Sino-Australian Relations and the Bumpy Road to the G7 Summit

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 10

By:

Introduction

The Chinese-born Australian journalist Cheng Lei (成蕾) was formally arrested by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in early February after having been detained for six months in Beijing. Her arrest was confirmed by the PRC on February 8, with Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin (汪文斌) stating that Cheng would face criminal charges for “illegally providing state secrets to foreign forces,” and that Chinese judicial authorities would “handle the case in accordance with law and fully protect her rights” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 8). China’s criminal conviction rate is above 99.9 percent (China Justice Observer, November 16, 2020). According to a statement issued by Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne, “The Australian Government has raised its serious concerns about Ms. Cheng’s detention regularly at senior levels” (Foreignminister.gov.au, February 8) and Australian Embassy officials have visited Cheng regularly since her detention in August.

Background

Cheng’s arrest comes amid strained diplomatic ties between China and Australia that have carried over from last year, with tensions rapidly escalating after Foreign Minister Payne’s call in April 2020 for an international investigation into the origins and spread of the coronavirus pandemic (Australian Foreign Minister, May 18, 2020). Australian-Chinese bilateral trade was heavily impacted by the deteriorating political relationship and trade issues continue to dominate in the ongoing feud. End of year statistics from the PRC General Administration of Customs (GAC, 中华人民共和国海关总署, zhonghua renmin gongheguo haiguan zong shu) showed that China’s imports of Australian goods declined by 5.3 percent year-on-year in 2020, compared to a year-on-year increase of 14.8 percent in 2019 (GAC, January 14, 2020; January 14).

This decline should have been worse; the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that soaring iron ore prices at the end of 2020 saw Australia’s export of metalliferous ore to China actually increase by 25 percent in December 2020, boosting overall exports (ABS, January 25). In 2021, Australian exports of metalliferous ore to China fell by 12 percent in February and rose by 15 percent in March. China accounted for 75 percent of all Australian iron ore exports in the March 2021 release of trade statistics, boosting total exports by 2 percent year-on-year (ABS, March 24). It’s worth mentioning that these numbers could potentially understate the impact of the trade dispute on the Australian economy in the long-term; as will be discussed later in this article, China has been working to diversify its key imports from Australia, including liquid natural gas (LNG) and coking coal (SCMP, May 12; World Coal, February 10).

Cheng’s arrest, in combination with this year’s preliminary trade and people-to-people statistics, provides hard evidence of the ongoing deterioration in Sino-Australian relations beyond the headline-making political disagreements. This article takes a detailed look at the numbers underlying the bilateral relationship to analyze how recent developments could preclude further decline or improvement in the second half of 2021.

A Loss of Media Presence Amid Weakening Diplomacy

Following the start of diplomatic relations in 1972, Sino-Australian relations emphasized cordial and constructive engagement for decades: Australia’s abundant natural resources fuelled China’s rapid economic growth, and China’s growing consumption of luxury goods boosted Australia’s economy in return. At the same time, Australia’s increasingly close ties to the United States following the end of the Cold War have led it to be a staunch defender of the liberal world order, which China has increasingly sought to reshape.

In general, Australia follows the U.S. approach to China; Canberra’s security concerns in the Indo-Pacific in particular are closely tied to Washington’s policy, and its state identity more broadly is intrinsically linked to the values of liberal democracy.[1] As American perceptions of China as a “strategic competitor” have solidified, Australia also increasingly views China’s rise as something to resist. This attitude has seen Australia enthusiastically (re)commit to the revived Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with the U.S., India and Japan; ban the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei from participating in national 5G networks; enact foreign interference laws widely seen as aiming to counter Chinese influence and accelerate its $1 billion AUD ($762,540,000) U.S.-assisted Sovereign Guided Weapons Enterprise to counter China’s security manoeuvres in the Indo-Pacific.

