‘Strait Thunder-2025A’ Drill Implies Future Increase in PLA Pressure on Taiwan

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 7

By:

Executive Summary:

- People’s Liberation Army (PLA) operations against Taiwan on April 1–2 consisted of multiple drills that had limited interconnection, distinguishing them from exercises that tend to be more complex and confrontational.

- Recent training reforms have meant that drills now tend to involve more cross-service coordination and are likely to match the scale of military exercises. The “Strait Thunder-2025A” drill is evidence of this trend, as its scale is comparable to past “Joint Sword” exercises.

- “Strait Thunder-2025A” exhibited a new focus on chokepoint control with the emergence of a dual-layer “Cabbage Strategy,” in which an inner circle of maritime militia, coast guard, and naval forces surrounds Taiwan while a separate outer circle harrasses foreign military forces.

- The name of the drill, “Strait Thunder-2025A,” suggests that the PLA is likely to conduct additional such drills this year. It also hints that future exercises could exceed the scale of previous Joint Sword military exercises.

On April 1, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Eastern Theater Command announced a joint training drill (联合演训) around Taiwan. The next day, it declared the initiation of the “Strait Thunder-2025A Drill” (海峡雷霆-2025A演练) (Xinhua, April 1, April 2). According to data from Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense, over the course of these two days, the PLA deployed 135 aircraft, 38 naval vessels, and 12 official vessels in the surrounding area.

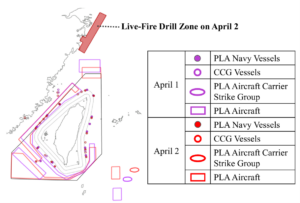

Strait Thunder-2025A was a routine large-scale training drill. The PLA has conducted such activities with increasing frequency in recent years and, as indicated by the “A” in the drill’s title, will continue to do so in the near future. The scope of military activities during the recent drill is depicted in Figure 1 (Ministry of National Defense, April 2, April 3; LTN, April 1, April 2). Numerous reports and analyses have focused on the strategic or political considerations behind the PLA’s military actions, as well as the logic behind the naming of the operations (CNN, April 1; CNA, April 1, April 2; Global Times, April 2; The Guardian, April 2). However, few have examined the military implications of these actions themselves.

Figure 1: PLA Military Activities Around Taiwan From April 1 to April 2

(Source: Compilation by authors based on press releases from ROC MND and PRC Maritime Safety Administration)

Strait Thunder-2025A: A Drill, not an Exercise

The PLA’s Chinese-language press releases described the recent military activities as a “training drill” (演训) and a “drill” (演练). The headline of Xinhua’s first article on April 1 used the term “joint training drill” (联合演训), and the content referred to it as a “drill” (Xinhua, April 1). On April 2, Xinhua’s press release announcing “Strait Thunder-2025A” also used the term “drill” in both the headline and the content (Xinhua, April 2).

There is a clear distinction between a “drill” and an “exercise” in Chinese military terminology. According to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Military Terms (中国人民解放军军语), a “drill” (演练) refers to an activity that simulates the process or specific parts of military operations or other military actions under certain rules and scenario-induced conditions and typically is organized by a small number of directing and coordinating personnel. Drills are usually used for training squad-level (分队) personnel. In contrast, an “exercise” (演习) is an operation or action drill conducted by troops under the organization of an “exercise director department” (导演部) and under scenario-induced conditions (i.e., adjusting scenarios based on the exercise’s progress and real-time developments). [1] As this suggests, the main difference between a drill and an exercise lies in the presence of the latter with an exercise director department and in the number of personnel involved in “directing and coordinating” (导调) the event. The exercise director department is a temporary organization responsible for planning and organizing military exercises. It provides guidance and control over the exercise, including directing, inspecting, adjudicating, evaluating, and collecting data on the participating forces. Under this definition, drills are also typically carried out entirely according to plan; only exercises may involve the introduction of ad hoc scenarios or the presence of an opposing force. This is because the exercise director department is required to provide the directing and coordinating personnel needed to manage such complex activities.

