Russia’s Eroding Influence in the Middle East

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 144

By:

Executive Summary:

- The first anniversary of the war in Gaza has revealed the near-total disappearance of Russia’s influence in the Middle East, as it has not been able to partner with those averse to US positions.

- Moscow hopes to exploit the shift in international attention toward the Middle East and away from the war in Ukraine to expose the United States’ inability to manage the escalation of multiple violent crises.

- Russia invests substantial effort in presenting itself to the Global South as a champion against a Western-dominated world order, but its support for violent disruptors in the Middle East reveals the deficiencies of this posturing.

Escalation over the last year of the decades-long conflict in the Middle East has exposed the near-total disappearance of Russian influence from the region. Historically, Moscow excelled at exploiting outbreaks of regional violence and was poorly equipped for promoting peace processes. In the current fast-moving crisis, however, Russia has not been able to partner with those who oppose US positions. The only feeble signal from the Kremlin in recent days was a statement of “serious concern” by Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, who described the possibility of Israeli strikes on nuclear facilities in Iran as unacceptable (RIA Novosti, October 3). Former US President Donald Trump, however, who has praised Russian President Vladimir Putin and his regime, suggested worrying about the consequences of a strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities after the destruction (Rossiiskaya Gazeta, October 5). Russia is desperately trying to maintain its position in the world, which is dwindling due to its war in Ukraine. Its meager efforts to influence the situation in the Middle East highlight the reputational damage it has sustained among global powers.

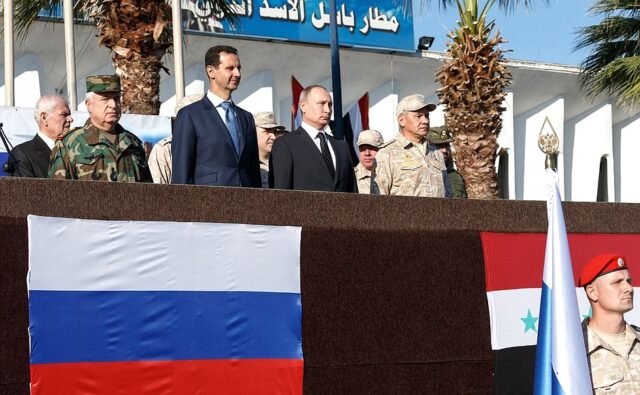

Previously, Syria was Russia’s main bastion in the Middle East, but Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s abbreviated visit to the Kremlin in July of 2023 illustrated Damascus’ weakening dependency on Moscow and Tehran as the pivotal source of support (see EDM, November 27, 2023, July 29; Kommersant, July 25). Russia’s military command has no knowledge about, nor control over, the supply of Iranian arms to Assad’s regime, and Russian media is only capable of circulating basic reports, such as one covering Israeli strikes on a smuggling tunnel under the Syrian-Lebanese border (Interfax, October 4). This is in contrast to Israel’s strike on Russia’s Khmeimim airbase on October 3, which was hardly reported on. Only a few “patriotic” bloggers dared to clarify that the target was an Iranian munitions storage facility, not the Russian base itself. The facility, constructed close to the perimeter of the airbase, was destroyed, while the expectation that Russian surface-to-air systems would intercept the incoming missiles was not met (News.ru, October 3).

Nothing is left of the long-cultivated “special relations” between Russia and Israel, and Putin no longer communicates with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (see EDM, June 20, 2016; Svoboda.org, October 4). Currently, Russian and Israeli cooperation is limited to the evacuation of Russian citizens in Lebanon. Mainstream media in Russia has been critical of Israeli air strikes and land operations against Hezbollah in Lebanon (Izvestiya, October 4).

