The Securitization of Social Media in China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 3

By:

The crackdown on “human flesh searches” and including cybersecurity within the jurisdiction of the recently created National Security Committee, are the most recent episodes in a series that outlines the Communist Party’s concern and intent regarding social media. Xi Jinping’s administration is concerned that social media represents an innovative mechanism for petitioning and collective action that has proven at times capable of achieving concrete results in lieu of a tightly regulated environment for civil society mobilization. The intent is a comprehensive campaign against social media in order to circumscribe its perceived threat to one-party rule.

In an April 13 article originally published in Red Flag Journal, Ren Xianliang, deputy director of the CCP Shaanxi Provincial Propaganda Department and vice-chairman of the All-China Journalists Association, revealed the official position on social media. Ren called for the government to “occupy new battlefields in public opinion.” He noted that since the advent of Sina Weibo and other microblogs as platforms for “online political questioning and supervision” the Party’s task of controlling public discourse and information had become more difficult. He pointed to online agitators that manipulated public opinion, fabricated rumors and attacked the image of the Party and government, calling on the Party and traditional media to combat these threats (Xinhua, April 13, 2013).

By the end of April the Party had begun internally circulating the Minutes of the 2013 National Conference of Propaganda Chiefs. The Minutes, better known as Document No. 9, outlined the now well-discussed seven subversive topics including constitutionalism, civil society, and press freedoms. What is less mentioned about Document No. 9, however, is the inclusion of countermeasures: the consolidation and spreading of the Party’s voice; education on socialism with Chinese characteristics; and the strengthening of Party control over media (China Change, May 16, 2013). At a later national gathering of propaganda chiefs in August, Xi Jinping, echoing Ren Xiangliang’s rhetoric, ushered in the securitization of social media, calling on the propaganda department to build “a strong army” and to “seize the ground of new media” (South China Morning Post, September 4, 2013). Already underway, the crackdown on social media intensified for the remainder of 2013.

Is Cyberspace a Lawless Place?

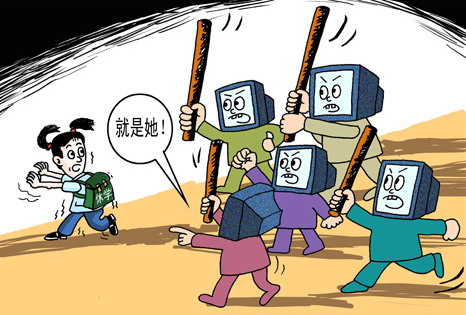

With each new regulation, Chinese authorities drew connections to stories about vigilantism and destructive panics caused by rumors propagated through social media, framing cyberspace as a source of insecurity and a social problem that demanded tighter censorship in the interests of public security.

Liu Zhengrong, a senior official with the State Internet Information Office, declared “human flesh searches” (renrou suosou), the independent online investigation into the personal details of a suspected wrongdoer, the final social media target of 2013 and called for the practice to be suppressed. On December 17, Liu cited the recent suicide of a girl in Guangdong after being wrongly accused of theft through a local “flesh search” as an example of the practice’s violent consequences, describing the “human flesh search” as a network of violence and emphasizing that cyberspace would no longer be lawless (Xinhua, December 18, 2013).

In late February 2010, in the middle of the night, tens of thousands of residents in multiple cities across Shanxi fled their homes in panic. The cause of this sudden movement was a rumor spread through chatrooms and text messages that a destructive earthquake was imminent. Similarly in 2011, rumors that an already accident prone chemical plant in Xiangshui, Jiangsu was about to explode caused a stampede as tens of thousands of residents fled to escape. Four people died in the rush. Recently, Qin Huohuo and Lierchaisi were arrested in August 2013 for, among other things, fabricating a story about a 30 million euro compensation of an Italian citizen who died in the 2011 Wenzhou train crash. Official media intensely cites cases such as these, evidently in an effort to legitimate tighter restrictions of online content to ensure “accurate” information and public security.

Who Has the Right to Investigate?

“Flesh searches” also function as a means of public engagement in a system without a functioning rule of law, in cases such as the famous “Li Gang” incident. In October 2010, a black Volkswagen sped along the streets of Baoding, near Hebei University. The car collided with two girls, killing one and severely injuring the other. The driver sped on and only stopped after being surrounded by a crowd, to emerge arrogantly and taunt them with the infamous, “My father is Li Gang!” Soon news of the incident spread online revealing the driver’s identity as Li Qiming, the son of the deputy director of the Baoding City Public Security Bureau. The father was dismissed and the son convicted after viral images of the family’s luxury properties well in excess of their salary were revealed through “flesh searches.”

Between January and October of 2013, the Bureau of Letters and Visits, the office responsible for accepting complaints at and above the county level, received more than six million petitions, averaging 20,000 per day (Global Times, November 28, 2013). Many petitioners, in addition to hand delivering these documents, or staging demonstrations and sit-ins, post their petitions on forums or Weibo. There they are often commented on and reposted. Official objectives stated elsewhere reveal a real concern for the degree of instability produced by unaddressed petitions but also point to an intention with the website to curb the unregulated dissemination of petitions and limit conversation between activists online. Petitions on Weibo can generate national attention and earn the support of accomplished rights lawyers.

