sea, the most important political development was the signing, in 1937, of the Montreux Convention, which established a special military regime concerning the straits of the Bosporus and Dardanelles.

The Romanian navy was strengthened with ships taken from its former enemy, Austria-Hungary—three river monitors and eight torpedo boats[28]—as well as with ships bought from its allies. The navy procured four French-built gunboats for minesweeping operations in the Black Sea and four Italian Motoscafo Armato Silurante (MAS) anti-submarine patrol boats.[29] Of the four destroyers ordered before the war from Italy, two were commissioned into service. The other two were sold to Italy’s Regia Marina in order to settle some of the war debts between the two countries.[30]

Italy would become one of Romania’s major naval suppliers during the interwar years. Two more destroyers, based on the British Thornycroft-class design, were built in Italian shipyards as well as a submarine and a submarine tender.[31] However, the Great Depression greatly affected the development of the Romanian Royal Navy. Economic woes impacted the procurement of new ships, weapons system acquisitions and training. Just before the start of World War II, Romania would purchase three motor torpedo boats from the United Kingdom and a training ship from Germany (NS Mircea, which is still in service).[32]

The local naval shipbuilding industry also contributed to the development of the Romanian navy. Between 1938 and 1939, two submarines, Rechinul and Marsuinul, and a minelayer, Amiral Murgescu, were laid down in Romanian shipyards.[33] The two submarines would be commissioned later, during World War II. A number of ships were acquired or leased from Germany during the war, but some of them, like the Dutch-built Power-class motor torpedo boats, would prove ill-suited to the needs of the Romanian navy.[34]

Following the August 1939 Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, Romania would lose Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union in June 1940. As a consequence of these territorial changes, Soviet Russia again gained access to the mouths of the Danube on the Chilia branch. Moreover, this land grab by Moscow created a vulnerable spot along Romania’s defensive perimeter on the lower Danube and the Danube Delta, allowing Soviet forces to threaten navigation along the Sulina canal. Following the retreat of Romanian forces from Bessarabia, skirmishes broke out on the Danube between Soviet and Romanian naval forces, as the border arrangements were not clear.[35] The withdrawal without a fight of the Romanian Armed Forces from the provinces of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina tempted the Soviet government to try to annex as much territory as possible.[36] The border agreement between the two countries concerning the Danube River did not follow the pre-1918 border. And this situation persisted after World War II.

When Romania entered World War II on June 22, 1941, it became the main Axis naval power in the Black Sea, playing the same role as Italy in the Mediterranean Sea. Moreover, it was the main supplier of oil and oil products to the Axis powers, as well as one of their main providers of grain and foodstuffs.[37]

The Romanian Royal Navy had to face the much larger and better equipped Soviet Black Sea Fleet. At the start of the war, the Romanian navy did not have enough modern warships and lacked intelligence concerning the strength of its enemy. With the exception of the Danube Flotilla, the navy did not train before the war in large formations.[38] In terms of equipment, it did not have enough anti-aircraft guns,[39] and its main surface combatants would fight the entire war without shipborne radar. The main missions undertaken by the Royal Romanian Navy involved protecting the Romanian coast from raids and amphibious assaults, protecting the sea lanes of the communication (SLOC), mining and minesweeping operations, as well as mounting limited attacks on Soviet controlled SLOCs.

Although comparatively small, the Romanian navy lost few warships in actual combat. Despite continuous efforts by Soviet naval and air forces to sink the main Axis surface unit in the Black Sea—the Romanian four-destroyer squadron—no ship was lost to enemy action. Both Soviet and Axis forces avoided major engagements, relying instead on mines, submarines and fast attack craft. Both sides launched amphibious operations when the situation called for them and when adequate resources were in place. The Romanian Royal Navy and the German Kriesgsmarine made use of a large number of armed merchant men, armed tugboats and armed trawlers. Both Axis and Soviet forces deployed minefields in the Black Sea on and near the main sea lanes of communication, as well as on the lower course of the Danube. Minesweeping operations were intensive and carried out by both Axis and Soviet forces at regular intervals.

In several actions and operations, the small Romanian navy, aided by its Axis allies, managed to hold out against a superior enemy in terms of ships, aircraft, firepower and manpower. Relatively few surface engagements occurred in the Black Sea, as both the Axis and the Soviets wanted to conserve their major units. Moreover, the naval war in the Black Sea region was secondary to the ground war, as the latter was the decisive theater of operations. In one of the few surface engagements of the war, on June 26, 1941, the Soviet Black Sea Fleet mounted a raid against Constanța.[40] Initially, the Soviet force achieved the element of surprise, but the raid was beaten back by the quick and coordinated reaction of Romanian destroyers aided by German and Romanian shore batteries. The Soviet navy lost the destroyer leader, Moskva, in a minefield and another destroyer, Tashkent, was damaged.

An important mission of the Romanian Royal Navy during the war was the escorting of convoys between Istanbul and Constanța, Sulina and Odessa, Constanța and Odessa, and, later, between Constanța and Crimea.[41] The most dangerous operation undertaken by the Romanian navy was the evacuation from Crimea in April–May 1944 of Romanian and German troops besieged by Soviet forces. Over two thirds of Axis troops in Crimea managed to be evacuated from Crimea in what the Romanian navy dubbed “Operation 60,000.”[42]

When Romania eventually switched sides during World War II, the Kriegsmarine ships present in its Black Sea ports were disarmed, while the rest were chased down the Danube, out of Romanian waters.[43] The Soviet navy confiscated and took over Romania’s warships and used them against the remaining Axis forces in the Black Sea region. With few exceptions, most of the ships were returned after the war.

In 1947, the Treaty of Paris redrew the map of Romania to its 1940 borders with the Soviet Union and Bulgaria.[44] Thus, Romania became the Black Sea state with the smallest shoreline in the region, compared to the pre–World War II situation, when it claimed the third-longest coast.

