Ukraine’s Gas Storage System: A Unique Asset in Europe

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 130

By:

Addressing Gazprom’s annual general meeting of shareholders, CEO Alexei Miller warned that Gazprom would “never again, under any circumstances” use Ukraine’s gas storage system in the process of delivering Russian gas to Europe via Ukraine (Kommersant-Ukraina, July 4; Nezavisimaya Gazeta, July 10; see EDM, July 15). This public threat is unprecedented. Whether to be taken at face value or as a bluff, it signifies another attempt to intimidate Ukraine into giving up its gas transportation system to a bilateral “consortium” with Gazprom.

The storage system is a vital asset to Ukraine and also a unique one, since Gazprom has nothing remotely comparable with it in Europe. As long as this remains the case, Russia can hardly “boycott” Ukraine’s gas storage system. Moscow can, however, gradually reduce its use of Ukrainian storage sites, in step with the reduction of Russian gas transit volumes via Ukraine to Europe.

Such threats imply that Russia would sharply curtail its use of Ukraine’s gas transit system for exports to Europe, building bypass pipelines instead, and possibly bankrupting Ukraine’s transit system, unless Kyiv allows Gazprom to take over the pipelines and storage sites. Meanwhile, Gazprom’s bypass projects are short of storage capacities or lack them altogether. Gazprom had considered building or taking over storage capacities in some European Union countries next to Ukraine, but it failed to do so in recent years.

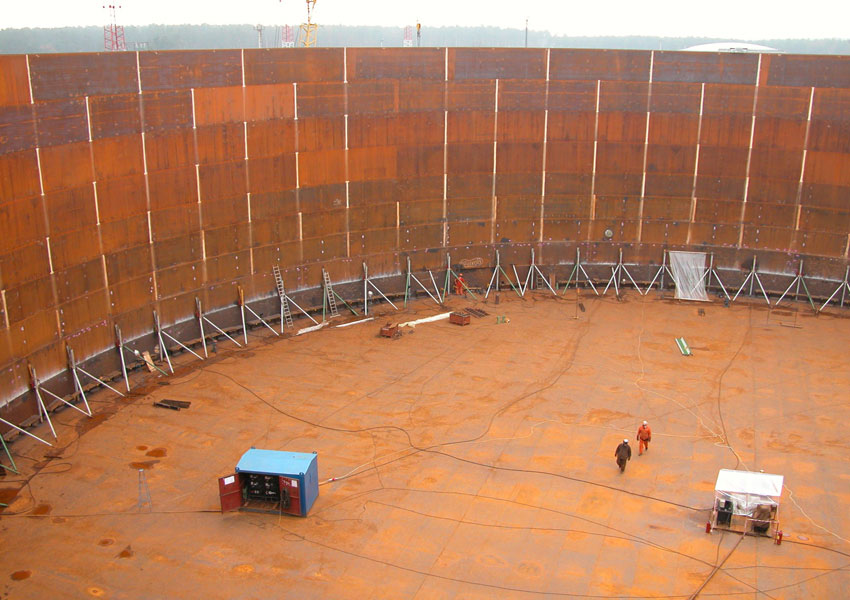

Ukraine’s gas storage capacities exceed by far the capacities available in any European country outside Russia. The Ukrainian system has a total storage capacity of 32 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 13 underground storage sites, 12 of these operated by UkrTransHaz and one operated by ChornomorNaftohaz (both storage operators being fully-owned subsidiaries of the state-owned holding Naftohaz Ukrainy). Injected with gas during the low-consumption season, this storage system is capable of delivering between 250 million cubic meters and 300 million cubic meters per day during the peak-consumption months of the year (www.naftogaz.com, www.utg.ua, accessed July 14).

The Ukrainian storage system is mainly designed to service Russian Gazprom’s exports to Europe. A portion of the stored gas is set aside every year to balance Ukraine’s internal consumption of gas.

Ukraine’s gas storage capacities are concentrated overwhelmingly in the vicinity (but not immediate proximity—see below) of Ukraine’s borders with Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. In that part of Ukraine, five storage sites account for almost 80 percent of Ukraine’s total gas storage capacity. They also account for nearly 80 percent of the system’s total daily gas withdrawal capacity during high consumption.

Gazprom exports the lion’s share of its gas from Ukrainian storage via Slovakia’s “gas highway” (four pipeline strings) to the Czech Republic, the Baumgarten continental hub near Vienna, thence northward to Germany and southward to Italy. Other pipelines deliver Gazprom’s gas to Poland and Hungary from the Ukrainian storage sites. However, no storage site services the transit pipeline that sends Russian gas to Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey from Ukraine.

Gazprom is the main user of Ukraine’s storage system, supporting Gazprom’s exports to Europe. Meanwhile, the transit of Russian gas to Europe via Ukraine has declined from a peak of 137 bcm in 2004, to 117 bcm in 2008 (the last pre-crisis year), to 104 bcm in 2011 and to 84 bcm in 2012. The transit amounted to 38 bcm in the first six months of 2013 (UNIAN, July 11). This downward trend is correspondingly freeing up storage capacity in Ukraine.

Thus, substantial storage capacities are becoming available in Ukraine’s west for possible use by interested European importers. The Ukrainian government therefore considers offering storage services directly to European companies. Using parts of Ukraine’s vast existing capacities would obviate big capital investments to build new underground storage sites. It could fit in with EU proposals to mandate storage of natural gas, analogously with the oil stockpiles, as a basic supply security measure.

According to Energy Minister Eduard Stavytsky, Ukraine could rent or lease capacities for interested European companies to store gas volumes, irrespective of those volumes’ provenance (whether delivered by Gazprom or sourced from other suppliers). The service could be used by companies based just across Ukraine’s western borders or farther afield. According to Prime Minister Mykola Azarov at the latest EU-Ukraine Cooperation Council session, the storage system in Ukraine’s west can potentially serve as a gas trading hub. This would involve a distribution center and spot market pricing. The energy ministry is drafting proposals for approval by the Cabinet of Ministers to abolish export duties on natural gas, so as to facilitate its re-export in any direction (Interfax-Ukraine, Ukrinform, June 26, July 3; Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, July 8).

Legal and technical impediments do exist. Gas from Ukraine’s western storage sites must travel a certain distance to the western borders (see above) through the transit pipelines. Gazprom, however, insists on booking those pipeline capacities in advance and fully or almost fully. This issue among others would involve complicated negotiations. Ultimately, however, the credibility of Ukraine’s proposal will hinge on reforming Ukraine’s gas sector. Next year’s presidential election seems likely to delay that reform yet again.

Gazprom’s bypass pipelines (completed or planned), with all their gigantic transmission capacities, practically lack storage capacities. Blue Stream and Nord Stream have none, while plans for South Stream envisage using only one, relatively minor storage site, already existing in Serbia. According to some Moscow experts close to the government, such as National Energy Security Foundation president Konstantin Simonov, the Blue Stream pipeline has, from time to time, been used as a substitute storage site, and portions of Nord Stream’s capacity can also be used as needed for storing gas (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, July 1).

Such suggestions confirm indirectly Moscow’s intentions to use newly built pipelines to Europe at less than their designed transmission capacity (see EDM, April 22). For the time being at least, Gazprom is short on storage capacity in Europe. The Ukrainian storage system provides the country with some counter-leverage. But this unique asset’s value could dissipate if Ukraine continues delaying the reform of its natural gas sector.