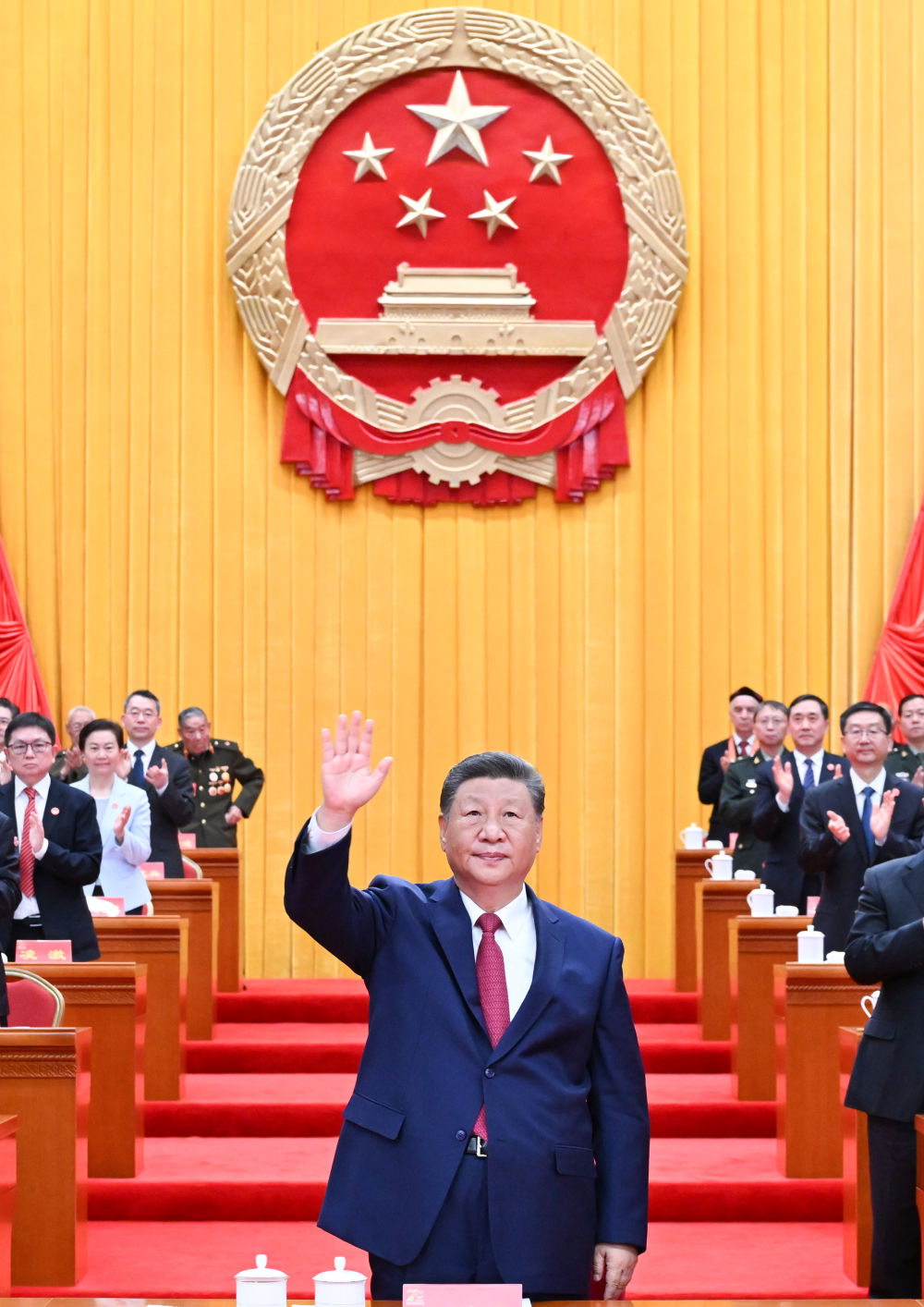

Xi Jinping Challenged Following Spate of Violent Attacks

Xi Jinping Challenged Following Spate of Violent Attacks

Executive Summary:

- Xi Jinping faces mounting challenges to his legitimacy from multiple directions, with economic troubles, mass killings, and corruption in the military eroding his grip on power.