In 1948, Romania’s Communist government ceded Snake Island, which is actually a rock, to the Soviet Union, a move that would later complicate the maritime delimitation between Romania and Ukraine. During the Cold War, the Romanian navy, along with its Bulgarian counterpart, essentially became auxiliaries to the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, with the task of helping the latter to punch through the Turkish Straits and operate against NATO forces in the Mediterranean.

Romania’s Black Sea Policy in the 21st Century

Romania’s Black Sea policy can be divided into two main phases. The first started around 2002 and lasted until 2014. During this period, Bucharest promoted multilateral cooperation in the Black Sea, greater NATO and US presence in the region, energy security, and democratization. The highpoints of this period were the North Atlantic Alliance’s Bucharest Summit in 2007, the Georgia War of 2008, and the decision in 2011 by the United States to deploy the Aegis Ashore system in Romania and Poland as part of the Phased Adaptive Approach to deal with ballistic missile threats coming from Iran.

In 2014, the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia and the subsequent war in eastern Ukraine put an end to this phase of policy. From 2014 onwards, Bucharest’s Black Sea policy emphasized deterrence against potential aggression, as well as resilience in the face of Russia’s non-linear (hybrid) warfare in the region. Energy security took another dimension, emphasizing interconnectivity and offshore reserves. US presence in the region became crucial for stability and deterrence as Bucharest built up its military.

In the early 2000s, Romania was a candidate for accession to NATO and the European Union. Washington wanted Romania in NATO because of two major factors: the country’s military viability as well as its potential role in stabilizing the Balkans. Of all the former Warsaw Pact members, Romania came second after Poland in terms of military potential. The second wave of NATO enlargement needed to include Bucharest in order to balance out countries such as the Baltic States or Bulgaria, whose military potential was rather limited. Furthermore, during the 1990s, the country showed that it could play a stabilizing role in Southeastern Europe. Romania supported the US-led bombing campaign against Serbia in 1999 and the intervention in Kosovo. Moreover, throughout the wars in the former Yugoslavia, Bucharest deployed peacekeepers to the region.

The military and political reforms necessary to become a NATO member moved slowly in the early 2000s. However, the attacks of 9/11 changed priorities on all sides. Washington needed allies to pursue the Global War on Terror, and Romania’s relative proximity to the Middle East and Central Asia was considered an asset for US policy. Consequently, the NATO integration process was accelerated and, in 2004, Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania became seen as potential intermediate staging bases for the military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. Moreover, Romania was interested in receiving US troops on its territory and had its own agenda regarding the Black Sea.

Romania Chooses the Black Sea as a Strategic Focus

In geopolitical terms, Romania wanted to avoid becoming associated with the Balkan Peninsula, despite US plans and analyses to the contrary. For policy architects in Washington, Romania, along with Greece in the south, which was already in NATO and the EU, were seen as major stabilizing forces in the region. Besides its military potential, US officials believed that Romania could constitute a role model for the countries that made up the former Yugoslavia in terms of its treatment of minorities living within its borders. Previously, in the early 1990s, it was posited that Romania could soon follow the example of its neighbor Yugoslavia due to the existing tensions between the Romanian majority and Hungarian minority. However, by the middle of the decade, those tensions had been peacefully solved and the local Hungarian political organization seamlessly integrated into local political system. For prestige reasons, therefore, Bucharest consciously did not want to be lumped together with the Balkans. The region’s instability as well as the history of ethnic cleansing could have negatively impacted Romania’s image abroad should it decide to play a larger role in the region. Furthermore, Bucharest did not see eye to eye with Washington on the recognition of Kosovo’s independence, fearing it could set a dangerous precedent that could be used by the Kremlin in the case of Transnistria. Moreover, the main threats and opportunities for Romania’s foreign policy did not come from the Balkans.

Romania’s concerns about Russia are not based on simple Russophobia, despite the difficult history between the two countries. Certainly, Romanians often justify their fears regarding the Kremlin’s foreign policy behavior by pointing out that Russia invaded Romanian territory twelve times between the 18th and 19th centuries and that Romania was subordinated to Soviet control in the secret Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of 1939. The imposition of Communism in Romania after 1945 with the help of the Soviet Red Army is another cultural and historical point of tension in relations between both countries. Conversely, there is a tendency in Romanian public discourse to minimize the country’s alliance with the Axis powers during World War II and a limited understanding of the character of the war on the Eastern Front. That said, the main point of contention between Bucharest and Kremlin is not cultural or historical but geopolitical in nature. Russia, besides claiming preeminence in the former Soviet space, would like to have a say over the foreign policy of the countries in Central and Southeastern Europe.[45] For Romania, this is unacceptable and the main reason why, in 1997, it formed a strategic partnership with the United States and ultimately joined NATO. Moreover, in order to diminish Russian influence and apply pressure in the Black Sea, Romanian foreign policy has sought to attract a US and NATO presence in the region.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union was a geopolitical boon for Romania, but it also came with its own set of challenges. The sudden disappearance of the predominant military and ideological power in the Central and Eastern Europe in 1991, coupled with the fall of Communism in 1989, allowed Romania to choose for the first time since 1945 the course of its foreign policy. However, the disappearance of Soviet power did not mean the end of Russian attempts to maintain some sort of control over the political developments in what the Kremlin dubs its “near abroad.” Part of these attempts are now commonly called “frozen conflicts”—unresolved military struggles that developed in the former Soviet republics just as the USSR was crumbling. These conflicts notably broke out mainly in the Black Sea and the South Caucasus region: Karabakh (1988) between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Transnistria in Moldova (1990), as well Abkhazia (1989) and Ossetia (1991) in Georgia. The Kremlin drove and/or exploited these localized wars to compromise the sovereignty of the newly minted independent states and to anchor them securely into Russia’s sphere of influence.

