Russia’s Energy Strategy 2035: A Breakthrough or Another Impasse?

Russia’s Energy Strategy 2035: A Breakthrough or Another Impasse?

On April 2, Russia adopted the “Energy Strategy 2035” (ES-2035) planning document (Minenergo.gov.ru, April 2). As noted by Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, the country’s fuel and energy complex (FEC) is a driver of domestic economic growth; therefore, “we need to start planning now for how to continue our energy policy once global markets have recovered” following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic (Minenergo.gov.ru, April 2). The energy document suggests that the Russian FEC will become the “central pillar of Russia’s economy in the upcoming decade.” And the domestic economy itself will undergo two major changes: a shift toward “resource-innovative development” as well as a transition of the FEC from a “donor” to the “locomotive of the Russian economy.”

To achieve these broad goals, the ES-2035 puts forth five key objectives (Government.ru, April 2). First is boosting domestic consumption to a qualitatively new level, to be achieved through the introduction/implementation of an integrated complex of measures aimed at modernizing the FEC. Specifically, these measures will consist of inter alia new financial transparency requirements among leading players/corporations operating on the Russian market, the gradual liquidation of some sectoral subsidies, and greater transparency on tariffs.

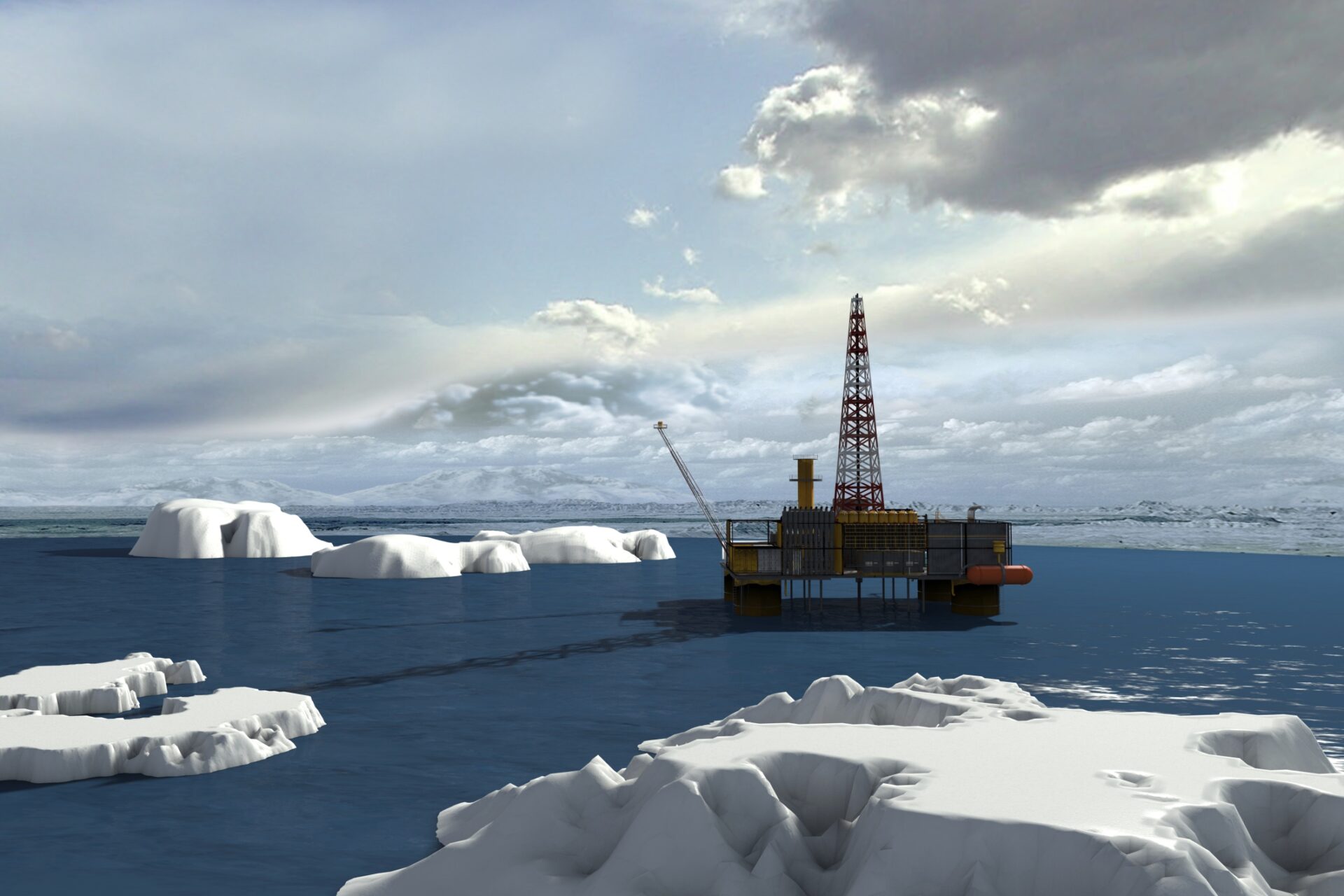

Second is a greater diversification of exports, drawing particularly on investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG), whose production is to increase by 3.4 times by 2024. Within the scope of this objective, two LNG clusters are to be completed, on the Yamal and Gyda peninsulas (Sever-press.ru, April 3). Furthermore, the ES-2035 states that Russia should develop in-country production of hydrogen and helium to become one of the global leaders in the hydrogen economy.