Russian political scientist Stanislav Tarasov maintains that Hezbollah will prove to be a formidable fighting force despite Israel’s recent decapitation of the organization’s current leadership. The attacks on Hezbollah are a major blow to the Kremlin’s interests, as the organization has aided the Russian military intervention in Syria (Izvestiya, October 3). Reflecting on this setback, Aleksandr Bortnikov, the long-serving Director of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), warned that the explosion of pagers in Lebanon, which incapacitated hundreds of Hezbollah fighters, pointed to a potential threat to the Russian leadership through “destroying the critical information infrastructure, but also to organize attempts on government representatives using portable electronics at the right time” (MK.ru, October 4).

This stretch of imagination reveals the current anxiety in the Kremlin about a looming war between Israel and Iran, Russia’s main ally in the region (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, October 3). Putin has sought to boost Russian support for Iran, recently approving a treaty on a comprehensive strategic partnership, which he signed along with Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian in Moscow (see EDM; Interfax, September 18). Presently, however, the plan for formalizing close relations with such a failure as the Iranian regime is distinctly less attractive, as Iran has also fallen out of ranking in the world order and the plans for the North-South International Transport Corridor (INSTC) as a means to avoid Western sanctions appear rather premature (see EDM, June 7, 2023, March 6; Riddle, October 1).

Iran has earned tangible rewards from Russia by exporting not only drones but also hundreds of short-range ballistic missiles to the country, despite official denials (Forbes.ru, September 7; see EDM, September 18). Moscow is compelled to reciprocate by supplying Iran with advanced military technologies, but one self-made complication is the over-vigilant FSB’s investigations and arrests of many scientists, disrupting research on hypersonic missile projects (The Moscow Times, October 2).

Moscow previously used every surge of hostilities in the Middle East to its advantage, especially in oil. The first week of October saw the benchmark price of Brent crude oil only rise 5 percent, despite the high risk of Israel’s strike on Iranian oil terminals (The Moscow Times, October 4). This is explained in large part by Saudi Arabia, the main lever steering this market which has become irritated by repeated breaches of production quotas agreed to by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+) members (RBC, October 2). Russia resorts to dubious deals in exporting oil through its “shadow fleet” of tankers, which increases market instability and undermines confidence in the regulatory powers (Carnegie Politika, October 2). Moscow is willing to use such methods as it needs every extra petro-dollar to reduce the deficit incurred by its war-focused budget, including running the risk of angering Riyadh (Meduza, October 1).

With the shift of international focus toward the Middle East, Russia hopes to exploit relatively diminished concerns about the war in Ukraine and the exposure of the United States’ inability to manage the escalation of violent crises to its own political advantage (RIAC, October 2). The West is attempting to push back against these efforts. Last week, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) new Secretary General Mark Rutte sought to make it clear to Russia that Ukraine remained the top priority for the alliance by visiting Kyiv (Vedomosti; NV.ua, October 3). This week’s high-level meeting in the Ramstein format will be chaired by US President Joe Biden, suggesting that impactful decisions will be taken, including granting Ukraine permission for the use of long-range Western weapon systems (Izvestiya, October 3).

The West’s reaffirmation of support for Ukraine highlights the issue of escalation. Putin seeks to sharpen this issue further by upping the ante in his nuclear brinkmanship (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, September 30; see EDM, October 2). The Middle East offers a new perspective on this issue as both Israel and Iran seek to deter the other as well as weaken their opposition’s confidence in their respective capacities to deter escalation. Beijing and New Delhi’s warnings to Moscow on the grave consequences of the first use of nuclear weapons, however, reduce Russia’s ability to escalate tensions (Kommersant, October 3).

Russia invests substantial effort in presenting itself to many state actors in the Global South as a champion against the Western-dominated world order. Moscow’s readiness to embrace such violent disruptors of stability in the Middle East as Hezbollah in Syria and Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza and the West Bank, and the Houthis in Yemen reveals the deficiencies of this posturing. Each Israeli strike on the infrastructure of these radical groups accelerates the erosion of Russia’s positions in the region and undercuts its capacity for waging its unwinnable war in Ukraine.