Of all the post-Soviet frozen conflicts, the 1990–1992 war in Transnistria posed the greatest and most direct security threat for Romania. The proximity of the fighting and Russian support for the breakaway Republic of Transnistria were Bucharest’s main concerns. In this war, the industrial and Russian-speaking region of Transnistria wanted to gain independence from the newly created Moldovan state. Rebels in the breakaway republic were directly supported by the Russian 14th Army, which also assumed the role of de facto peacekeeping force after the end of hostilities in 1992. After Romania joined NATO in 2004, it sought to put the issue of the Black Sea frozen conflicts on the international agenda.

When it comes to the frozen conflict in Transnistria, Romania initially hesitated between linking the issue to the Black Sea region or to the Balkans. In the early 2000s, the latter option seemed viable due to the diplomatic focus of Western governments. At the same time, Romania hoped to pave the way for Moldova to join the EU at some point in time; while the European enlargement process in the former Yugoslav region (now dubbed the Western Balkans to erase the memories of political instability, war and ethnic cleansing) seemed to offer the best opportunity for simultaneously pushing Chisinau’s prospects along. However, Western doubts and opposition to Romania linking Moldova’s European integration path to the Western Balkans meant that this issue defaulted to Romania’s policy in the Black Sea.

The dissolution of the USSR made newly independent Ukraine Romania’s largest neighbor as well as the country with which it shared the longest border. Although Romania recognized the independence of Ukraine and its borders, the relationship nonetheless suffered from bilateral tensions over inter alia the rights of the ethnic-Romanian minority in Ukraine and maritime border delimitation in the Black Sea. The maritime delimitation issue was solved in Romania’s favor in 2009 by the International Court of Justice, in a trial that began in 2008, after all avenues of resolving the matter through bilateral negotiations had been exhausted.[46] In spite of these differences, Bucharest championed Kyiv’s Western ambitions. In 2008, at the Bucharest Summit, Romania supported giving Georgia and Ukraine membership action plans (MAP).[47] However, despite strong US support for this move, a consensus within the Alliance could not be reached.[48]

Ensuring and maintaining freedom of navigation in the Black Sea is another fundamental interest for Romania since it is a prerequisite for maintaining access to global markets for Romanian goods while permitting foreign goods and natural resources to reach Romanian ports unhindered. Moreover, freedom of navigation plays an important role in energy security—namely, allowing oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers to deliver their cargoes. Unfortunately for Romania, however, Turkey does not allow the transit of LNG tankers through the straits of Bosporus and the Dardanelles.[49]

In terms of energy security during 2002–2014, Romania’s main interests in the Black Sea had been the Nabucco and Azerbaijan–Georgia–Romania Interconnector (AGRI) natural gas projects. Both pipelines aimed to diminish Europe’s dependence on Russian gas supplies. Yet ultimately, neither came to fruition. Nabucco was put forward by Romania, Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary and Turkey, but it lacked a supply source. Various options were proposed, such as gas fields in Iraq, Egypt, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, but all proved merely theoretical. Despite being supported by the EU and the United States, Nabucco lost in 2011 to the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline project (TANAP), an Azerbaijani initiative supplied with offshore Caspian gas from Azerbaijan.[50] Nabucco lingered for a while under a less ambitious form called Nabucco-West, but the project was canceled in 2013, at which point Baku threw its support behind the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which links up to TANAP’s western end.

The AGRI pipeline project was put forward in 2010 and aims to bring Azerbaijani gas to European markets. If completed, AGRI could deliver between two billion and eight billion cubic meters of gas to European consumers.[51] However, the high cost of LNG terminals, coupled with Romania’s limited project management capacity, mean that the project has yet to leave the drawing board.[52]

Romania encountered strong opposition from Russia and Turkey regarding an increased NATO and US presence in the Black Sea. The idea of extending NATO’s Active Endeavour anti-terrorism and maritime policing mission in the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea was opposed by both Ankara and Moscow. Instead, Turkey came up with the Black Sea Harmony Initiative in 2004, which grew to encompass all of the region’s riparian states.[53] Another maritime security initiative that Romania became part of during the early 2000s was the Black Sea Naval Force, better known by its acronym BLACKSEAFOR.[54] From a Romanian perspective, this initiative has three main disadvantages: it involves Russia, it is not permanent, and the US and other Western members of the North Atlantic Alliance did not participate.

Although Romania promoted regional cooperation between 2002 and 2014, the rest of the NATO and EU member states in the region did not necessarily share its outlook. Turkey and Bulgaria had their own agendas concerning Russia, making cooperation difficult even when the Kremlin’s behavior became indisputably belligerent. Romania tried to build a working relationship with Russia to gain leverage regionally and within NATO and the EU. However, these efforts led nowhere.

A major weak point in Romania’s Black Sea policy has been its inability to modernize its naval forces. In order to have a credible maritime policy, a state needs a navy. Without a modern navy, Romania’s interest in maintaining freedom of navigation cannot be effectively upheld. In the early 2000s, the future looked promising as Romania acquired two mothballed Type 22 frigates from the UK. And by 2004, the Romanian Naval Forces became the first branch of the armed services to be fully professionalized.[55] In 2006, the authorities drew up plans for the procurement of three multi-role corvettes and four mine hunters in order to recapitalize the ageing fleet with new surface combatants.[56] However, these plans fell apart due to the financial and economic crisis of 2007–2010 and because, after Romania joined NATO, the political elite put further defense modernization investments on the back-burner.

This trend continued even after the Russo-Georgian war of 2008. The Type 22 frigates, which were supposed to undergo a refit in 2009, never did. The Romanian authorities twice tried to modernize these ships but failed both times: the first time, the tender had to be called off because of the economic downturn, while the second time, the winner of the tender, an association between the Turkish company STM and a Romanian firm, discovered that they were not licensed by the producers of the weapons systems to install them on the ships.[57]

Throughout the 2002–2014 period, Romania was moderately successful in raising the Black Sea region to the attention of the United States. US troops were deployed on a rotational basis at Mihail Kogălniceanu (MK) Air Base, near Constanța, on the Black Sea shore. MK notably supported US deployments in the Middle East and Afghanistan. The most important US military deployment to Romania was the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system, with the basing agreement signed in 2011. Construction of the Deveselu facility began in 2013, and it became operational in 2015.[58] However, Bucharest’s main aim—securing a permanent deterrent US presence on Romanian territory—was not achieved.

