Russia’s Moves to Gain Dominance in the Black Sea

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 32

By:

Russia’s primary objectives in the Black Sea region are to maximize its strategic and maritime influence there, isolate Ukraine and Georgia, weaken the cohesion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization on Black Sea security issues, and limit access to the area through the Turkish Straits for the navies of the United States and other extra-regional NATO members. A December 2015 incident in which Russia hijacked two Ukrainian offshore natural gas drilling rigs provides interesting insight into this wider Russian strategy.

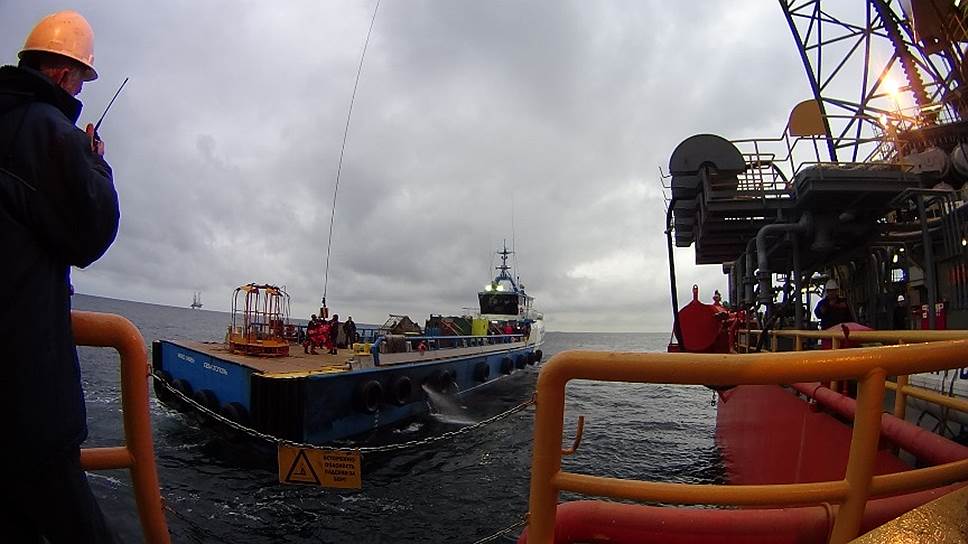

On December 14, the jack-up drilling rigs “Petro Hodovanets” and “Ukraina”—both assets of the Ukrainian firm Chornomornaftogaz, which was wholly seized by the Russian state when it illegally annexed Crimea in March 2014—were hauled away from their location on the Odesa gas field, 100–120 kilometers south of Odesa city (thus well within Ukraine’s exclusive economic zone), by Russian tug boats. Russia replaced these modern drilling rigs with the Ukrainian drilling platform “Tavrida,” which had also been captured in Crimea (112.ua, January 5, 2016). During their removal, the gas rigs were escorted by vessels of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and Federal Security Service (FSB) border guards. The operation was observed by a Ukrainian border patrol boat in the Black Sea (TASS, December 14, 2015).

The State Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) noted that the country had lost access to the “Petro Hodovanets” and “Ukraina” drilling rigs since the annexation of Crimea. Ukrainian authorities had, therefore, proposed imposing asset freezes and other sanctions against Chernomornaftegas (112.ua, December 24, 2015). Ukraine’s foreign ministry spokesperson Maryana Betysa criticized Russia’s removal of the rigs, calling it a violation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and a wide-scale robbery of assets and natural resources by an aggressor state that occupies part of Ukraine’s sovereign territory (112.ua, December 16, 2015).

Russia denied these charges, presenting the Chornomornaftogaz rigs’ removal as an internal corporate matter. The illegally nationalized company’s CEO, Igor Shabanov, claimed that the rigs were removed because of an elevated “terrorist threat.” Shabanov also mentioned that the territory where the rigs were operating had “undetermined international legal status” (Kommersant, December 15, 2015). Each of those charges was thoroughly dismissed by researchers at independent analytical organizations Foreign Affairs Maidan and Informnapalm, who were working from open source shipping data and information collected on social networks. Based on their investigation, the current location of these rigs is likely about 12 nautical miles from Crimea. Most probably, they are being guarded by soldiers of the 126th Coastal Defense Brigade of the Russian Black Sea Fleet (Informnapalm, January 25).

