Tibet Railway Network Speeding Up to the Indian Border

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 21

By:

Introduction

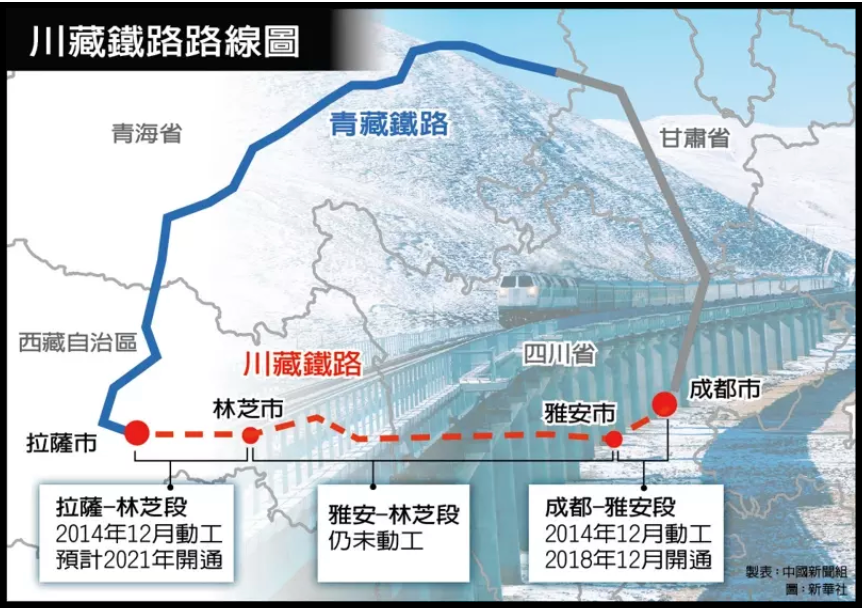

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is set to begin construction on a strategic stretch of railway between Ya’an city in the southern province of Sichuan and Nyingchi (Linzhi) city in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR, also commonly referred to as Tibet). The Ya’an-Nyingchi railway line (628 miles) comprises the middle sector of the Sichuan-Tibet railway line project (1,012 miles) which links the prefecture-level provincial capital cities of Chengdu and Lhasa. With the Chengdu-Ya’an section (87 miles) of the railway line complete and operational since December 2018, and the 270 miles of the Lhasa-Nyingchi stretch expected to be ready for use next year, the Ya’an-Nyingchi leg remains the only one left to build. This last phase is also anticipated to be the most difficult, due to complex geological conditions and a fragile ecological environment, Additionally, the Ya’an Nyingchi railway section will run through one of the world’s most active seismic regions (The Tribune, November 8). Construction is expected to take ten years, finishing in 2030 (Global Times, November 8).

When completed, the Chengdu-Lhasa railway will hook Tibet onto China’s massive rail network. It will be the second railway line to do so; a railway connecting Qinghai province’s Xining city and Lhasa began operations in 2006. Completion of the Chengdu-Lhasa railway project is important for the Chinese government. Speaking ahead of the project’s commencement, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping highlighted the railway’s importance, describing it as “a major step in safeguarding national unity and a significant move in promoting economic and social development of the western region” (Xinhua, November 8). Xi emphasized the key role that the project plays in the CCP’s plans for governance of the TAR and its strategy for securing national unity and stability in the border areas, and accordingly called for workers to speed up work on the Ya’an-Nyingchi line while carrying out construction in a “scientific, safe, and eco-friendly way” (Ibid).

The Sichuan-Tibet railway’s completion will no doubt bring economic benefits to the historically underdeveloped TAR, but it will also heighten already-complex regional tensions. Some Tibetans fear that more railway lines into Tibet will facilitate the plunder of natural resources by Beijing. The increased influx of Han Chinese migrants and tourists into Tibet is also expected to further impact local demography and culture, already under threat by China’s decades-long “Sinicization” policy (Beijing Review, August 31; VOA, September 3; see also China Brief, September 22). There is concern in India that the Chinese trains, which are poised to reach the disputed India-China border region soon, will further inflame the border conflict between the two nuclear powers that was rekindled earlier this year.