Deterring Russia

Russia’s forcible annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the proxy war in eastern Ukraine in February 2014 represent the greatest security threats faced by Romania since 2014. First, the covert and then overt use of force followed by territorial conquest upended what Bucharest considered the main features of the post–Cold War order: the peaceful resolution of international conflicts and the inviolability of state borders. Second, although Romania did not share a close relationship with its largest neighbor, the compromising of Ukraine’s territorial integrity was not in Bucharest’s interest and posed a regional security challenge. Third, Russian control over Crimea means that Moscow has de facto control over a part of Ukraine’s exclusive economic zone. In fact, Romania’s EEZ now borders Russia’s (claimed) EEZ in the Black Sea. In the future, there is a risk that the Kremlin may not recognize the result of the International Court of Justice’s adjudication concerning maritime delimitation in the Black Sea.

As the building of the bridge over the Kerch Strait and the virtual closing of the Sea of Azov have shown, Russia’s ambitions in the Black Sea are not limited to Crimea. In 2014, then–Romanian president Traian Băsescu expressed anxiety that Russia ultimately aimed to reach the mouths of the Danube.[59] These fears were justified by Russia’s actions in 2014–2015 in southwestern Ukraine, in the Crimea and Odesa regions,[60] as well as Moscow’s use of the concept of “Novorossiya” (a term dating back to tsarist imperial times) to denote these territories.[61] Had Russian-backed rebels been successful in taking over Odesa in 2014 and the Black Sea Fleet occupied Serpent’s Island, the Kremlin would have been in a position to interdict all maritime traffic near the mouths of the Danube.

Following the annexation of Crimea, Russia proceeded to beef up its military presence in the newly acquired territory. Today, Crimea is being used as a power projection springboard to the Black Sea region and the Eastern Mediterranean. Indeed, Russia’s interventions in Syria and Libya would arguably have been much more difficult without Crimea.

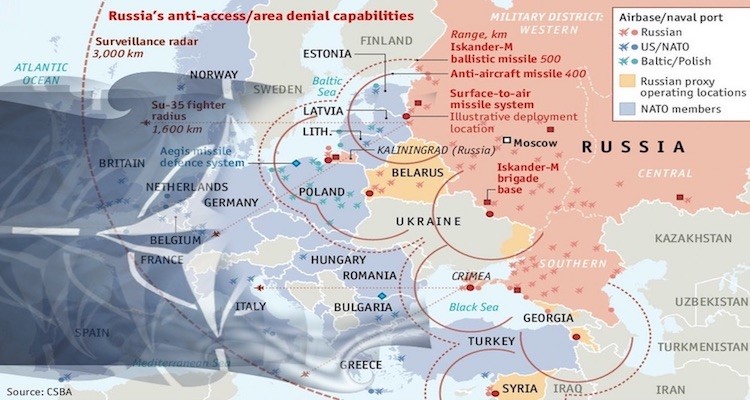

The Black Sea Fleet was modernized with diesel-electric submarines and new surface combatants. And Russia deployed long-range air-defense systems like the newly introduced S-400 system, alongside long-range land-based anti-ship missiles, creating an anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) zone.[62] The purpose of this bubble is to protect the newly acquired territories and keep NATO out of the region. The transatlantic alliance’s maritime access to the Black Sea was already constricted by the Montreux Convention, which limits the number, type and time spent by military vessels belonging to non-riparian states; but it has now been further hampered operationally by the deployment of Russian A2/AD systems. Furthermore, Russia reinforces its dominance of the northern basin of the Black Sea by regularly designating large swaths of water as no-go-zone exercise ranges for its ships and aircraft.[63]

The Kremlin has been deploying the Kalibr family of missiles on its Black Sea Fleet surface combatants and on submarines, in both land-attack cruise missile and anti-ship variants.[64] An innovative solution to compensate for Russia’s inability to build surface combatants larger than guided-missile frigates has been the deployment of Kalibr missiles in vertical launchers on corvettes and fast-attack craft. In Western navies, long-range tactical land-attack missiles are deployed on guided-missiles frigates, destroyers and nuclear-attack submarines. Russia’s innovative solution allows it to exercise control in the Black Sea region with limited means and minimum effort.[65] Furthermore, since 2018, the shipyards in occupied Crimea have begun building surface combatants for the Black Sea Fleet, the air-bases on the peninsula are being modernized, and Russia has deployed high-performance multi-role and strike aircraft.[66] Russia’s actions in the past seven years have tipped the military balance in the region in its favor and transformed Crimea into a bastion from which the Kremlin can project power both within and outside the region.[67]

The Russian takeover of Ukraine’s EEZ off Crimea and the cordoning off of the Azov Sea raise serious questions concerning maritime security for Romania. Bucharest’s plans regarding offshore exploitation may be thwarted by the Kremlin’s use of hybrid warfare tactics and legal obstruction. In 2020 the State Duma passed a law that allows the Russian government to ignore decisions taken by international bodies if they run contrary to its interests.[68] The presence of naval special forces (Naval Spetsnaz) in Crimea, trained in assaulting offshore oil rigs and in taking control over civilian vessels, means that Russia has the means to interfere with the offshore activities of the rest of the Black Sea riparian states.[69]

Romania’s response to Russian revisionism and revanchism in the Black Sea region has been twofold. On one hand, Bucharest began a process of internal balancing by investing in the modernization of its armed forces. On the other hand, it initiated a process of external balancing by promoting a Black Sea agenda within NATO and the EU.

