Ukraine Struggles to Stem Cross-Border Supplies to Russia’s Proxy Forces

By:

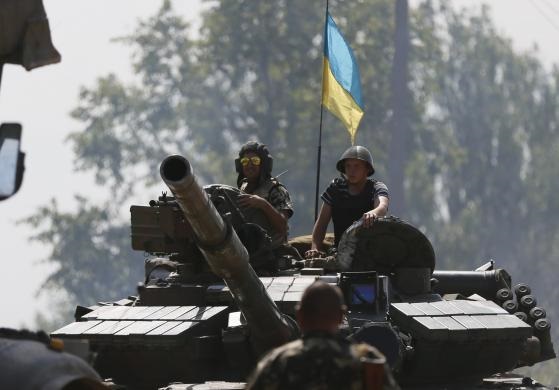

Russia reinforces and resupplies the secessionist troops in Ukraine’s east across certain sections of the border. The cross-border flow continued unabated during Ukraine’s two unilateral ceasefires (June 20–30), enabling pro-Russia forces to stage attacks throughout the conflict zone. This required Kyiv to seize the initiative and liberate four districts by July 6, in spite of diplomatic pressures to continue the ceasefire (see accompanying article). These events demonstrate that ceasefires are self-defeating for Kyiv as long as Russian arms and fighters can cross that border. Conversely, to sustain the secessionists, Moscow needs to prevent Ukraine from establishing full control on the Ukrainian side of that border.

Pro-Russia forces have repeatedly attacked Ukrainian border-crossing stations from within Ukrainian territory, disabling or destroying some of them. Between April and June, Ukrainian border guards lost control of long sections of the border. Ukrainian forces are incrementally regaining control in uneven degrees, sector by sector. They retook the Dovzhansk border crossing station on July 1 and repelled secessionist attacks on it from the Ukrainian side of the border during the ensuing week (Ukrinform, July 7).

According to the US ambassador in Kyiv, Geoffrey Pyatt, “the Russian frontier has been a sieve for tanks and missile systems and MANPADs, and money and mercenaries,” entering Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk provinces (Kyiv Post, July 1). According to US General Philip Breedlove, commander-in-chief of NATO forces in Europe, Russia has recently transferred additional tanks, armored personnel carriers, anti-aircraft guns, and other hardware to pro-Russia irregular forces in Ukraine’s east; while Russia’s own regular forces along the border facilitate that movement of military equipment across the border (VOA, June 29, cited by Ukrinform, June 30, www.ukrinform.ua).

Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) chairman, Valentyn Nalyvaychenko, confirms that Russia has not closed its side of the border, and instead continues supplying secessionist forces in Ukraine’s territory. Consequently, any “ceasefire would only become realistic when Ukraine regains control of its own side of the border” (Interfax-Ukraine, Unian, July 4). Kyiv is drawing its conclusions from the unilateral ceasefire it had accepted at the insistence of certain West European governments (to which Kyiv is more sensitive than Moscow and the secessionist leaders would be).

In a similar vein, spokesman of the Ukrainian National Security and Defense Council (NSDC), Andriy Lysenko, announced that any questions about halting military actions “would be considered only after the [insurgents] have fully complied with the peace plan, including: their withdrawal from cities and villages, disarmament and return of all sectors of Ukraine’s state border to Ukrainian control, with the involvement of OSCE monitors to supervise the situation [on the border]” (Ukrinform, July 7). This statement also confirms that the Poroshenko peace plan (briefly derailed on July 2 in Berlin) is back (see EDM, June 26, July 3).

Beyond Ukraine’s vital national security requirements, a poorly controlled border also jeopardizes Ukraine’s negotiations with the European Union about travel visa facilitation and liberalization. This is a national goal that also reflects on the pro-Europe government’s domestic political standing. The EU, however, will hardly move to relax visa regulations, unless Ukraine reliably controls its side of the Ukrainian–Russian border. On June 27, Ukraine completed the signing of its Association Agreement with the EU. It should be assumed that EU governments would unconditionally encourage Ukraine to control its side of the border with Russia.

Russian and German diplomacy (with French support) have linked the question of restoring Ukrainian control of the border with the question of armistice negotiations between Kyiv and the pro-Russia forces. Proposals developed jointly by Moscow and Berlin would allow Ukraine to regain some control of a few border sectors, contingent on Kyiv accepting a negotiated armistice with the pro-Russia forces. The control arrangements would only be introduced with an armistice and would lapse with the armistice. This conditionality is meant to tie Ukraine’s hands. It is set in the quadripartite declaration signed on July 2 in Berlin, as well as in proposals discussed at the highest levels between Moscow, Berlin and Kyiv during late June and early July (see EDM, July 3, and accompanying article).

Berlin is aware that Kyiv could only consider Russo–German proposals for an armistice if accompanied by guarantees that the border would be reliably controlled. Moscow must realize this also, but Moscow wants a border control system with loopholes, allowing it to support its proxies in Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk provinces during any ceasefire and negotiation process. Berlin has recently tried hard to fix this problem, so as to “de-escalate” the Russia-Ukraine conflict and go on to “normalize” German–Russian (and EU-Russia) relations.

Thus, devising arrangements for control of the Ukrainian–Russian border has become a matter for top-level negotiations: principally between Germany, Russia and Ukraine, with occasional inputs from France (supporting the Russo–German initiative) and the United States (supportive of Ukraine). Chancellor Angela Merkel as well as Presidents Vladimir Putin of Russia, Petro Poroshenko of Ukraine and Francois Hollande of France have held a series of telephone conferences in variable formats to negotiate control arrangements for the Russia–Ukraine border. They have treated the issue of border control as one of the prerequisites to a ceasefire and negotiations between Kyiv and the Donetsk–Luhansk secessionists.

Establishing Ukrainian control of the border must be treated as a top-priority goal in its own right, not contingent on Ukraine’s acceptance of armistice terms favoring the Russian side. It is Moscow who should be pressured to discontinue the flow of fighters and weapons across the border (“de-escalation”). Credible threats of Western sanctions can persuade Moscow to desist.