Third is the modernization and development of Russia’s FEC infrastructure. This will involve increasing the gasification of the Russian regions, developing energy infrastructure in Eastern Siberia and the Far East and completely integrating them into the wider Russian energy infrastructure system, as well as commercially developing the Arctic region and the Northern Sea Route, in particular.

Fourth is achieving technological independence and increasing national competitiveness. This is to be accomplished via domestically produced technologies, which falls within the import substitution strategy adopted by Russia after 2014.

Fifth is digital transformation, premised on several essential pillars: the digitalization of the FEC; increasing the role of artificial intelligence (AI), which is to attain 100 percent penetration (by 2035) in some areas of the FEC, such as electricity meters; the introduction of AI-based systems of control of electricity grids; and the realization of the National Technological Initiative (launched in 2014) aimed at the development of a domestic cybernetics market by 2035.

This optimistic plan faces some substantial obstacles, however, which cast doubt on the feasibility and main postulates identified in the ES-2035. Namely, the implementation (and feasibility) of the strategy document could be challenged by the following factors.

First is the retrograde nature of the ES-2035, as illustrated by a stress-test conducted by the Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation (Minenergo) in line with the energy strategy’s outlined requirements. Notably, the Minenergo’s stress-test identified five main threats and risks faced by the Russian FEC:

- The rapid growth of new energy-sector technologies;

- The globalization of the world energy market;

- Growing competition, primarily posed by LNG and shale oil;

- Increasing non-competitive means of economic competition (a.k.a. sanctions);

- Promotion of green (renewable) energy.

Analysis of these above-identified risks vividly underscores that Russia perceives any type of external competition to its leading global energy position—including emerging new players as well as structural trends related to the transformation of the global energy market—as existential threats that must be mitigated/eliminated rather than as incentives or potential opportunities for adaptation/innovation.

The second hindrance to fulfilling the ES-2035 involves Russia’s internal competition/transparency issues. For instance, while the document argues for increasing both, officials from the Minenergo are pushing for greater state subsidies and earmarking large funds for specific projects developed by Russia’s largest energy companies (Neftegaz.ru, April 29). As notoriously highlighted by Gazprom’s Nord Stream Two and TurkStream gas pipelines, some of those Russian energy project are clearly of dubious commercial value and grossly overstate their resource potential (Lenta.ru, May 28).

Third, as noted by some leading Russian academics, the ES-2035—though filled with such concepts as “innovation,” “effectiveness,” “social-orientation,” “development of human capital” and “eco security”—in effect, provides no real solutions or definitive proposals on how to modernize the FEC. Nor does the document explain how the errors of the past could be corrected. Specifically, the energy strategy fails to provide any viable clarification on how FEC regulations might be changed/adjusted to fit new market realities defined by (relatively) inexpensive hydrocarbons. Furthermore, the document does not pay due attention to the nexus between energy extraction and ecology—in many ways a continuation of Soviet-era practice (Natalia Zhavoronkova, Yuri Shpakovsky. Energeticheskaya Strategiya-2035: Pravovii Problemy Innovatsionnogo Razvitiya i Ekologicheskoii Bezopasnosti, 2020).

A fourth (somewhat unexpected) issue might also challenge the implementation of certain aspects of the new energy strategy. Namely, the gasification of the Kamchatka region—planned by the Russian gas company Novatek and including the creation of an LNG terminal—is reportedly being thwarted by the Russian navy, the Military-Maritime Fleet (Voyenno-Мorskoi Flot—VMF). The overall annual capacity of the terminal, to be completed by 2022, is to reach 21.7 million tons. Undoubtedly, a non-fulfillment of this project will result in “huge economic losses” (RBC, March 31). Incidentally, this is happening despite an explicit order coming from Yury Trutnev, the presidential envoy to the Far Eastern Federal District, who has repeatedly stressed the instrumental importance of this project for regional economic development (Kamchatinfo.com, April 29). While the VMF has so far abstained from any comments on the subject, presumably its position is primarily stipulated by the fact that the defense ministry has its own plans for Bechenivka Bay (where the LNG terminal is to be established), which, potentially might include the restoration of a Soviet-era military base (Neftegaz.ru, April 1).

In the final analysis, as noted by Mikhail Krutikhin (the co-founder and partner of RusEnergy, a Moscow-based independent analytical agency), the ES-2035 “is a terrible document… Russia persists in selling its oil, gas and coal to the rest of the world, and everything that obstructs this goal is considered to be a peril and a challenge” (Rosbalt, May 28).