In 2015, Romania pledged it would begin allocating 2 percent of its GDP to defense beginning in 2017.[70] The purpose of this decision was to jump-start the process of modernizing the Romanian Armed Forces, which had been neglected in the past. Defense expenditures were neglected after Romania joined NATO and became an afterthought when the 2008 economic crisis erupted. Consequently, most of Romania’s military equipment was obsolete and the Armed Forces faced serious readiness challenges. The purpose of increased military spending was not just to increase Romanian military capabilities but to signal Bucharest’s determination to its allies regarding a greater regional role.

Defense expenditure is presently concentrated in big-ticket items such as long-range air-defense systems, multi-role fighters or long-range mobile fires necessary for territorial defense. In 2017, the parliament approved an ambitious $10 billion procurement program for Romania’s Armed Forces; however, most of these acquisitions suffer from delays due to acquisition and administrative issues.[71] The Romanian navy is the most affected by these procurement delays. For example, the flagship naval modernization program, the procurement of four multi-role corvettes, has been stalled for the past four years due to litigation. Conversely, the programs that are being delivered on time are those that have been awarded to US defense contractors through the Pentagon’s Foreign Military Sales system: Patriot-long range air-defense missiles ($3.9 billion), HIMARS rocket systems ($1.5 billion), F-16 AM/BMs from Portugal (with US support) and Naval Strike Missiles ($286 million). Despite being oriented toward territorial defense, Romania’s modernization plans have yet to address areas where the country is vulnerable or faces equipment deficits, such as modern self-propelled artillery systems and heavy armored fighting vehicles (tanks and infantry fighting vehicles).

After 2020, Romania’s defense sector began investing in its defense-industrial base and barracks infrastructure. This is an important part of the country’s defense policy as it seeks to attract the US and other NATO allies to base their troops on its territory. The most ambitious base modernization project involves extensions and upgrades for the MK air base, valued at €2 billion ($2.25 billion) over ten years.[72] After the base is finished, it will be able to accommodate both US and Romanian troops. The extension of the MK base represents, politically and symbolically, a Romanian response to Russia’s fortification of Crimea.

On the diplomatic front, Bucharest has renewed its efforts to maintain allied focus on the Black Sea region. Romanian authorities were disappointed by NATO’s decision to deploy rotational, rather than permanent, forces along the Alliance’s Eastern Flank in 2014. And perhaps even more critically, Bucharest lamented the divergent statuses of Allied deterrence postures between the northern and southern portions of the Eastern Flank. On the northern (Baltic) sector of the flank, the status of the US and allied presence is that of Enhanced Forward Presence. This is in part justified by the vicinity to Russia’s Western Military District—its best equipped military district and the one with the most troops.[73] The Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, the Baltic Fleet and the Suwałki corridor add to the strategic importance of the northern end of the Eastern Flank, raising the necessity of maintaining a credible deterrence posture there, particularly given that the four northeastern NATO member states share a direct border with Russia.

On the southern (Black Sea) sector of the Eastern Flank, in contrast, the US and allied presence has the status of “Forward Tailored Presence.” The main deployments are in Romania and Bulgaria and consist mostly of US troops, with some Polish troops deployed as part of the Multinational Brigade South-East. In order to give more weight to Bucharest’s military status on the Eastern Flank, Romania has hosted the HQ Multinational Headquarters South-East at Sibiu and in the country’s capital since 2020.[74] Although the Russian Southern Military District does not have as many troops or firepower as the Western Military District,[75] the Black Sea and Crimea are the starting points of Moscow’s power projection into the Eastern Mediterranean.

Romanian efforts to encourage a single approach within NATO toward the Eastern Flank have been negatively impacted by the differing approaches to Russian security policy among the Black Sea allied member states themselves. Bulgaria did not support Romania’s idea of a NATO flotilla in the Black Sea, while Turkey alternates between cooperation and competition with Russia.[76] Ankara has shown it can confront Moscow in the Eastern Mediterranean, Ukraine and the Caucasus without generating a strong counter-response. Although Turkey’s confrontations with Russia serve only its interests, they show that a strong posture toward the Kremlin has benefits. Building and consolidating a single strategic vision for the Black Sea riparian member states remain an ongoing challenge for Romanian diplomacy.

After 2014, Romania redoubled its efforts to promote Black Sea issues within NATO and the EU by helping establish several major multilateral groupings. In 2015, Romania and Poland created the Bucharest 9 format, which brings together all the member states on the Eastern Flank to better coordinate their actions within the Alliance. Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Slovakia, Poland and Romania meet periodically as part of this forum to work out their differences and influence decision-making decisively within the Alliance. The inclusion of Bulgaria, Hungary and, to a lesser extent (particularly recently), Czechia, which want cooperative relations with Russia despite its aggressive moves, ensures that differences are smoothed over or at least that these states have an avenue where they communicate their points of view without necessarily compromising wider Alliance consensus.

The other format promoted by Romania since 2014 is the Three Seas Initiatives (3SI), which is also the result of inter alia cooperation between Bucharest and Warsaw. 3SI reunites states that border the Baltic, the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea: the Baltic States, Poland, Austria, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. The aim of this format is the economic development of both Central and Southeastern Europe via regional cooperation and interconnectivity. In this way, member states hope that the region will gain more substance and clout in the EU.

Relations between Romania and Ukraine have improved after 2014, but there are still tensions regarding Ukrainian language law[77] and administrative reforms.[78] In a sign of the changing security environment, both countries have begun conducting naval exercises regularly on the Danube.[79] Moreover, in August 2020, the two governments signed a technical agreement concerning defense cooperation.[80] The agreement entered into force in 2021.

Romania’s interest in finding a solution to the frozen conflicts around the Black Sea has not abated. The persistence of these conflicts 30 years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union represents a major security challenge and threat to European security. The possibility of Russia trying to “freeze” the current fighting in Ukraine would create the largest frozen conflict in the region and increase regional instability and insecurity. Romanian diplomacy is attempting to put the frozen conflicts on the EU foreign policy agenda.[81] Heretofore, the frozen conflicts in the Black Sea region have been mostly ignored by the EU and generally considered part of the “cost” of doing business with Russia. But as Bucharest contends, the extension of such conflicts in the former Soviet space near the borders of the EU should not be neglected in Brussels as it has direct impact on the security of all member states.