Before her arrest, Cheng was a success story for Australian soft power inside the PRC; she was a famous presenter on the state-affiliated China Global Television Network (CGTN, 中国环球电视网, zhong guo huan qiu dian shi wang) and a self-proclaimed “passionate orator of the China story” (China Digital Times, August 31, 2020). Following her abrupt disappearance in August 2020, the Australian journalists Bill Birtles and Michael Smith were questioned by state security services in connection with the Cheng Lei case, prompting them to leave the PRC in September 2020. (ABC, September 7, 2020).

Today, Australia no longer has an accredited media presence inside China for the first time since 1973, marking the end of a key channel for engagement amid rapidly declining state relations. The Sydney Morning Herald’s Eryk Bagshaw argues that the loss has visibly hurt the quality of Australian reporting on China: “Chinese propaganda voices are being elevated…the weight of coverage has shifted to the economic consequences of Australia’s policy decisions and there is limited visibility” of domestic Chinese issues (Sydney Morning Herald, May 3).

Education Migration ‘Down Under’ Less Attractive

Bilateral ties had been supported by decades of strong Chinese immigration to Australia. According to the latest census data, around half a million China-born people lived in Australia in 2018.[2] But Australia’s longstanding attraction to Chinese migrants has rapidly waned; amid the deteriorating diplomatic relations, both sides have issued travel warnings about the risks of traveling to each other’s countries (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Smartraveller, February 9; PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs Consulate Service, July 13, 2020). Additionally, harsh pandemic border restrictions have effectively frozen travel to Australia, further stymieing tourism, education, and other people-to-people ties.

According to the Australian Department of Education, 211,965 of the 765,636 students studying in Australia in 2019 were of Chinese nationality, but these numbers fell by 10 percent over the course of 2020. Even after this change, Chinese students still made up more than a quarter of all students studying in Australia (Internationaleducation.gov.au [1], [2], accessed May 13). But amid potential rising anti-Asian hate in Australia, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has discouraged its citizens from studying in Australia. The PRC Ministry of Education released a statement on February 5 warning of anti-Asian discrimination and “successive vicious incidents” against Chinese students in Australia, and urged Chinese students to “fully conduct safety risk assessments” before traveling to Australia (PRC Ministry of Education, February 5).[3] The ABS has reported that Chinese citizens were the largest group departing Australia in January, February and March this year, with slightly over a fifth of all international departees on temporary student visas (ABS, April 20, March 17).

One recent study found that Australia’s strong Chinese student population supported 259,199 full-time local jobs in 2018.[4] The negative trend in Sino-Australian educational exchanges will have a major economic impact. So long as Sino-Australian relations continue to decline, it seems unlikely that this situation will improve. According to a report this year issued by a Chinese education consulting company, Chinese students are increasingly preferring to study abroad in the United Kingdom (UK) or the U.S. over Australia (EIC Education, March 25).

Toward Re-coupling or Further Diversification?

As mentioned earlier, the Australian economy took a significant hit as relations with China declined in 2020. China reduced Australian imports of beef, barley, cotton, copper, coal, timber and wine last year, among others.[5] High iron ore prices combined with China’s strong demand mitigated what would have otherwise been poor bilateral trade figures in 2020.

By the mid-point of 2021, China’s efforts to reduce its dependence on critical energy supplies from Australia appear to have had limited success. Even as China doubled its year-on-year imports of LNG from Russia up to 5.1 million tons in 2020, 43 percent of China’s imported LNG continued to come from Australia.[6] But in January and February just 35 percent of China’s LNG imports came from Australia,[7] and the CCP has made the further diversification of energy sources a key priority in its 14th Five Year Plan (FYP, 2021-2025) (PRC Ministry of Commerce, January 28; Xinhua, March 13).

