The Stable Door and Chollima: Chinese Computers and North Korean IT

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 16

By:

In early 2016, Chinese border authorities reportedly cracked down on exports to North Korea due to irritation over Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons and missile tests. Despite these and previous sanctions, computers and electronics appear to be freely available in Pyongyang. Such electronics play a vital role in enhancing the strength of the North Korean state, in particular its own cyber capabilities and advanced weapons programs. The flow of chips and other electronic components, an obvious target for Chinese assertion of economic influence over North Korea appears to have been largely ignored. It seems, in short, that China has let the proverbial horse bolt out the stable door: over the past decade, increasingly fast computing became available to the Pyongyang regime. North Korea may already have developed an IT sector sophisticated enough to help design, make and test nuclear weapons and missiles—and even the supposed PRC export crackdown appears to have been temporary. [1]

How did Pyongyang acquire advanced computing over the past decade? Several possible pathways for these sales are apparent, notably the hundreds of independent Chinese distributors of Western CPUs and computers. A thorough assessment of the impact of such imports would require close examination of the records of these U.S. and other companies and their Chinese distributors, but could be accomplished with carefully planned U.S.-China cooperation.

Defining North Korean Computing and IT

A CIA analyst observed ten years ago that Pyongyang employed a small number of analysts to seek open source intelligence on the Web. Evidence suggests that the North Korean IT sector has expanded rapidly since then. [2] Well-known Dutch consultant Paul Tjia, who promotes trade with Pyongyang, estimates the isolated country has perhaps 10,000 IT professionals at work with more graduating each year from several institutions. In 2010–12, Tjia observed that North Korean IT professionals appeared usefully employed by foreign partners in unexpected ways, some working for joint ventures like Nosotek (NK-German) and Hana Electronics (Youtube, August 25, 2009; NKnews, September 9, 2015). [3] Tjia also noted North Korean companies with outsourcing contract partners in Europe, Japan, and South Korea, in the fields of graphic design, cartoon and animation work (Pyongyang SEK, April 6). North Korean firms even contract to write software for IT security and access control systems (ACM, August 2012; IEEE.org, September 2012). Mr. Tjia is still at work: in September of this year, he led a European trade mission to Pyongyang seeking budget IT work, among other deals (gpic.nl )

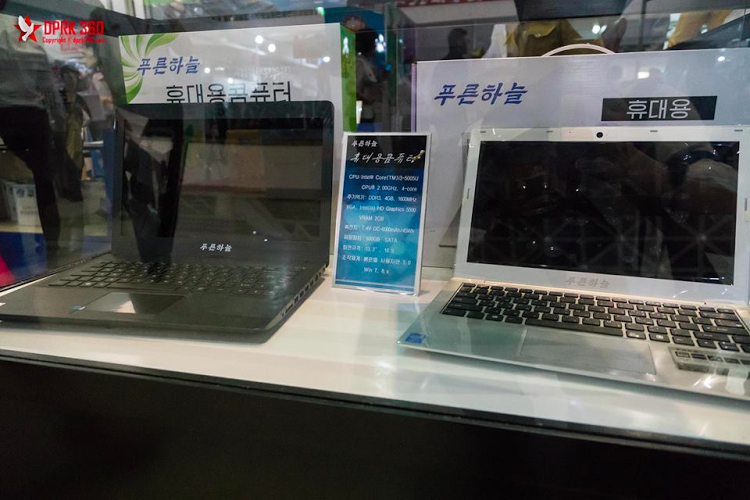

Though overall North Korean imports from China dropped in January of this year, they surged higher in August (KEI, October 4). However complicated the big picture, it is clear that computers have entered North Korea in increasing quantities in the past decade, and still are doing so (table 1). Specifically, advanced laptops with U.S.-made CPUs were observed at the Pyongyang Spring Trade Fair in May—albeit for lower prices and probably in lower quantities compared to neighboring China (photos below). North Korean-“Blue Sky” brand desktops (푸른하늘, Purun Hanul, a China-NK joint venture) with American made I3 and I5 CPUs were also observed at the show (DPRK360.org, May 2016). In ordinary public institutions, older Dell desktops with 486 to Pentium architecture have also been observed (IMD, April 5).

English class, Pyongyang Library, March 2016. The teacher controlled presentations with a desktop, and about 20 older Dell desktops were visible in an adjacent room. Photo courtesy Professor Arturo Bris, IMD Switzerland.

Kim Jong Il views a Dell monitor and desktop in 2010 at the Hamhung University of Chemical Engineering (Freerepublic.com, May 2010)

North Korea’s very active missile and nuclear weapons development programs and its developed cyber infrastructure all point to increasing reliance on advanced computing capabilities. [4] Any serious effort to interrupt Pyongyang’s efforts in these areas should include an examination of how computers reach the regime, and a reevaluation to improve relevant trade controls.

Lips and Teeth: Dandong-Sinuiju-Pyongyang

Chinese organizations are reported to have 167 supercomputers of the world’s top 500, compared to 165 in the US. Almost all of China’s Tianhe series machines are powered by U.S.-made CPUs, though the latest and fastest reportedly, the Shenwei, (神威, aka: Sunway TaihuLight) supposedly only uses domestically-produced parts. The processors at the heart these supercomputers are multicore CPUs arranged in parallel—yielding the kind of number crunching power needed to forecast the weather, create and attack communications ciphers, simulate nuclear bomb blasts, and design missiles, among other things (PCWorld, TheNextPlatform, and phys.org, June 20).