On the energy front, Romanian authorities have been dragging their feet regarding offshore oil and gas extraction. In 2018, the parliament finally passed a law regulating offshore oil and gas extraction, but the foreign companies involved in offshore projects in Romania have roundly criticized it for being too cumbersome and imposing rather high royalties.[82] Despite promises that the law will be amended, the Romanian parliament has yet to take any action. Exxon, the company that had obtained rights to exploit the most important offshore gas and oil field in the Black Sea, Neptune Deep, withdrew from the project, citing excessive regulation.[83] The window of opportunity regarding offshore gas extraction is rapidly closing as the EU is trying to move away from fossil fuels and wants to transform the European economy to reflect this objective.

A positive development in terms of energy security has been cooperation with the United States in nuclear energy. Bucharest and Washington will work together to build Units 3 and 4 of the Cernavodă nuclear plant and modernize Unit 1.[84] The project, worth $8 billion, should be implemented in 2021–2031.[85] The US convinced the Romanian government to give up on a similar agreement reached with China.[86] Furthermore, both countries have decided to conduct research in civil nuclear energy and develop small modular reactors. The implementation and success of these projects, however, depend on improving the Romanian government’s administrative capacity.

Conclusion

Romania has been moderately successful in its bid to put Black Sea issues on NATO’s and the EU’s agendas. It has also managed to more tightly involve the United States in the region. Romania plays host to the US Aegis Ashore missile-defense system and to American troops; however, these troops are deployed on a rotational basis. Bucharest thinks that the foreign soldiers currently stationed on its territory are not enough to deter potential aggression. Moreover, it looks to change the status of this deployment to match the US and Allied deployments in Poland and the Baltic States. Yet Bucharest faces an uphill battle on both counts: Washington’s strategic priority is the Indo-Pacific region, and US rotational deployments to the Black Sea may well be the best that can be achieved in the current security environment. A more attainable option for Romania might be to call on its allies in Europe to send their troops to the southern sector of the Eastern Flank.

The level of ambition of Romania’s Black Sea policy is decoupled from the means available to the state. The most striking feature of this situation is reflected in the lack of meaningful investment in Romania’s Naval Forces to enforce and defend the country’s offshore claims and interests. Romania’s inability to modernize its navy has diminished its capability to pursue its interests in the Black Sea as well as undermined its credibility as a net security provider in the region. A shortage of modern ships and other naval means reduces the opportunities for cooperation with the US and other NATO countries on whose naval presence Bucharest counts for deterrence in the Black Sea. Romanian decision-makers have yet to truly internalize that a maritime policy requires a navy.

The strategic and economic linkage between the Danube and the Black Sea has also not been realized. The river and the sea represent a single geopolitical space and should be viewed as a whole. Any serious maritime policy needs to recognize this simple fact and factor it into a final analysis. Looking at this issue through a historical lens, it seems that Romania, mostly for want of resources, failed to fully exploit the strategic and developmental potential of the Black Sea. This is one of the main lessons of the 20th century for Romania’s policymakers.

Finally, energy security remains a sore point for Romania. Despite ambitious plans and efforts, it has few demonstrable achievements. The most important Romanian project concerning energy security, the development of offshore gas and oil reserves, has yet to begin, and the window of opportunity is rapidly closing as the EU and the global economy prepare to move away from fossil fuels. In nearly every major facet of security in the Black Sea region, therefore, time for Bucharest to address these mounting challenges is running out.

Notes

[1] Mihai Panait, “Perspective de dezvoltare instituțională durabilă a Forțelor Navale Române în perioada 2016–2035,” in Buletinul Forțelor Navale, Nr. 24, 2016, 86.

[2] Danube Commission, “Convention regarding the regime of navigation on the Danube, 1948,” https://www.danubecommission.org/dc/en/danube-commission/convention-regarding-the-regime-of-navigation-on-the-danube/.

[3] Răzvan Diaconu, „Volumul de mărfuri încărcate/descărcate în porturile maritime româneşti a scăzut cu peste 11% în 2020,” Curs de Guvernare, March 14, 2021, https://cursdeguvernare.ro/volumul-de-marfuriincarcate-descarcate-in-porturile-maritime-romanesti-a-scazut-cu-peste-11-in-2020.html.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Nicu Durnea, “Rolul Forțelor Navale Române în apărarea intereselor țării în bazinul Mării Negre la începutul mileniului III,” Buletinul Forțelor Navale, Nr. 19, 2013, 33.

[6] Melania Agiu, “Zăcămintele din Marea Neagră, puse în pericol. Ce se întâmplă dacă investiţiile în proiectul Neptun Deep nu demarează în 2022,” Adevărul, April 8, 2021, adev.ro/qr8zxe.

[7] Romania Insider, “Romania remains second-biggest gas producer in EU,” August 31, 2020, https://www.romania-insider.com/ro-second-biggest-gas-producer-eu-aug-2020.

[8] Offshore Technology, “Neptun Deep Gas Field Project, Black Sea,” Offshore Technology, accessed November 30, 2021, https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/neptun-deep-gas-field-project-black-sea/.

[9] Dilara Hamit, Gozde Bayar and Jeyhun Aliyev, “Turkey discovers major Black Sea natural gas reserves,” August 21, 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkey-discovers-major-black-sea-natural-gas-reserves/1949231.

[10] Raymond Stănescu and Cristian Crăciunoiu, Marina Română în Primul Război Mondial, (Bucharest: Modelism, 2000), 28–29.

[11] Andreea Croitoru, “Rolul ofițerilor de marina români în soluționarea crizei Potemkin – 110 ani de la evenimente,” Buletinul Forțelor Navale, No. 22, 2015, 77–79.