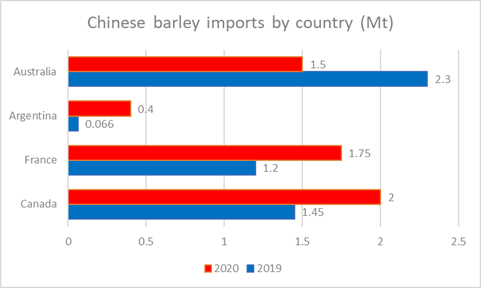

China’s diversification of non-energy commodities such as barley has been more successful. After an 80.5 percent anti-dumping duty was imposed on Australian barley imports in May 2020, the grain all but stopped reaching Chinese shores (SCMP, November 17, 2020). China’s barley imports from Canada, France and Argentina all increased significantly last year, with year-on-year gains of 38 percent, 46 percent and 490 percent respectively in 2020.[8] Canberra’s decision in December 2020 to appeal China’s barley tariff at the World Trade Organisation will likely incentivize China to continue diversifying its sources of the grain.

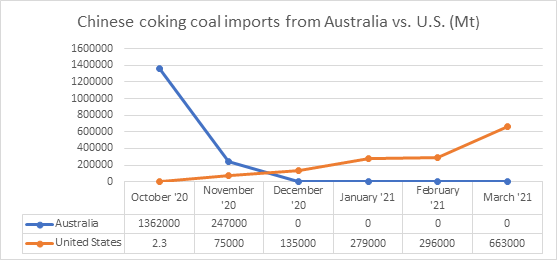

China has also worked to diversify its sources of coking coal since unofficially banning Australian imports in October 2020.[9] While China can produce sufficient amounts of thermal coal for its domestic power generation needs, it imports the majority of the higher quality coking coal used in steelmaking. American imports have seen a large surge, with 575,000 tons sold to China in January and February, an increase of 550 percent from the same period last year.[10] This trend will likely continue as China looks to diversify coking coal sources away from the Australian market and meet its target of importing an additional $52.4 billion worth of energy products from the U.S. by the end of 2021 under the U.S.-China Phase One trade deal signed in January 2020 (USTR, January 15, 2020). Even though Chinese iron ore imports over the last year have led to what one analyst recently called “one of the most incredible transfers of wealth between the pockets of the Chinese and Australian government” (SCMP, May 18), China’s interest in the Simandou mine in south-eastern Guinea, which holds an estimated 2.4 billion tons of medium to high grade iron ore, should worry Australian politicians: access to the reserves would lessen China’s reliance on Australian iron, taking away a source of leverage that has so far remained steady (Mines.gov.gn, accessed May 18).

There are rare signs for improving Sino-Australian trade in 2021. Following the upgrade of a 2008 free trade agreement (FTA) between China and New Zealand on January 26, Australia was also given the opportunity to expand upon its existing FTA with China, although nothing has come of this so far (SCMP, January 26). Additionally, following the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) on November 15, 2020 and China’s ratification of the deal during annual legislative meetings in March (Xinhua, March 8), Australia is expected to ratify the deal in late 2021 (DFAT, accessed May 18). Doing so could send a strong signal about Australia’s willingness to prioritize its economic relationship with China over political disagreements.

Other signs are grimmer. Despite some hopes for a reset in trade relations from the new Australian Trade Minister Daniel Tehan in January, the two sides have so far failed to hold high-level talks (ABC, January 22). China’s decision to officially impose import duties between 116.2 and 218.4 percent on certain Australian wines at the end of March led the Australian Ambassador to China Graham Fletcher to label China an “unreliable … trading partner” (SCMP, The Australian, 26 March). In late April, Foreign Minister Payne announced Australia’s decision to end a Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) memorandum of understanding between the Victorian state government and China. The Chinese Embassy in Australia expressed its “strong displeasure” at the decision, while the Chinese state media agency Xinhua called this a “stark disregard for the spirit of contact [that] has put Australia’s credibility into question” (PRC Embassy in Australia, April 21; Xinhua, April 22). About two weeks later, China’s powerful National Development and Reform Commission announced that it had decided to “indefinitely suspend all activities” under the framework of the China-Australia Strategic Economic Dialogue (PRC Embassy in Australia, May 6).