Economic Benefits of Overland Connectivity to China

The building of overland connectivity infrastructure into and within Tibet has been a central component of China’s strategy in the region that dates back to the 1950s. In the early decades, the Chinese government focused on road construction as a way of opening up the region. Prior to the annexation of Tibet, Chairman Mao Zedong is said (perhaps apocryphally) to have ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to “advance while building roads.” Improving overland connectivity into Tibet was necessary to transport the truckloads of PLA soldiers needed to put down local unrest and consolidate the PRC’s military and administrative control over Tibet. Its importance was seen as being equivalent to combat and undertaken with a similar aggression. [1] By 2018, China had built over 59,000 miles of roadway in Tibet (Xinhua, February 7, 2018). Chinese analysts today continue to highlight the role of infrastructure and road building for preserving China’s national unity (Indian Defence Review, August 6, 2016).

China’s railway building in Tibet began in 2001, and has gathered pace with the successful construction of the Qinghai-Tibet railway line in 2006. This line was subsequently extended to Xigaze (Shigatse) in 2014. In the decade and a half since its completion, the line has reaped economic benefits for both Tibet and the rest of China. China transports water and minerals from the resource-rich TAR to drought-stricken provinces in western and central China. At the same time, the railway has provided increased access to Chinese markets for Tibetan goods. Transport of goods into Tibet by train has become more cost effective, making essential commodities and consumer durables more affordable for many Tibetans. This has contributed to improving living standards overall. The increased ease of train travel has also boosted Tibet’s growing tourism industry. Between 2006 and 2014, Tibet’s GDP had an annual growth of more than 10 percent (China Daily, August 28, 2015; DNA, August 16, 2016; and Business Standard, December 28, 2016).

Chinese analysts have emphasized the similar benefits promised by the Chengdu-Lhasa line. The Sichuan-Tibet rail link would enable the transport of advanced equipment and technologies from other parts of China to Tibet and put the TAR on a “fast track” to catch up with the economic development of the rest of China—a crucial goal, as the Chinese leadership has prioritized poverty alleviation as a major goal (Xinhua, September 25; Global Times, October 31).[2] Indeed, the Sichuan-Tibet railway line is expected to create even more value than the existing Qinghai-Tibet railway. Qinghai’s economy is among the poorest of China’s 33 provinces; according to the National Bureau of Statistics, its accumulated wealth this year was the second lowest nationally, ahead of only Tibet (National Bureau of Statistics, undated). The new railway will connect Tibet to the central and eastern parts of China, including highly developed and wealthy regions such as the Yangtze River Economic Zone and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (Global Times, October 11, 2018).

Beijing Eyes ‘Border Stability’

Border tensions between China and India were renewed this summer, when violence broke out along the LAC in eastern Ladakh (China Brief, July 15). India is concerned about the strategic motivations that underlay China’s construction and extension of railway lines along the border region, which is de facto marked by the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Chinese analysts have not been shy to point out that in the event of a war with India, the Chengdu-Lhasa railway line will help with the “delivery of strategic materials” right up to the disputed Sino-Indian border (Global Times, October 31).

Although the summer’s violence has died down, repeated rounds of negotiations have so far failed to yield an acceptable compromise and forces on both sides appear to be digging in for a long winter (The Print (India), September 20; SCMP, October 12). In addition to building up troop numbers along the border, satellite imagery also appears to show continued construction activity by Chinese forces shoring up their position along the LAC (NDTV, November 30; India Today, December 1).

India and China both claim large chunks of territory under the other’s control: in the western sector of the LAC, India claims around 14,670 square miles territory in the province of Aksai Chin and another 1,930 square miles in the Shaksgam Valley of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (also referred to as the Trans-Karakoram Tract), provisionally put under Chinese control in 1963. China claims a total of around 35,000 square miles of territory along the eastern sector of the LAC, which it considers to be part of the historic territory of Tibet. This territory is currently administered under the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

The Chengdu-Lhasa railway line runs dangerously close to this last contested region. Nyingchi—the terminus city of the railway’s last section to be completed—is located less than 10 miles from the LAC, just north of India’s Tuting sector in the Upper Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh. In the event of a border conflict between China and India in the eastern LAC, the new railway line would allow the PLA to swiftly mobilize trainloads of soldiers directly to the frontline.

Originally a garrison town in southeastern Tibet, Nyingchi is currently home to the PLA’s 52nd and 53rd Mountain Infantry Brigades as well as one of Tibet’s four dual-use airports. Beijing has dedicated substantial resources to building up the connective infrastructure that links the border city with the rest of China. The completion of a 254 mile highway between Lhasa and Nyingchi in 2017 cut travel time between the two cities from eight to five hours (Xinhua, October 1, 2017). Once trains begin arriving at Nyingchi from Lhasa next year, the trip will only take three hours. From the other direction, the trip from Chengdu to Nyingchi will be shortened by roughly two thirds (Business Standard, November 2).