[12] Ibid., 80–81.

[13] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 24.

[14] Marian Moșneagu, Fregata-Amiral Mărășești (Bucharest: Editura Militară, 2014) 19.

[15] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 71–74.

[16] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu. 28.

[17] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 29.

[18] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 52–53.

[19] Lawrence Sondhaus, The Great War at Sea. A Naval History of the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 106–107.

[20] Michael E. Barret, Prelude to Blitzkrieg. The 1916 Austro-German Campaign in Romania (Bloomington: Indiana University Press) 127–133.

[21] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 138.

[22] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 215.

[23] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 261–266.

[24] Glenn E. Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront in World War I (Lawrence: Kansas University Press, 2011), 281–282.

[25] Keith Hitchens, România 1866–1947 (Bucharest: Humanitas, 1994) 275–277.

[26] Torrey, 283-284.

[27] Nicolae Koslinski and Raymond Stănescu, Marina Română în Al II-lea Război Mondial Vol I (1941–1942) (Bucharest: Făt Frumos, 1996), 19.

[28] Stănescu and Crăciunoiu, 272–273.

[29] Ibidem.

[30] Marian Moșneagu, 20–21.

[31] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol. I, 22–23.

[32] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol I, 23.

[33] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol I, 20–22.

[34] Koslinski and Stănescu, Vol II, 85–91.

[35] Jipa Rotaru and Ioan Damaschin, Glorie și Dramă. Marina regală română 1940-1945 (București: Ion Cristoiu, 2000) 26–32.

[36] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol I, 50.

[37] Rotaru and Damaschin, 181–185.

[38] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol. I, 25–27.

[39] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol. I, 158.

[40] Rotaru and Damschin, 47-50.

[41] Koslinski and Stănescu Vol. I, 186–283.

[42] Rotaru and Damaschin, 132–155.

[43] Rotaru and Damaschin, 197–223.

[44] Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român (Bucharest: Univers Enciclopedic, 1997), 463–466.

[45] Janusz Bugajski, Pacea Rece. Noul Imperialism al Rusiei” (Bucharest: Casa Radio, 2005), 183.

[46] Ministerul Afacerilor Externe, “Prezentarea cazului Delimitarea Maritimă în Marea Neagră (România c. Ucraina),” https://www.mae.ro/node/24347.

[47] Adrian Vierița, “The Bucharest Summit: Romania’s Perceptions of NATO’s Future,” Wilson Center, March 26, 2008, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/the-bucharest-summit-romanias-perceptions-natos-future.

[48] NATO, “Bucharest Summit Declaration,” April 3, 2008, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm.

[49] Murat Temizer, “Can Ukraine receive LNG via the Bosphorus?” Anadolu Agency, March 31, 2015, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/natural-gas/can-ukraine-receive-lng-via-the-bosphorus/11002.

[50] “Gas pipeline deal sidelines original Nabucco project,” EurActiv, June 28, 2012, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/gas-pipeline-deal-sidelines-original-nabucco-project/.

[51] Eugenia Gușilov, “BLACK SEA LNG: Dreams vs Reality,” ROEC, April 17, 2019, https://www.roec.biz/project/black-sea-lng-dreams-vs-reality/.

[52] Ibid.

[53] “Turkish -Russian declaration on Operation Black Sea Harmony,” OSCE, January 25, 2007, https://www.osce.org/fsc/23842.

[54] W. Alejandro Sanchez, “Did BLACKSEAFOR Ever Have a Chance?” E-International Relations, November 8, 2012, https://www.e-ir.info/2012/11/18/did-blackseafor-ever-have-a-chance/.

[55] “Istoric,” Forțele Navale Române, accessed November 30, 2021, https://www.navy.ro/despre/istoric/istoric_10.php.

[56] Indira Crăsnea, “O cronologie a referirilor privind programul de achiziţie şi dotare cu corvete a Forţelor Navale Române,” Defence &Security Monitor, January 13, 2019, https://monitorulapararii.ro/o-cronologie-a-referirilor-privind-programul-de-achizitie-si-dotare-cu-corvete-a-fortelor-navale-romane-1-9081.

[57] Mariana Iancu, “Cheltuiala fabuloasa fara finalizare. De ce n-a reusit statul roman in 11 ani sa modernizeze doua nave de lupta pentru care a platit 116 milioane de lire sterline,” Adevărul, May 8, 2017, https://adevarul.ro/locale/constanta/cheltuiala-fabuloasa-finalizare-n-a-reusit-statul-roman-11-ani-modernizeze-doua-nave-lupta-achitat-116-milioane-lire-sterline-1_59106f485ab6550cb8e7b098/index.html.

[58] “Participarea României la Sistemul de apărare antirachetă,” Ministerul Afacerilor Externe, accessed November 30, 2021, https://www.mae.ro/node/1517.

[59] “Traian Băsescu: Nu s-a schimbat dorința Rusiei de a ajunge la gurile Dunării, ci putința,” Digi24, December 12, 2014, https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/actualitate/politica/traian-basescu-nu-s-a-schimbat-dorinta-rusiei-de-a-ajunge-la-gurile-dunarii-ci-putinta-337818.

[60] Roman Goncharenko, “The Odessa file: What happened on May 2, 2014?” Deutsche Welle, May 5, 2015, https://www.dw.com/en/the-odessa-file-what-happened-on-may-2-2014/a-18425200.

[61] Sergei Loiko, “The Unraveling Of Moscow’s ‘Novorossia’ Dream,” Deutsche Welle, June 1, 2016, https://www.rferl.org/a/unraveling-moscow-novorossia-dream/27772641.html.

[62] George Vișan and Octavian Manea in “Black Sea in Access Denial Agea. Special Report,” edt. E. Gușilov, January 2016, https://www.roec.biz/project/black-sea-in-access-denial-age/, 5-21.

