Will Georgia Continue to Seek to Influence Eurasian Countries?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 212

By:

Most of the non-Russian countries in the post-Soviet space have pursued foreign policies directed at defending their interests “in the framework of a limited geographic region,” two Russian analysts say. But under President Mikhail Saakashvili, Georgia has been an exception, regularly seeking to promote itself as a model of development across the entire area. The question now is whether the new Georgian government will do the same or whether it will scale back these efforts.

In an article posted on the “Novoye Vostochnoye Obozreniye” portal last week, Nikita Mendkovich, a specialist at the Creative Diplomacy Center, and Dmitry Aleksandrov, a scholar at the Russian Institute of Strategic Research, argue that however things turn out to be, an analysis of what Tbilisi has been trying to do is important because it helps to clarify “the mechanisms of information and political competition in the post-Soviet space that can be used both by Russia and by its competitors” (www.ru.journal-neo.com/node/119704).

The current article builds on one that Mendkovich published earlier this year on Georgia’s information strategy. There he noted that Tbilisi under Saakashvili had used “the internal resources of opponent countries” rather than seeking to “create or purchase an adequate information machine,” and that Georgia was able to do so because of the continuing influence of what he called “the neo-liberal intellectual community” in those other post-Soviet countries. Despite that resource, Mendkovich concluded, Georgia had not succeeded in winning over broader public opinion to its side in most post-Soviet states. “The key directions of Georgian media and ideological expansion are now Central Russia, the North Caucasus and other republics of the South Caucasus. In the latter two, Tbilisi has had some limited success, Mendkovich said, but much less than it had hoped (https://www.ru.journal-neo.com/node/117461).

In their new article, Mendkovich and Aleksandrov use Georgia’s efforts over the last five years in Kyrgyzstan as the basis for their broader conclusions. For much of the post-Soviet period, Kyrgyzstan was very much on “the periphery of the foreign policy attentions of Tbilisi.” Georgia was represented there by an embassy based in Kazakhstan. But with the presidency of Roza Otunbayeva, who earlier had worked closely with then-Soviet Foreign Minister and Georgian leader Eduard Shevardnadze, things began to change. Her ties to Georgia, the two writers say, grew when she served as a deputy special representative of the United Nations Secretary General for the Resolution of the Georgian-Abkhaz dispute in 2002–2003. At that time, the Kyrgyz diplomat developed close relations with Mikhail Saakashvili.

Further cementing the relationship was Otunbayev’s decision as head of Kyrgyzstan’s provisional government to hire the Georgian public relations firm, Policy and Management Consulting Group, headed by Aleksi Aleksishvili, who was also a member of the government of Georgia for three years after the Rose Revolution. Those ties at the highest levels in Bishkek and Tbilisi were reinforced by contacts at lower levels and by expanding international trade between the two countries.

The bilateral relationship, actively promoted by Saakashvili, led in 2011 to the establishment of an inter-governmental commission on trade and economics, a body which Georgian participants used to popularize Black Sea resorts and the possibility of a direct air route between Georgia and Kyrgyzstan, Mendkovich and Aleksandrov say. But they add that “the potential for economic cooperation of the two republics is limited by objective factors” and that one should not expect any significant rise in trade turnover regardless of who is in power.

Georgia also sought to promote itself in Kyrgyzstan by providing humanitarian assistance to that country’s south after the June 2010 violence there, the two say. But the impact of that aid was counter-productive because much of the medicine that Tbilisi sent turned out to be old and past its use date, a fact that some in Bishkek played up against Georgia.

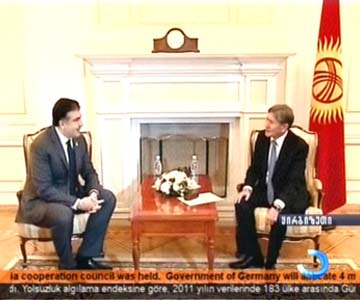

According to the two Russian authors, after Otunbayeva left the presidency in 2011, she and her colleagues “did everything possible to preserve the influence of Georgia in the country,” including inviting Saakashvili to come to the inauguration ceremony for her successor. Moreover, with her cooperation, Georgian lobbyists in Kyrgyzstan pushed for the creation of a free trade zone, the elimination of double taxation and also agreements on standards and measures. These accords still are likely to be signed “even though they have been much criticized by Kyrgyz parliamentarians,” the Russian authors suggest.

Georgia now has an honorary consul in Bishkek, but “the main form of realizing Georgian influence in Kyrgyzstan remains the intensive exchange of delegations of officials and political and social activists, during the course of which, Mendkovich and Aleksandrov say, “the representatives of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan have been subjected to an ideological working over.” All this has promoted the appearance of “a certain fashion for Georgia in the political elite of Kyrgyzstan,” with many authors suggesting, convincingly in the view of the two authors of the current article, that this is connected with “a vacuum of ideas and strategic plans in the leadership of the republic [Kyrgyzstan], which thanks to the efforts of Tbilisi has been partially filled by ‘the Georgian model of reform.’”

A major reason that Georgia achieved what it has in this regard, Mendkovich and Aleksandrov suggest, is that “in addition to the advancement of its own goals, it is a promoter of American interests in the region.” Indeed, they say, it often happens that pro-US officials in Kyrgyzstan present their views as a form of support for “a Georgian vector” and of Georgia’s successes as a reform-minded country.

The results of the parliamentary elections in Georgia so far are having “an extremely negative” impact on Tbilisi’s influence in Kyrgyzstan and elsewhere in Central Asia, the two say, because these events “have led to the discrediting of the model that had been proclaimed earlier. “But,” they add, “there is reason to believe that the new government [in Tbilisi] will seek to use the ties that have been built up with the politicians and experts of Kyrgyzstan for the preservation of its influence in the region,” all the more so, they argue, because “the American leadership is not inclined to break quickly with [any of] its geopolitical projects.”