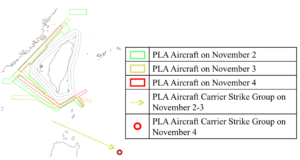

Figure 2: PLA Activities, November 2–4, 2024

(Source: Compilation by authors based on press releases from ROC MND and Japan’s Ministry of Defense Joint Staff)

The PLA’s military actions around Taiwan on April 1–2 do indeed appear to have been a series of drills, as official coverage claimed. They consisted of various discrete training activities with minimal connection between them, thus falling short of the complexity associated with an exercise. For instance, the aircraft activities during this drill did not reflect a realistic combat scenario. PLA aircraft crossed the Bashi Channel into the Western Pacific, including at least one H-6 bomber equipped with an air-launched anti-ship YJ-21 missile, according to footage released by the PLA (Global Times, April 1). Subsonic aircraft like the H-6 would struggle to safely traverse this route in an actual combat scenario, which likely explains why such patterns did not occur during the three Joint Sword exercises in 2023–2024 (China Brief, November 1, 2024). The April drill also exhibited activities similar to those that occurred during other non-exercise periods. For instance, on November 2–3, 2024, PLA aircraft also crossed the Bashi Channel and flew east into the Western Pacific for drills, while the Shandong Carrier Strike Group also entered the Western Pacific from the waters between Taiwan and the Philippines before returning to the South China Sea after November 4 (Ministry of Defense, November 5, 2024; Ministry of National Defense, November 3, 2024, November 4, 2024, November 5, 2024; RW News, November 1, 2024). (See Figure 2).

The actions of the Shandong Carrier Strike Group during Strait Thunder-2025A also support the assessment that it was a drill, not an exercise. It did not serve as a mock enemy but instead focused on the PLA’s own regional control training. According to PRC state media, the carrier group conducted joint ship-aircraft coordination, regional air dominance, and strikes against sea and land targets in the Western Pacific (Xinhua, April 2). The aircraft that flew out of the Bashi Channel did not head toward the carrier group but instead moved north, operating in the waters east of Taiwan, as shown in Figure 1 (Ministry of National Defense, April 2; April 3). This differs significantly from the activities in early November 2024.

The actions of the artillery element further support this assessment, as demonstrated by the live-fire drills conducted by the Eastern Theater Command’s ground forces off the coast of Zhejiang Province. Although PRC state media reported that the live-fire drills were part of the overall operation, they did not take place in the vicinity of Taiwan, reinforcing the notion that the activities were simply an independent drill of its specific objectives, as shown in Figure 1 (Maritime Safety Administration, April 1; Xinhua, April 2). [2]

Drill Focused on Control of Key Areas and Chokepoints

The drill had three observable features that are worthy of analysis. These were its large scale, unusual level of complexity for a drill, and focus on seizing control of key areas and chokepoints.

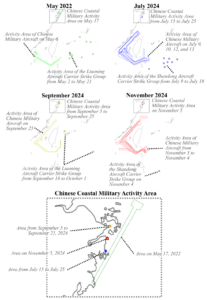

The scale of this drill rivaled that of past large-scale exercises targeting Taiwan, as is clear from a comparison of the number of aerial sorties and naval vessels involved (see Table 1). This is a departure from earlier drills, which typically involved training for single units or small-scale operations—well below the scope of exercises (China Aerospace Studies Institute, October 25, 2021). The drill primarily involved an aircraft carrier group, a large number of naval and air forces, aircraft flying to the Philippine Sea, and live-fire exercises by the Eastern Theater Command along the PRC coast. Similar activities have occurred at least four times since 2022, specifically in May 2022, July 2024, September 2024, and November 2024 (see Figure 3 and Table 2). The most recent drill was larger in scale than any of these four previous drills.

The unusual scale of this drill is in part a function of its complexity, which involved simultaneous land, sea, and air operations—something that was not the case for the four previous drills. This reflects the PLA’s increased emphasis in recent years on cross-unit and multi-service participation in its training. In 2020, General Secretary Xi Jinping highlighted the need to accelerate the development of a new military training system during the Central Military Commission’s military training conference (中央军委军事训练会议) (Xinhua, November 25, 2020). In 2023, the PLA held an on-site conference on basic training (全军基础训练现场会) at which it announced plans to accelerate innovations in basic training methods, including instituting intensified training by breaking down unit boundaries and conducting basic training across units (Xinhua, June 21, 2023; PLA Daily, July 10, 2024). In 2024, the PLA convened an on-site conference on combined training (全军合成训练现场会), declaring its intent to explore new models for combined training with a focus on establishing cross-service and cross-branch training (People’s Daily, October 23, 2024; PLA Daily, December 2, 2024, December 5, 2024). As a result of this shift, training or drills now focus on integration across services and branches. The push for more integration also means that drills can occur on a similar scale to exercises. The crucial difference between the two, however, may remain the distinction over whether a maneuver involves complex scenarios or ad hoc operational directives.

