Rosneft Pipelines to and Through Mongolia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 81

By:

Events in Ukraine create both uncertainties and opportunities in Ulaanbaatar. A changing balance of power in Europe and closer ties between two regional powers, Russia and China, certainly create new uncertainty for Mongolia. With their country’s “regionless” fate of living between two giants, politicians in Ulaanbaatar have been cautious in their remarks regarding the events in Europe’s East, though they clearly prioritize political stability. Even the US Ambassador to Mongolia’s call over social media for Mongolians to support Ukraine did not inspire much excitement within this landlocked Asian country (https://mongolia.usembassy.gov/oped_041014.html). But on the economic side, Mongolians are expecting some spillover effects from increased economic activities between Russia and China because of the rifts between Russia and its European partners.

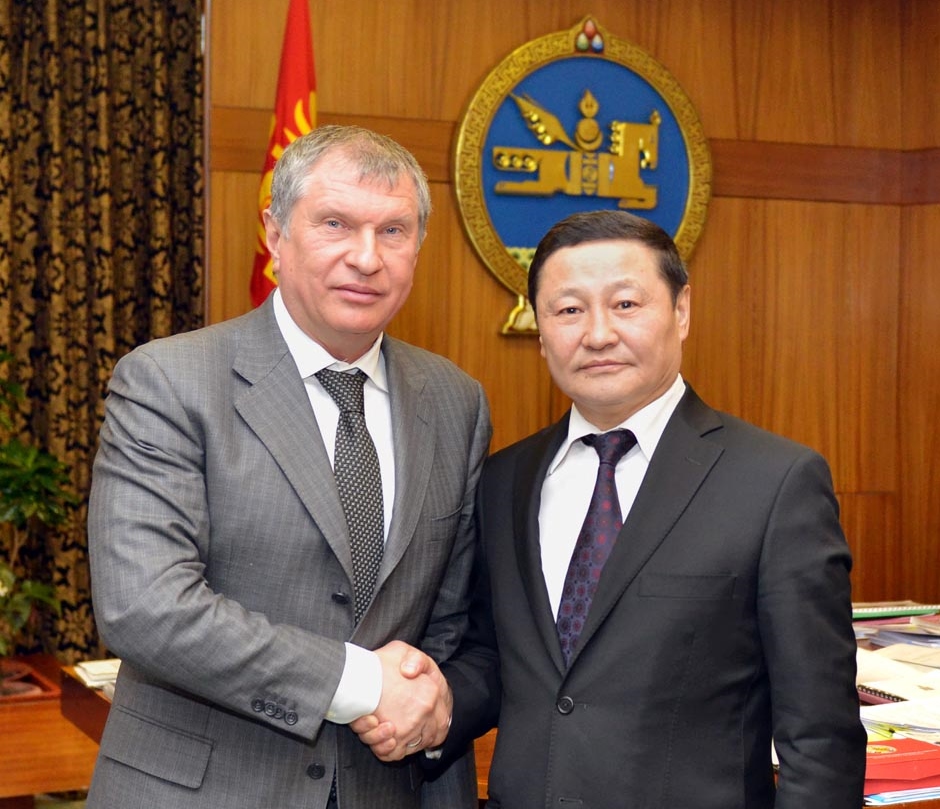

Moscow and Ulaanbaatar have for years been actively engaging in dialogue to increase the bilateral levels of trade, investment and cultural exchanges. But the actual implementation of any major plans has been slow. Mongolia’s import of fuel from Russia remains the most important, though exceedingly complex issue, at any level of inter-governmental meetings between the two neighboring states. Yet, presumably, with the recent visit to Mongolia by Igor Sechin, the president of Russian oil giant Rosneft, energy talks might finally speed up.

During his three-hour stay in Ulaanbaatar on March 17, 2014, Sechin met with President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, Prime Minister Norovyn Altankhuyag and Mining Minister Davaajav Gankhuyag. The Rosneft president informed his hosts of Russia’s willingness to supply oil to Mongolia via pipeline on a long-term basis, and he even discussed the possibility of transiting crude oil from Russia to China through Mongolian territory. In 2013, Mongolia imported 700,000 tons of crude oil from Russia, equal to 54 percent of its total domestic consumption (https://www.mongolia.mid.ru/en/press_102.html; news.mn, March 19).

There are several clear reasons for why the Russian government has become so forthcoming to Mongolia. For one, the landlocked country is still regarded as small but growing and reliable market for Russian fuel exports because of Mongolia’s increased mining and agricultural activities in addition to a rising number of individual consumers there (meaning, mainly, vehicle operators).

Second, all previous governments in Mongolia have been attempting to reduce the country’s dependency on Russian gasoline and petroleum product imports; they have struck deals with China, Kazakhstan and others as potential sources for Mongolia’s domestic energy needs (Xinhua, May 17, 2013; news.mn, Jan 6, 2009). In addition, Mongolia’s search for new sources of energy—such as shale oil exploration—are ongoing (https://en.mongolianminingjournal.com/content/21938.shtml). Russia’s sudden expanded interest in Mongolia is, therefore, likely a reflection of its unwillingness to lose any more market share for Russian gasoline exports.

Third, after much debate, Mongolia has finally begun building the country’s first oil refinery in Darkhan City, which is scheduled for completion by 2015. The new refinery will process 2 million tons of oil per year using crude oil from the Tamsag deposit in eastern Mongolia. This new refinery is also planning to import crude oil from Angarsk in Russia (https://www.infomongolia.com/ct/ci/5482; english.news.mn, March 19). In order to maintain its dominance in the Mongolian fuel market, earlier in 2011, the Russian side had offered to set up 100 gas stations in Mongolia (see EDM, November 11, 2013). But the proposal triggered sudden protectionist debates among Mongolian politicians, fuel distributors and the public. This time, the Russian side offered to deliver oil products and crude oil via pipelines because of the inefficiency of the Russian-Mongolian inter-state rail links.

Besides a pipeline to Mongolia, the Russian side also indicated it would reconsider the planned oil and gas pipeline transit route from Russia to China (infomongolia.com, March 17). At the height of joint efforts by Russian and Chinese governments to reduce the United States’ interests in Central Asia in 2005, Russia and China decided to build a pipeline that would by-pass Mongolia, even though the Mongolian route is considered shorter, safer and, therefore, more economically efficient than pipeline routes through Central Asia or via Siberia/Manchuria. Over the years, this has been one of Ulaanbaatar’s continued requests to Beijing and Moscow (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-07-02/mongolia-pushes-russia-china-to-re-route-planned-gas-pipeline.html). The finalized pipeline deal was to be made this coming May during the Chinese-Russian summit.

Although Mongolia is in many ways geopolitically constrained by its powerful neighbors, any shifts, either amicable or hostile, between China and Russia, have presented both challenges and opportunities for Mongolia. During an amicable period in the 1950s for relations between Moscow and Beijing, the first ever trans-Mongolian railroad was built, which still serves as a rail link between Russia and China for the transportation of goods and people. On the other hand, in the hostile period of the 1960s for Moscow and Beijing, Mongolia was able to benefit from Soviet developmental aid—as a legacy of that assistance, the Erdenet copper mine continues to account for a substantial portion of Mongolia’s GDP (IMF Country Report No. 07/30—Mongolia: 2006, January 2007). Today, Russia urgently looks eastward for markets for its energy exports due to tensions with the West over Ukraine. And because of this, Mongolia will likely be able to position itself to host a Russia-to-China oil transit pipeline.