Moscow estimates the value of the two Chornomornaftogaz rigs to be $354 million (TASS). Thus, Russia is proactively depleting Ukrainian energy assets: the estimated extraction from the offshore Odesa natural gas field deposit measures 1.17 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year, or 57 percent of the annual gas output in Crimea. Its location, 150 km west of annexed Crimea, allows Moscow to claim the field as part of Russia’s exclusive economic zone, thus questioning Ukraine’s sovereignty over the gas field (Kommersant, December 15, 2015).

Ukraine is suing Russia over its annexation of the Odesa gas field and other Crimean and Black Sea assets in a Stockholm arbitration court. But future disputes are likely to be over the even larger Pallas gas and oil field, located in the northeastern sector of the Black Sea, between the borders of Russia and Ukraine. Russia began courting Ukraine into joint drilling of the Pallas field with Gazprom since 2003 (Rosbalt, September 17, 2003). After lengthy negotiations, then-president Viktor Yanukovych’s administration agreed to a joint venture with Gazprom and Lukoil, in December 2010 (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, January 25, 2011). Russian interest in the Pallas field was so high that energy ministers of both countries even discussed the issue days before Yanukovych fled Ukraine (RT, February 1, 2014).

All this notwithstanding, bilateral Ukrainian-Russian disputes over offshore gas and oil fields are unlikely to reach the level of full military confrontation anytime soon. This is due to a variety of reasons: from current low hydrocarbon prices, to uncertainty about whether Ukraine will be able to secure a favorable ruling in the international arbitration process. Nonetheless, another possible role for Russian naval forces in the region may be to disturb commercial maritime flows across the Black Sea. This would diminish the recent initiative of the Baltic States, Ukraine and Georgia to establish a Russia bypass trade route to China, which includes a Black Sea marine shipping leg from Ukrainian to Georgian ports (see EDM, January 27).

The naval and FSB escort provided for the two Ukrainian-owned drilling rigs that were hijacked by Russia last December clearly indicates that Moscow had prepared for the possibility of a forceful response by Ukrainian vessels in the area. Indeed, in summer 2015, the Ukrainian flagship frigate Hetman Sahaidachniy reportedly forced a Russian ship out of Ukraine’s territorial waters (Glavcom.ua, June 6, 2015). Yet, Russia does not seem at all concerned that Ukraine might try to hamper gas extraction operations in the Odesa field by the recently installed Tavrida drilling platform. Ukrainian Admiral (ret.) Ihor Kabanenko told this author, on January 10, that Ukraine’s navy effectively controls essentially only its littoral waters. It has little access to Ukraine’s extended exclusive economic zone—in which the Odesa field legally lies. Russia, on the other hand, has been quite active throughout the Black Sea. In fact, last December, the Russian military escort accompanying the two aforementioned Chornomornaftogaz rigs forced a vessel flying the Turkish flag to change the course away from the transport convoy (TASS, December 14, 2015).

It is likely that the rig removal operation—complete with a Black Sea Fleet escort—may also have had a deliberate informational component, perhaps signaling a warning to the US in response to its naval cooperation with Ukraine in the Black Sea. The timing of the incident was conspicuously within days of the December 10 reports of USS Ross conducting a passing exercise with a Ukrainian ship (Facebook.com/USNavalForcesEuropeAfrica, December 10).

Alliance members, including Romania, have called for strengthening NATO capacities in the Black Sea; thus, US policy is presently focused on supporting its regional allies through exercises and a persistent naval presence (New Europe, January 19). It is unclear, what US and NATO strategy would be were Russia to initiate a maritime military conflict with Ukraine, or simply even interfere with NATO members’ or Georgia’s Black Sea commercial shipment lanes and energy projects. But clearly, Russia firmly wants to gradually reduce US and NATO influence in this strategically important region.