Table 1: Recent Large-Scale PLA Exercises and Drills Targeting Taiwan

| Exercise or Drills | Date | Sorties Crossing the Median Line | Detected Sorties Around Taiwan | PLA Naval Vessels | Official Vessels |

| 2022 Drill | August 4 | 22 | |||

| August 5 | 49 | ||||

| August 6 | 20 | 20 | 14 | ||

| August 7 | 22 | 66 | 14 | ||

| 2023 Exercise | April 8 | 45 | 71 | 9 | |

| April 9 | 35 | 70 | 11 | ||

| April 10 | 54 | 91 | 12 | ||

| 2024A Exercise | May 23 | 35 | 49 | 19 | 7 |

| May 24 | 47 | 62 | 27 | ||

| 2024B Exercise | October 14 | 111 | 153 | 14 | 12 |

| 2025A Drill | April 1 | 37 | 76 | 15 | 4 |

| April 2 | 31 | 59 | 23 | 8 |

(Source: Compilation by authors based on reporting from Xinhua and press releases from ROC MND)

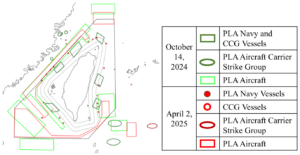

A primary focus of the drill in April was on “key area and chokepoint control” (要域要道封控). For example, the Bashi Channel between Taiwan and the Philippines is a chokepoint for entry and exit to the South China Sea (People’s Daily, August 6, 2022). According to Professor Zhang Chi (张弛) of the PRC’s National Defense University, during the drill, the PLA created a strong maritime barrier through chokepoint control with its aircraft carrier strike groups, creating external obstruction and internal pressure or isolation aimed at preventing interference from external forces (Global Times, April 2). Troops were deployed to chokepoints around Taiwan and were also dispersed across more distant maritime and airspace areas, as shown in Figure 4. This included an aircraft carrier group operating farther from Taiwan than during the Joint Sword-2024B period, China Coast Guard (CCG) vessel 2302 operating more than 100 nautical miles east of Taiwan, and three Chinese fishing vessels—suspected to be part of the PRC’s maritime militia—conducting activities 140 nautical miles off the coast of Hualien Harbor in eastern Taiwan in coordination with the CCG (Up Media, April 2; Youth Daily News, April 2). These deployments contrasted with those during Joint Sword-2024B, which concentrated on a blockade of important ports and areas (要港要域封控). This highlights the PLA’s focus on practicing control over Taiwan’s surrounding maritime chokepoints.

Table 2: Comparison of the Scale of This Drill With Previous Similar Drills

| Dates of Aircraft Carrier Operations | Chinese Coastal Military Activity | The Size of the Areas

(km2) |

Dates of PLA Aircraft Flying From the Bashi Channel to the Philippine Sea | Sorties Crossing the Median Line | Detected Sorties Around Taiwan | PLA Naval Vessels | Official Vessels |

| May 2 to May 21, 2022 | May 17 | 3,281 | May 6 | 18 | |||

| July 9 to July 18, 2024 | July 15 to July 25 | 17.9 | July 9 | 26 | 35 | 8 | |

| July 10 | 56 | 66 | 7 | ||||

| July 12 | 20 | 30 | 7 | ||||

| July 13 | 14 | 16 | 9 | ||||

| September 18 to October 1, 2024 | September 5 to September 25 | 3.62 | September 25 | 34 | 43 | 8 | |

| November 4, 2024 | November 5 | 29.6 | November 3 | 37 | 44 | 6 | 1 |

| November 4 | 16 | 20 | 6 | ||||

| April 1 to April 2, 2025 | April 2 | 12,708 | April 1 | 37 | 76 | 15 | 4 |

| April 2 | 31 | 59 | 23 | 8 |

(Source: Compilation by authors based on reporting from Xinhua and press releases from ROC MND, PRC Maritime Safety Administration, and Japan’s Ministry of Defense Joint Staff)

Military Implications

Two military implications emerge from the Strait Thunder-2025A drill. First, its scale suggests that future exercises may be even larger and include more maneuver objectives than previous ones. Second, the focus of the drill indicates that the PRC is likely to pursue tactics that involve creating concentric layers of encirclement around an opponent’s ships or islands.