UN Security Council Resolution 2270, to which China agreed, prohibits the transfer to North Korea of computers and IT equipment that could contribute to nuclear weapons development. [5] Of concern to American companies and other firms dealing in U.S.-made components is preexisting American law, the Export Administration Act, controlling almost all sales to North Korea other than medicines and food. [5] Despite UN and U.S. controls, the goods still go there. Many roads lead to Pyongyang, as underlined by the activities of North Korean operatives who comb the world for luxury goods in the service of Kim Jong Un’s “gift politics” (Youtube, May 2014). But the easiest and shortest path for computers entering North Korea is likely through the Chinese border metropolis of Dandong.

Just 900 meters across the Yalu River from the North Korean town of Sinuiju, Dandong must seem like a wonderland of lights and a cornucopia of goods. Besides Dandong’s restaurants, bars, well-stocked grocery outlets, and department stores, the city boasts a large number of North Korean “trade representatives,” large and small, and 15–20,000 North Korean workers in Chinese-managed factories. Over 80 percent of North Korea’s imports come from China, and two thirds or more of North Korea’s entire foreign trade passes through Dandong (OEC, 2013; nknews.org, September 28). At different times in 2016, a more restrictive regulatory atmosphere in the Chinese city supposedly made open discussions on commerce, especially computer sales, difficult (finance.sina.com, April 1). However, besides overall trade, Chinese statistics show that PRC computer exports to North Korea have again resumed, and are higher than previous times (table 1), just as concerns have arisen that PC sales in China may soon decline (Wall Street Journal, January 15).

Table 1. Source: PRC statistics via William Brown, “China’s North Korea Trade Surges in August,” in “The Peninsula, 4 October 2016

Although the North Korean market is small in comparison to China, high-end laptops appear to be bound for Pyongyang with little if any restriction. Multiple methods to ship cargo from China to North Korea are available, prominent among them the Chinese State Postal Bureau, aka: China Post, according to an experienced logistics executive (Author Interview, October). But what about more powerful servers, and even parallel processor supercomputers, that could assist in North Korean weapons development?

Recent information indicates that North Korea’s “private intranet,” the Kwangmyong (광명; 光明) network, has just 28 websites, the servers for which could be in North Korea or China (UK Telegraph, September 21). Its existence therefore provides no hint about high-end computing in North Korea, because websites like those visible on Kwangmyong could be hosted on a laptop and could easily be based in China itself. However, North Korean missile and nuclear development efforts would likely be a magnet for the multi-CPU servers and more powerful parallel supercomputers readily available in China.

The secretive nature of nuclear and missile development work makes analysis difficult with currently available data. However, given the critical nature of proliferation concerns, giving up does not seem like an acceptable option.

Conclusion

Both the U.S. and Chinese governments profess interest in slowing or stopping North Korea’s nuclear program (Folkw.cn, September 24). The two governments have the authority to examine relevant sales records of U.S. and other companies that make the CPUs and computers observed in North Korea, their Chinese distributors, and Chinese joint venture partners with Pyongyang. A joint examination by China and the U.S. would begin to shed light on the current situation: how many advanced laptops and desktops are in North Korea? How many machines are dedicated to civilian end-use? Is there information that points to military end-use? Are there indications of supercomputer use in North Korea? Would the harvest of such data allow analysts to refine projections about the future of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs?

At a time when the PRC and the U.S. seek areas of cooperation, this problem offers an opportunity to accomplish something substantial that would serve the interests of both nations.

Matthew Brazil is a non-resident Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation. He has worked in Asia as a soldier, US diplomat and a corporate security manager. With Peter Mattis, he is the co-author of an upcoming work on Chinese intelligence operations.

Notes

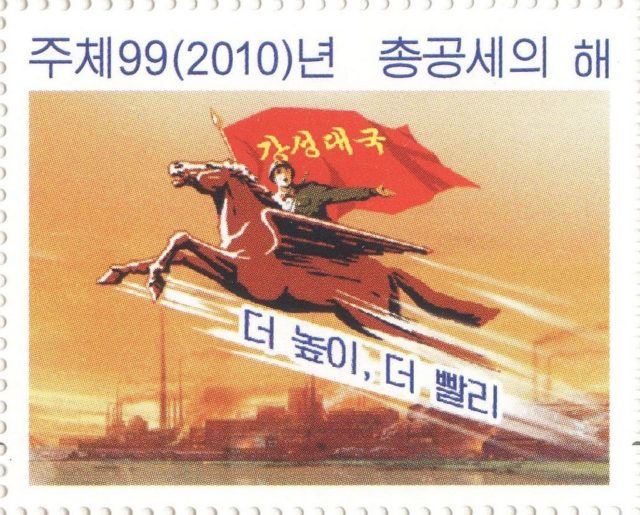

- Kim Il Sung launched the Chollima (천리마, 千里马) Movement in December 1956 to spur self-directed worker enthusiasm. The winged horse that can travel 1000 li in a single day remains a symbol of North Korean determination to catch up to the rest of the world in industry and technology. Hy-Sang Lee, North Korea: A Strange Socialist Fortress (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), pp. 27-28.

- Stephen Mercado, “The Hermit Surfers of Pyongyang”, June 27, 2008

- GPI Consulting < https://www.gpic.nl/en/>

- Jenny Jun, Scott LaFoy, and Ethan Sohn, “North Korea’s Cyber Operations” CSIS, December 30, 2015, pp. 5–7.<https://www.csis.org/analysis/north-korea%E2%80%99s-cyber-operations>

- Measure 17 in UN Security Council Resolution 2270, dated March 2, 2016, prohibits “teaching or training in advanced physics, advanced computer simulation and related computer sciences” if it could assist in North Korea’s nuclear program.

- Part 746.4 of the US Export Administration Regulations and the country specific guidance on exports to North Korea require an U.S. Individual Validated License for exports or re-exports to North Korea except for food and medicines. This would include computers.