- A spate of unrelated violent incidents and rising social protests across the People’s Republic of China (PRC) indicate severe social malaise stemming from the country’s decelerating economy.

- Beijing’s initial response has been tepid, focusing on repression through increased stability maintenance measures and enhanced surveillance of vulnerable groups.

- The suspension of Central Military Commission member and Xi Jinping protégé Miao Hua (苗华), as well as Xi’s absence from recent high-level military meetings, are additional unforced errors from Xi.

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda repeatedly claims that “Chinese people are the happiest in the world (中国人幸福感全球最高)” and that they live in a country that is “among the safest in the world (世界上最安全 … 国家之一)” (CCTV, March 20, 2023; MFA, November 13). These claims have been torn asunder by a spate of violent incidents that have been described as quasi-terrorist attacks (Sohu, November 13). On November 11, a man surnamed Fan (樊) knocked down and killed at least 53 men and women in an athletic arena in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province. Police believe that the incident was triggered by Fan’s dissatisfaction with a judge’s ruling on the division of assets in his divorce proceedings (Initium Media, November 18). Since then, copycat incidents involving students and laid-off workers launching apparently indiscriminate attacks stabbing and wounding passers-by have taken place in Guangzhou, Wuxi in Jiangsu Province, Changde in Hunan Province, and Baoding in Hebei Province. October also saw a mass stabbing incident in a Shanghai supermarket (Youtube/Hong Kong 01, November 17; BBC, November 19; Lianhe Zaobao, November 21).

Social protests in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) increased 27 percent in the third quarter of 2024 over the same period in 2023, according to the China Dissent Monitor, a project run by US think tank Freedom House. Most of these violent cases were due to economic disputes between factories and workers, such as laborers being laid off or failing to be paid the wages promised by bosses in both written and unwritten contracts. Some employers, however, have fled the country due to the deteriorating business environment (China Brief, October 11; Freedom House, November 21; Bloomberg, November 21).

Unrest Met by Repression

The response to what Beijing calls “extreme cases (恶性事件)” from the administration of supreme leader Xi Jinping was initially tepid. The government has not admitted that the acts of random violence might reflect ordinary people’s frustration at failures to improve employment opportunities among the young or buttress the country’s fragile and insufficient social welfare provision. Reforms to the country’s labyrinthine justice system have also done little to improve people’s sense of security. A stimulus program unveiled in September that was expected to amount to 10 trillion renminbi ($1.4tn) has been pared down, and now constitutes a mere RMB 6 trillion ($830 billion) in credit spread across three years to overleveraged local governments (CCTV, November 8). This stimulus will do little do assist these governments, which have accumulated debts of ten times this amount (Radio Free Asia, November 18; CGTN, November 18). Meanwhile, other measures signaled by the government, such as an injection of more social-welfare funds and subsidies for citizens buying big-ticket items such as fridges, televisions, and other household appliances, have been underwhelming. Rural residents are only eligible for RMB 214 ($30) a month for old-age benefits. Workers at state-owned enterprises in cities receive over RMB 3,160 ($440) (Xinhua, November 5).

Xi’s response to the recent social upheaval has been to fall back on traditional CCP methods. Instead of ensuring a more equitable distribution of the economic pie or courting foreign multinationals to invest in the PRC, he has doubled down on strengthening control of the populace through boosting the “stability maintenance (维稳)” apparatus. Xi has mandated more surveillance and control over “eight types of losers (八失人员)” in society. These include citizens who have lost money on investments or are unemployed; people who are dissatisfied with their way of life, are emotionally frustrated, are mentally unstable, have psychological abnormalities, or whose relationships with spouses and friends are turbulent; and unsupervised juveniles. Xi has also urged national security forces to pay more attention to people with “three lows and three insufficiencies (三低三少).” The former includes people with low incomes, low social status and low social prestige; the latter covers those who have few relationships or social networks, those with few opportunities for social and geographical mobility, and those who have no access to counselling (New York Times Chinese Edition, November 14; Voice of America, November 19). These are groups of people who historically the state has failed and who have slipped through the social safety net.