Figure 3: Comparison of the Drill With Previous Similar Drills

(Source: Compilation by authors based on reporting from Xinhua and press releases from ROC MND, PRC Maritime Safety Administration, and Japan’s Ministry of Defense Joint Staff)

The first implication is inferred from the size of April’s drill, which was larger than previous drills but comparable to past exercises. As drills tend to be smaller in scope and complexity than exercises, this suggests future exercises could take place on a larger scale. The PLA has shifted in recent years from holding drills to conducting exercises and returning to drills. This may indicate that the PLA’s operations toward Taiwan have been validated, leading to simplified drills and preparations for future scenarios. In August 2022, the PRC referred to the actions it took in response to the visit of then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan as a “joint training drill” (Xinhua, August 4, 2022). This was conducted as part of military training and verification around Taiwan and intended to enhance the PLA’s capabilities in certain areas (Xinhua, August 6, 2022). This drill was followed by three “exercises” in 2023 and 2024, which were conducted based on the drills performed in 2022 and labeled “Joint Sword,” followed by a year and alphabetic designation. Subsequent activities have all been described as drills, including large naval training drills around Taiwan and the First Island Chain in December 2024 and the latest “Strait Thunder-2025A” (China Brief, December 20, 2024). A “Strait Thunder-2025B” is likely to take place in the coming months, but this does not necessarily mean that the PRC will stop conducting military exercises this year. The first installment of this series of drills also marks the normalization of training objectives and signals a systematic approach to using “Strait Thunder” drills to train and validate new military maneuvers or tactics for Taiwan-related operations. This preparation lays the groundwork for future large-scale military exercises and, ultimately, a potential invasion of Taiwan.

Figure 4: Comparison of Joint Sword 2024B Exercise and Strait Thunder-2025A Drill

(Source: Compilation by authors based on reporting from Xinhua and press releases from ROC MND, PRC Maritime Safety Administration, and Japan’s Ministry of Defense Joint Staff)

Second, the PRC has implemented its dual-layer “Cabbage Strategy” (包心菜战略) around Taiwan. The conventional Cabbage Strategy refers to the PRC’s use of maritime militia, official ships, and naval vessels to create multiple layers of encirclement around an opponent’s ships or islands (China News, May 27, 2013; New York Times, October 27, 2013). However, the drills this time demonstrate a new model, which we describe as a dual-layer Cabbage Strategy. On April 1–2, maritime militia forces appeared to join the large number of naval and CCG vessels participating in the drill. These forces consisted of several Chinese fishing vessels, one of which had collided with a Taiwanese naval ship in the Taiwan Strait several days prior, on March 27. On the morning of April 2, the day of the Strait Thunder-2025A drill, that same ship set out again from a port in Fuzhou to return to the site of the incident. This suggests the vessel is part of the PRC’s maritime militia, which includes a large fleet of fishing vessels that have a history of organizing units in Fujian province and, in recent years, of establishing units with the potential to operate as maritime militia near coast guard stations around the island of Kinmen, close to Taiwan (The Diplomat, September 20, 2024, December 24, 2024). The movements of this fishing vessel, along with those of three similar vessels in the Philippine Sea, strongly suggest that they are part of the PRC’s maritime militia. The operation of these ships both near and at a distance from Taiwan indicates that the maritime militia’s tasks around Taiwan are likely similar to those of the navy and coast guard, which include harassing Taiwanese and foreign vessels. For opponents within the inner circle, the sequence from inside to outside is militias, coast guard, and navy. For opponents outside the circle, the sequence from outside to inside also includes militias, coast guards, and the navy. This is what is referred to as the dual Cabbage strategy. These activities also add to growing evidence that the role and visibility of the maritime militia in Taiwan-related issues is growing (China Brief, March 15).

Conclusion

The PLA’s large-scale “Strait Thunder-2025A” drill on April 1–2 was a routine event. This speaks to the extent to which the PLA has normalized aggressive military behavior around Taiwan in recent years and the growing military threat it poses. The serial designation “A” suggests that the PLA will likely conduct similar large-scale drills around Taiwan again this year. Future joint military exercises, when they occur, will likely be even larger in scale and more complex in their objectives than others to date, further ratcheting up military pressure on Taiwan and contributing to regional instability.

Notes

[1] 全军军事术语管理委员会,军事科学院 [All-Army Military Terminology Committee, AMS], 中国人民解放军 军语 [Chinese People’s Liberation Army Military Terms], 军事科学出版社出版 [Military Science Publishing House Publication], 2011. This volume is the PLA’s authoritative dictionary of military terms, released by the PLA Central Military Commission in 2011. This edition was still the most recent version as of December 2023 (PLA Daily, December 1, 2023). Pages 311–315 focus on drills and exercises.

[2] On April 2, the only no-sailing zone in the coastal area under the Eastern Theater Command was located in Zhejiang. Analyst Joseph Wen has confirmed that the live-fire footage released by Chinese authorities was indeed filmed in Zhejiang (X/@JosephWen___, April 2).