Despite accounts of fabrications surrounding the event, the story of the deadly Wenzhou train crash itself was first reported by a Weibo user, after the Propaganda Department directed official media not to report on the incident. It is perhaps no coincidence that, four months after the crash, the General Administration of Press and Publications officially banned domestic journalists from reporting on information from Weibo.

It was this type of citizen journalism that Zhu Huaxin, secretary of the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Monitoring Center, attacked in an article following the announcement of the ‘rumors policy’ in 2012. His position in the article revealed a fear at the perceived loss of Party power to independent online actors (People’s Daily Online, October 11, 2013). Zhu, writing as far back as 2009, has been steady in his calls for the Propaganda Department to establish its cyber supremacy (China Youth Daily, July 24, 2009) in order to constrain sensitive online activity.

The policy on spreading rumors came less than a month after Xi Jinping effectively declared war on independent social media in August. The policy states that Weibo and other microblog users who are accused of posting “rumors” viewed more than 5,000 times or shared more than 500 times will be held criminally liable and face a maximum sentence of three years in prison. Supported by a judicial interpretation issued by the Supreme People’s Court and Procuratorate the policy expands existing crimes such as creating a disturbance or picking quarrels to apply to online activities (People’s Daily Online, September 9, 2013). Hundreds of bloggers and active Internet users were detained or arrested following policy implementation (Global Voices Advocacy, September 5, 2013). Yang Zhong, a 16 year old from Gansu, was one of the first arrested after posting challenges online to the official narrative of a local death in custody, but was released following considerable online defense (Global Times, September 24, 2013).

In the current campaign, we see Party efforts to not only censor independent accounts and persecute active Internet users, but to maneuver the Party to the forefront of narrative formation by providing “accurate” information. On the other hand, it also seeks to frame online crackdowns in paternalistic terms to legitimize censorship in the interests of public security. Such efforts to regain lost control online beyond crackdowns on content have included the rise of government websites promoted as the legitimate forums for previously diffuse online activities. The two most striking examples are the establishment of a corruption monitoring and reporting website by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, with the implicit intent of discouraging independent investigation and reporting on corruption, and an online complaints system set up by the Bureau of Letters and Visits, presumably to limit the flow of sensitive petitions via social media available to rights lawyers.

Lawyers also Tweet

Circumscribing online activity and shaping the content of digital information dissemination has not been confined to policies and announcements targeted at general civil society. Central Party efforts have also included attempts to specifically rein in online information dissemination by lawyers and directives to Chinese courts regarding the influence of online activity.

In 2012, the Supreme Court proposed that lawyers could be disbarred for blogging any trial information without court preapproval (Duihua, September 26, 2013). Many courts have started to liveblog proceedings, as a countermeasure to activist lawyers or independent observers. Promoted as an attempt to correct false reporting on high-profile cases such measures are also designed to secure Party domination of sensitive legal narratives. Constraining rights lawyers their ability to disseminate information online about their cases effectively serves to limit access to potential information for online activists.

Courts already have the ability to temporarily detain lawyers administratively through judicial detention, but the proposal to disbar them for up to a year for engaging in social media that threatens the interests of the court sent a clear signal. The proposed measure would likely have been exploited as a deterrent in the same way as the yearly lawyers license renewal has been used to harass more activist minded lawyers in recent years. As it is, the Supreme Court does not have the power to suspend licenses. This authority is vested with the Ministry of Justice but judicial interpretations and general announcements issued by the Supreme Court can carry considerable influence on local level courts.

In August, the Central Political and Legislative Commission (CPLC) issued a 15-point announcement aimed at addressing certain failures of the legal system. Provision 8 notes that courts and police are to disregard “public-opinion hype” and “petitioning by parties to the case” (Duihua, October 22, 2013). Following the CPLC announcement, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (Xinhua, September 6, 2013) and the Supreme Court (China Court Online, November 21, 2013) released implementation orders in September and November. These documents are concerned with public opinion, which depending on implementation could discourage online activism surrounding sensitive cases.

Such announcements are a direct response to the impact of public opinion, spread easily through social media, on influencing or forcing action in certain cases. When Li Tianyi, the son of well-known PLA singers Li Shuangjiang and Meng Ge, was first accused of leading the gang rape of a woman in a Beijing nightclub in 2013, many Chinese Internet users speculated that because of his status he would be afforded special treatment. After Li Tianyi was eventually sentenced to 10 years in prison, Zhejinag University law professor Lan Rongjie speculated that had the case not involved the scion of high ranking officials and generated such intense online attention, the 17 year old would likely have received a lesser sentence (Guardian, September 26, 2013). The court, Lan speculated, was reacting to protect its image, which had been challenged by online activism and thus handed out the maximum sentence. Online activism and public opinion has also had national achievements on court decisions and policy changes.

Conclusion

The series of announcements and legislation regarding online activity and social media in the latter half of 2013 illustrate efforts to circumscribe online civil society in much the same way as the government hopes to forestall threats to Party stability posed by traditional collective action. A National Security Committee was established in November during the Third Plenum (China Brief, November 12, 2013) and one of its stated targets unequivocally reveals this securitization of social media. In early January 2014 it was made public that among extremist forces and Western ideological challenges the newly formed security organization would prioritize cybersecurity, including online calls for collective action against the government (South China Morning Post, January 14). This focus conflates security with political stability, moving well beyond promoting “accuracy” for social stability. And with Xi Jinping at the helm of the nebulously powerful National Security Committee, we see the policy consolidation of the previously declared war on social media.