[63] Jeff Seldin, “US, NATO Slam Russian Plan to Block Parts of Black Sea,” Voice of America, April 16, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/europe_us-nato-slam-russian-plan-block-parts-black-sea/6204673.html.

[64] “The Military Balance 2020,” IISS, (Routledge: London, 2020), v.

[65] Benjamin Brimelow, “Russia’s Navy is making a big bet on new, smaller warships loaded with missiles,” Business Insider, April 1, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/russian-navy-betting-big-on-new-smaller-warships-with-missiles-2021-4.

[66] “The Military Balance 2020,” IISS, 170.

[67] Igor Delanoe, “Tracking Black Sea Security Issues. Crimea, a Strategic Bastion on Russia’s Flank”, December 18, 2014, Russian International Affairs Council, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/blogs/igor_delanoe-en/1588/

[68] “Russia approves bill allowing national law to trump international treaties,” Reuters, October 28, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-politics-law-idUSKBN27D1AF.

[69] H.I. Sutton, “Naval Spetsnaz in Hybrid Warfare. Illustrated analysis of near-term Russian maritime Special Forces underwater vehicles and capabilities,” Covert Shores, December 2, 2014, https://www.hisutton.com/Naval%20Spetsnaz%20in%20Hybrid%20Warfare.html.

[70] “Acord politic naţional privind creșterea finanţării pentru Apărare (13 ianuarie 2015),” Presidency.ro, January 13, 2015, https://www.presidency.ro/ro/presedinte/documente-programatice/acord-politic-national-privind-cresterea-finantarii-pentru-aparare-13-ianuarie-2015.

[71] Victor Cozmei, “Ministrul Apararii cere Parlamentului sa aprobe un program de 9,3 miliarde de euro pentru inzestrarea Armatei. Printre tintele programului: Reluarea achizitiei corvetelor, doar 94 de transportoare blindate si sisteme de rachete pentru aparare anti-aeriana,” Hotnews, April 11, 2021, https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-esential-21709213-ministrul-apararii-cere-parlamentului-aprobe-program-9-3-miliarde-euro-pentru-inzestrarea-armatei-printre-tintele-programului-reluarea-achizitiei-corvetelor-doar-94-transportoare-blindate-sisteme-rach.htm.

[72] Mircea Olteanu, “MApN organizează o licitație în valoare de 2,1 miliarde lei pentru lucrări de infrastructură la Mihail Kogălniceanu,” Umbrela Strategică, March 8, 2021, https://umbrela-strategica.ro/mapn-organizeaza-o-licitatie-in-valoare-de-21-miliarde-lei-pentru-lucrari-de-infrastructura-la-mihail-kogalniceanu/.

[73] “Military Balance,” IISS, (London: Routledge, 2021), 167.

[74] Headquarters Multinational Corps South-East, https://mncse.ro/app/webroot/en/pages/view/73.

[75] “Military Balance,” IISS, (London: Routledge, 2021), 167.

[76] “Bulgaria respinge, din nou, ideea unei flotile în Marea Neagră,” Digi24, August 14, 2016, https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/externe/ue/bulgaria-respinge-din-nou-ideea-unei-flotile-in-marea-neagra-549714:

[77] Dan Alexe, “Ucraina limitează învățământul în limbile minoritare, inclusiv româna,” Radio Europa Liberă Moldova, January 3, 2021, https://moldova.europalibera.org/a/ucraina-limiteaz%C4%83-%C3%AEnv%C4%83%C8%9B%C4%83m%C3%A2ntul-%C3%AEn-limbile-minoritare-inclusiv-rom%C3%A2na/31031467.html.

[78] “Convorbirea Președintelui României, Klaus Iohannis, cu Președintele Ucrainei, Volodîmîr Zelenski,” Presidency.ro, May 12, 2020, https://www.presidency.ro/ro/media/comunicate-de-presa/convorbirea-presedintelui-romaniei-klaus-iohannis-cu-presedintele-ucrainei-volodamar-zelenski.

[79] “Riverine 2018, exercițiu româno-ucrainean pe Dunăre,” Statul Major al Forțelor Navale, September 6, 2018, https://www.navy.ro/eveniment.php?id=318.

[80] “Ucraina și România, au semnat un acord de cooperare tehnico-militar,” Embassy of Ukraine in Bucharest, September 5, 2020, https://romania.mfa.gov.ua/ro/news/ukrayina-ta-rumuniya-pidpisali-mizhuryadovu-ugodu-pro-vijskovo-tehnichne-spivrobitnictvo.

[81] Bogdan Aurescu, “Tackling frozen conflicts in the EU’s own neighbourhood,” EUObserver, January 19, 2021, https://euobserver.com/opinion/150638.

[82] Kevin Crowley and Bryan Gruley, “The humbling of Exxon,” Bloomberg, April 30, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2020-exxonmobil-coronavirus-oil-demand/.

[83] “Popescu: Romgaz poate prelua participaţia Exxon la Neptun Deep, are o capacitate financiară mai mare decât Petrom,” Energynomics, November 20, 2020, https://www.energynomics.ro/ro/popescu-romgaz-poate-prelua-participatia-exxon-la-neptun-deep-are-o-capacitate-financiara-mai-mare-decat-petrom/.

[84] Roxana Petrescu, “Acordul de 8 mld. $ dintre România şi SUA pentru energia nucleară a trecut de Parlament: Proiectele nucleare vin cu dublu avantaj: costuri competitive şi zero emisii de CO2. Vor fi create 9.000 de locuri de muncă,” Ziarul Financiar, June 24, 2021, https://www.zf.ro/companii/energie/acordul-8-mld-s-dintre-romania-sua-energia-nucleara-trecut-parlament-20155114.

[85] Ibid.

[86] “Chinezii, înlocuiți cu americanii pentru energia nucleară din România,” Digi24, October 9, 2020, https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/economie/energie/chinezii-inlocuiti-cu-americanii-pentru-energia-nucleara-din-romania-138206.