Alongside its construction of connectivity linkages, China has also been beefing up its military infrastructure at Nyingchi. Satellite images reveal that the airport and helipads have been upgraded over the past few years. Barracks and sheds to accommodate large numbers of troops, armored vehicles and other equipment are also being built (India Today, July 1).

In addition to the planned route to Nyingchi, China is also extending its railroads to other border towns in Tibet. In 2018, China and Nepal signed agreements to cooperate on plans to extend the existing Lhasa-Xigaze line to Gyirong, a trading town near the border with Nepal, and to connect this line to Nepal’s capital city of Kathmandu (China Daily, June 22, 2018). There are also plans to extend the Lhasa-Xigaze railway line southwards to Yadong, although these appear to have been delayed (China Daily, June 29, 2006). A trading town near the strategic Nathu La mountain pass that runs between Tibet and India in the eastern sector of the LAC, Yadong is also close to western Bhutan, where China has territorial claims in the Doklam plateau. [3]

Economy or Territory?

Chinese officials have often claimed that the railway lines to the Tibet-Indian border are aimed at developing the economies of remote areas, and the central government has encouraged more prosperous provinces to invest in places like Nyingchi. Guangdong province, for instance, is investing in 51 projects worth $78 million in Nyingchi this year. China has repeatedly touted the economic benefits of such infrastructure building, which is expected to boost local tourism, open up employment opportunities for locals and increase income for farmers and herders (China Daily, June 11). Chinese state media has also frequently portrayed the Lhasa-Xigaze railway link as a means for accessing the Nepalese and Indian markets, overlooking its dual use military purposes and omitting discussions of the negative implications for India-China border security (Global Times, May 24, 2016).

Although Indian analysts recognize that the Chinese railways could boost regional trade, they are skeptical that such trade will actually benefit India (China Brief, September 13, 2016). Additionally, the recent escalation of tensions along the LAC—particularly along its western sector since May this year—has made India more sensitive to the role that railroads would play in the PLA’s mobilization of troops to the border. Indian observers have not overlooked the fact that many of the towns along the LAC where Chinese trains are planned to arrive have been the site of major crises and face-offs between the PLA and Indian security forces in the past.

Yadong, for instance, is located near Doklam, where Indian and Chinese forces were locked in a 73-day standoff in 2017. Shortly after the Doklam crisis, Chinese soldiers trespassed onto the Indian side of the LAC in Arunachal Pradesh. Nyingchi is not far from where the point of intrusion occurred. Indian media reports characterized this as a Chinese attempt to open a second front against India (Times of India, January 10, 2018). Future Chinese intrusions at these points could be orders of magnitude larger, with the PLA shipping troops to the frontlines by train.

Conclusion

This year has seen renewed Chinese efforts to assert control across a variety of sovereignty issues ranging from the crackdown on political autonomy in Hong Kong to overt clashes with Japan, Malaysia and Vietnam over hydrocarbon exploration and fishing rights in the South China Sea. Some western observers fear that as China is strengthened by a strong economy (contrasted with ongoing global turbulence due to the COVID-19 pandemic), it may be taking advantage of opportunities to assert itself by building infrastructure and “changing facts on the ground,” cementing its position in disputes over contested territory while its opponents are distracted.[3] In 1962, the building of roads into Tibet emboldened China to wage a border war against India. There is concern in India now that with its railway network into and within Tibet expanding, and railway lines poised to soon reach the LAC, Beijing may feel emboldened to flex its military muscles more resolutely to unilaterally alter its border with India.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bangalore, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asia Times and Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor.

Notes

[1] John W Garver, Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 80–88.

[2] Since the country’s founding, China’s economic development has been weighted towards its richer east coast. After nine counties in China’s southwestern Guizhou province were declared poverty free, Chinese officials claimed on November 23 that they had successfully eliminated “absolute poverty” nationwide and achieved one pillar of the CCP’s stated aim to build a “moderately prosperous society” ahead of the party’s hundredth birthday in 2021. See: James Areddy, “China Says It Has Met Its Deadline of Eliminating Poverty,” Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-says-it-has-met-its-deadline-of-eliminating-poverty-11606164540.

[3] See: Steven Lee Myers, “Beijing Takes Its South China Sea Strategy to the Himalayas,” New York Times, November 27, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/27/world/asia/china-bhutan-india-border.html.