Several tools have been deployed to achieve this social engineering. One response has been for cities to ban large gatherings of people. Similar measures were used by police during Halloween this year, as authorities were apparently worried that people would take the opportunity to dress up in costumes mocking senior officials (Initium Media, October 28). At the same time, authorities have promoted the so-called “Fengqiao Experience (枫桥经验)”—a prominent propaganda initiative revived by Xi in 2013. Originally, this referred to a social experiment enacted by Mao Zedong in the township of Fengqiao, Zhejiang Province. Mao asked families in the area to keep an eye on each other and to report to the police people suspected of acting against the Party (China Media Project, April 16, 2021; CCP Members Net, November 24, 2023). This method of social control harks back to the “shared responsibility (连坐)” system first advocated by Warring States-era (476–221 BCE) thinkers commonly referred to as adherents of the Legalist School. Under this system, in place for much of Chinese history, people could be found guilty of crimes by association with the perpetrator (Beijing Politics and Law Net, December 18, 2020). Although technically unconstitutional in the PRC, the practice of guilt by association by authorities persists today in some localities in specific instances (China Court, January 11; Eastmoney, January 12).

Unrest Indicates Increased Pressure on Xi

Xi’s authority in a number of policy arenas has been challenged. Even if he secures an unprecedented fourth five-year term of office in 2027, as seems likely, he will face mounting challenges. One group that appears particularly hard hit are young people in the 16–25 age bracket. Not only has unemployment remained acute for this demographic since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the most recent bouts of violence were preceded by a series of mass suicides by young people that shook communities and made waves across social media earlier this year (ChinaAid, May 30; China Worker Forum, April 3).

Xi also seems to have lost some of his power within the Central Military Commission (CMC). He was absent for two meetings in recent months on important functions in military doctrine and strategy, which were instead led by CMC Vice-Chair Zhang Youxia (张又侠), who is the second-most powerful member of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (PRC MND, September 13; October 22).

The suspension of CMC member and Director of the CMC’s Political Work Department Miao Hua (苗华) at the end of November for a disciplinary inspection compounds Xi’s problems (PRC MND, November 28). This is not the first time he has been forced to remove former protégés as part of a thorough purge of the top brass and will not have been well received by his many internal detractors. The clearest signal of Xi’s anxiety about the loyalty of his top generals is his decision earlier this year to install his wife, Lieutenant-General Peng Liyuan (彭丽媛), to oversee discipline and promotion assessments within the upper echelons of the PLA (China Brief, May 24).

Conclusion

It is often unwise for an embattled leader to embark on a lengthy overseas trip. Xi’s recent travels to Latin America for a state visit and to attend the APEC and G20 summits could suggest that he deems things to be relatively under control on the home front. However, back home people have noted the continued lavishing of billions on overseas infrastructure projects while welfare benefits at home remain meager (Beijing Spring, November 2024).

The proliferation of violent attacks in disparate parts of the country indicate that, for some in the PRC, a crisis point has been reached. Economic malaise has begun to manifest as pervasive social malaise, to which the Party appears ill-equipped to respond. Meanwhile, ongoing problems at the top of the Party’s military apparatus mean that Xi is receiving signals from multiple directions that his legitimacy is eroding (Radio Free Asia, November 21; Voice of America, September 9). For now, however, Xi appears to have made the bet that the PRC’s economic fundamentals will steadily improve and, with that, social stability will return to a more manageable level.