Conclusion

At the beginning of this year, the Morrison government began to openly speak of its desire for constructive engagement with China, and Chinese officials also echoed this desire (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs December 18, 2020; Prime Minister of Australia February 1). At the same time, diplomatic spats have continued, and both sides have failed to take advantage of opportunities for improving engagement even as China has begun to diversify some of its most critical imports from Australia. In addition to reports of growing anti-Chinese racism, Sinophobia is also rife within Australian politics: after cancelling Victoria’s BRI agreement, the Australian government has begun reviewing a Chinese company’s 2015 lease agreement on the Port of Darwin (SCMP, May 4). High-level national security officials have increasingly warned of a possible military confrontation with China, even as Foreign Minister Payne said this week that Australia is ready to resume dialogue with China “at any time” (ABC, April 26; Sydney Morning Herald: May 3, May 14).

Australia, along with South Korea and India, has been invited to attend the upcoming Group of Seven (G7) summit in June, hosted by the UK. European members, particularly France and Italy, have argued against these invitations, saying that they do not want the G7 to turn into a broad ‘anti-China’ coalition (Global Times, February 10). China has previously indicated its sensitivity toward expanding the grouping (China Brief, March 25). Regardless, topics concerning Chinese economic coercion, labor violations, forced technology transfer, etc. will likely be discussed at the summit. The event could provide a highly visible opportunity for the Morrison government to demonstrate that Canberra is ready to make concrete actions toward rapprochement in 2021. More likely, it will serve as a staging ground for Australia to publicly criticize China amongst its democratic peers and signal to Beijing that Canberra is not prepared to actively repair Sino-Australian ties, something that would ensure relations continue to deteriorate in 2021.

Patrick Triglavcanin is an Australian freelance research assistant and writer and Master’s researcher. He has been published by the Australian research institute Future Directions International and London-based think tank the Fabian Society.

Notes

[1] This strategic alignment has led nationalistic Chinese commenters such as the state tabloid Global Times to frequently refer to Australia as America’s “pawn” (爪牙, zhaoya) and “attack dog” (Global Times, May 15, 2020; December 9, 2020).

[2] See: “China-born Community Information Summary,” Department of Home Affairs, 2018, https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-china.PDF.

[3] For potential rising anti-Asian hate in Australia, see: Natasha Kassam and Jennifer Hsu, “Being Chinese in Australia: Public opinion in Chinese communities,” Lowy Institute, March, 2021, https://interactives.lowyinstitute.org/features/chinese-communities/topics/who-did-we-survey.

[4] James Laurenceson and Michael Zhou, “COVID-19 and the Australia-China Relationship’s Zombie Idea,” ACRI University of Technology Sydney, May, 2020, pp. 9, https://www.australiachinarelations.org/content/covid-19-and-australia-china-relationship%E2%80%99s-zombie-economic-idea.

[5] For discussions of the China-Australia trade dispute, see: Scott Waldron and Zhang Jing, “Chinese Tariffs on Australian Wine in 2020: The Domestic Drivers of International Coercion,” Future Directions International, February 23, 2021, https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/chinese-tariffs-on-australian-wine-in-2020-the-domestic-drivers-of-international-coercion/; Greg Hull, “Too Many Eggs in the Dragon’s Basket? Part One: Australia’s Reliance on Exports to China,” Future Directions International, October 27, 2020, https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/too-many-eggs-in-the-dragons-basket-part-one-australias-reliance-on-exports-to-china/; Greg Hull, “Too Many Eggs in the Dragon’s Basket? Part Two: Australia’s Reliance on Exports to China,” Future Directions International, January 21, 2020, https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/too-many-eggs-in-the-dragons-basket-part-two-diversifying-australias-export-base-2/; Saheli Choudhury, “List of the Australia exports hit by restrictions in China,” CNBC, December 17, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/18/australia-china-trade-disputes-in-2020.html.

[6] This statistic has been calculated by the author using figures provided by the PRC General Administration of Customs (中华人民共和国海关总署, zhonghua renmin gongheguo haiguan zong shu).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.