Russian Federal Districts as Instrument of Moscow’s Internal Colonization

Russian Federal Districts as Instrument of Moscow’s Internal Colonization

At the end of June 2018, President Vladimir Putin named six plenipotentiaries to run Russia’s so-called “federal districts” (RBC, June 26). Four were holdovers, the remainder—new appointees. But all of them, notably, had close links to the Kremlin bureaucracy or the “power ministries” (siloviki). In May, Putin separately re-nominated the presidential plenipotentiary for the Far Eastern federal district; while the individual at the head of the Volga district was named in 2011.

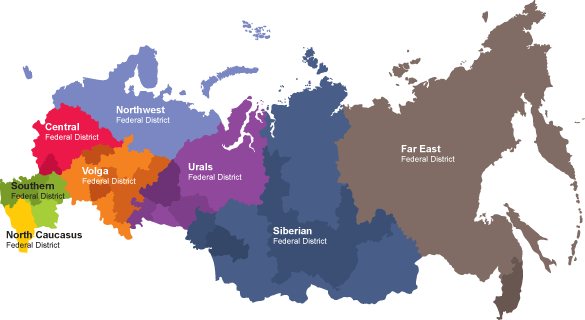

Russia has eight federal districts: Central, Northwestern, Southern, North Caucasian, Volga, Ural, Siberian and Far Eastern. Their establishment was the first managerial decision taken by newly elected President Putin in May 2000, although the districts as an institution are not envisaged by the Russian Constitution. Their geographical extent closely mimicked that of Russia’s seven military districts (the North Caucasian federal district was carved out from the Southern district in 2010). The federal districts and presidential plenipotentiary positions were created to exert Kremlin control over regional governors and republican heads, who, in 2000, were still freely elected by the population. However, even after Putin assumed appointment powers for governors in 2004, the federal districts were retained. And they have continued to function after the nominal return of gubernatorial elections in 2012 (see EDM, November 20, 2017).

Each of the eight federal district plenipotentiaries manages up to 100 employees, including “chief federal inspectors” who work directly in the regions. All these officials receive the high salaries of Kremlin employees because they are officially classified as part of the presidential staff. As a rule, they have no prior connections with the territories that they are instructed to control. In practice, this has frequently meant low interest in pursuing regional development initiatives (see below). Rather, their main task is to monitor and ensure that the Kremlin’s orders are followed down at the regional level. In this way, they represent the ideal of Putin’s “vertical of power”—one that in no way depends on voters (see EDM, November 17, 20, 2017).

Upon their introduction, the federal districts were met with general approval. They seemed like a reasonable way to manage Russia’s huge territory: a “golden mean” between Kremlin centralism and the administrative division of Russia into 85, often small, federal subjects. Well-known urbanist Vyacheslav Glazychev expressed the hope that the federal districts would become an effective basis for the development of the country (Glazychev, 2004).

However, from the outset, evidence started to build that such hopes would be misplaced. In 2000, journalists from regions within the Northwestern federal district proposed the creation of inter-regional mass media outlets. These regions (which include St. Petersburg, the Republic of Karelia, Murmansk, and Veliky Novgorod) are interrelated economically and culturally, but are alienated from one another in a media sense; even today they do not have joint television channels or newspapers. Yet, the district’s leaders declined to back the project, saying there was no need for it.

The plenipotentiaries’ inability or lack of interest in developing stronger ties among the regions under their district continues to this day. Yury Trutnev, whom the Russian media has singled out as one of Putin’s most influential plenipotentiaries, has led the Far Eastern federal district since 2013; he was reappointed to his post earlier this year. Trutnev recently complained that 70 percent of towns in the Russian Far East are not connected by air routes. Fedot Tumusov, the State Duma deputy from Yakutia, consequently asked, “It is good that the plenipotentiary speaks about the problem publicly. But would it not be better if he said what the state intends to do about it?” (Rosbalt, July 3). Indeed, Trutnev has not proposed any concrete solutions, and the Russian Far Eastern regions remain economically depressed (see Jamestown.org, September 13, 2016).

In his 2011 book, Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience, Professor Alexander Etkind notes that, unlike other past empires whose colonies were far away, tsarist Moscow imposed colonial-style tools of control even on nearby Russian lands. This model, which arguably persists today, explicitly precludes regional self-government. And “viceroys” from the metropolis can be used interchangeably. For example, Nikolai Tsukanov, who in 2016–2017 was Putin’s plenipotentiary in the Northwest, was appointed plenipotentiary in the Ural federal district earlier this year (RBC, June 15, 2018).

Regional communities have no control over the Kremlin’s appointees, who regularly avoid responsibility not only for corruption, but also for more serious crimes. For example, in 2017, the Central district’s chief federal inspector for Yaroslavl region was accused of manslaughter in a hunting accident. But the Kostroma regional court released him of all criminal charges and slapped him with an insignificant fine (less than $1,500) rather than a prison sentence. He remains in his post (Pasmi.ru, January 23).

Nevertheless, regime loyalists continue to hope for reforms of the federal districts. Political scientist Maxim Fomin says Russia needs economic decentralization and has suggested transforming these districts into “project federal territories” (Vedomosti, July 3). This, however, would represent precisely the sort of political-economic restructuring that central authorities fear: If federal districts can launch their own development projects, it would violate the “vertical of power” principle that is the main reason for the districts’ existence.

The processes of colonization and decolonization are historically ambivalent, however. Some observers have noted that the federal districts of Russia roughly correspond to the boundaries of states and principalities that existed before the formation of the Russian Empire—Muscovy, Novgorod republic, Siberia, etc. (Afterempire.info, June 28). The former Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky, who foretold the collapse of the Soviet Union back in the early 1980s, evaluated the creation of federal districts ironically, in 2003: “We were wondering into what parts Russia will be divided [i.e., break apart]. But Putin created seven districts, and now we know” (Newsru.com, December 1, 2003).

Historically, the weakening of central power in Russia repeatedly led to periods of imperial disintegration. Most dramatically, this happened twice in the 20th century—in 1917 and 1991. Putin is not immortal, and it is debatable whether the political system he has created will outlast him (The Conversation, August 2, 2017). Nonetheless, it is at least possible that a new post-imperial political arrangement could emerge in Russia after his exit from the Kremlin. And if it does, it could very well focus on the level of the federal districts, since many Russian regions are too small and dependent on their neighbors to become sovereign political subjects.