Xi Shifts Blame as Chinese Economy Continues to Falter

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 13

By:

Introduction

In December of last year, China’s central government lifted its stringent “zero-COVID” restrictions, signaling to the public it shifted its principal policy objective from pandemic prevention measures to jump-starting China’s flagging economy (Japan Times, April 16). In the first quarter of 2023, the country seemed to be recovering as growth accelerated to 4.5 percent—compared to only 2.9 percent in the final quarter of last year (Xinhua, April 13).

Looking beyond GDP growth figures, however, China’s overall recovery appears to be far slower than previously anticipated. Consumer demand remains stifled and industrial activity has fallen. China, the world’s largest manufacturing economy and leading exporter, has experienced its most significant decline in exports in the past three years (SCMP, June 20). Chinese stock indexes are losing value as shareholders move their money to safer investments. Meanwhile, investment in the property sector, a highly consequential industry, is significantly diminished as consumers are afraid of spending (SCMP, July 17). To add to the country’s economic woes, youth unemployment is steadily rising.

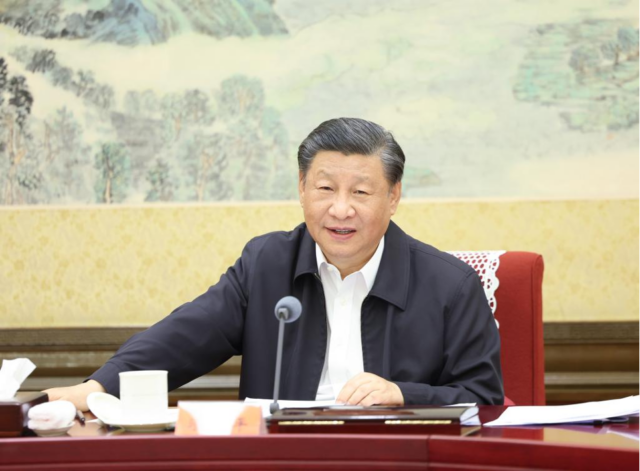

Given the central government’s official position that the zero-COVID policy was a resounding success, Chinese President Xi Jinping may feel compelled to identify alternative explanations for the country’s lackluster economic performance. Consequently, state officials will likely externalize accountability onto other actors. This trend is already observable in official state discourse, as the central government points fingers at various demographics, ranging from private entrepreneurs to recent college graduates.

Assessing the Post-Pandemic Recovery

During the pandemic, consumption fell due to nationwide lockdowns coupled with a general economic downturn. “Revenge spending”—expected after the lifting of zero-COVID restrictions—has failed to materialize, with consumer demand missing its target for this year. Initially, some of China’s key industries appeared to show promising signs of recovery. The transportation, accommodation, and catering sectors saw revenues rising, with retail sales boasting an 18.4 percent gain in April (Global Times, 2023, June 15). Immediately after the May Day holiday, however, things began to slow down again as the central government only reported a 12.7 percent year-on-year gain (Global Times, 2023, June 15). To put this growth in perspective, it is important to note how poor sales were the previous year. In April 2022, retail sales were down 11.1 percent year-on-year while in May they were down 6.7 percent (Global Times, 2022, June 15). In context, much of this year’s growth only represents “catch-up” after three years of a debilitating economic downturn.

As Chinese state media reported, “officials… acknowledged some ‘constraint factors’ that are dragging domestic consumption” (Global Times, 2023, June 15). After enduring three years of economic uncertainty, Chinese consumers are increasingly hesitant to spend. Moreover, manufacturing activity is struggling to recover to pre-COVID levels. Overall, five key data points seem to indicate that the Chinese economy is struggling to find its footing: a decline in export quantity, a drop in factory gate prices, a fall in China’s manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), the devaluation of the yuan, and a strained property market.

The first factor indicative of China’s faltering economic recovery is a decline in demand for Chinese exports. Despite China’s best efforts to revitalize its manufacturing sector, a challenging external environment has hampered the PRC’s prospects for an economic rebound. Trade frictions with the several Western countries—along with a tumultuous post-pandemic global economy—has stymied demand for Chinese exports as the country struggles to recover trade volume to its pre-COVID levels. At present, a low global demand invariably impacts China’s domestic manufacturing activity (Reuters, May 31). The PRC’s exports fell by 7.5 percent year-on-year in May and by 12.4 percent in June (Reuters, 2023, July 13 and SCMP, July 18).

A second indicator for China’s poor economic performance is a severe drop in factory gate prices. Reflecting a downturn in the country’s manufacturing sector, China’s factory gate prices are falling at the fastest pace in seven years (Nikkei, 2023, July 10). Low factory gate prices suggest that demand has fallen, driving down prices for finished goods. Typically, companies will cut production of goods if the factory gate price falls below the cost of manufacturing, resulting in mass layoffs and a subsequent rise in unemployment. As consumer prices and employment remained flat in June, the Chinese economy is at risk of spiraling into deflation (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023, June 15).

A third strong indicator of China’s economic growth is its manufacturing PMI, which indexes the prevailing direction of the country’s manufacturing sector. In May, China’s manufacturing PMI fell to a five-month low of 48.8—a score below 50 signifies a contraction (State Council Information Office, May 31). Non-manufacturing PMI is also trending downward, falling from 56.4 to 54.5 in the span of one month (China Daily, May 31). In June, the PMI experienced a slight increase of 0.2 coming in at 49 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023, July 1). However, the Producer Price Index (PPI) for manufactured goods continued to trend downward. The PPI was down 4.6 year-on-year in May (Xinhua, 2023, June 9) and experienced a 5.4 percent drop in June (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023, July 11).

The fourth data point is the devaluation of the yuan. Since the start of last year, the yuan has depreciated by 4.7 percent relative to the US dollar (SCMP, June 20). A key strategic objective of Beijing’s monetary policy is keeping the value of the yuan in close proximity to the seven-dollar threshold. This goal was met with significant setbacks as China’s economy continued to falter, causing the currency to depreciate well past the seven-dollar threshold in May (The Business Times, May 17). Despite these warning signs, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) still refrained from intervention in the foreign exchange market to stabilize the yuan (SCMP, June 20).

The fifth variable leading to China’s considerable economic downturn is the decline of the real estate sector. One of the largest drivers of the economy, the property sector accounts for about one third of China’s total investment. In the first half of the year, property investment was down 7.9 percent (SCMP, July 18). In June, China’s 100 largest developers saw their property sales fall by an annualized rate of 28.1 percent, while new home prices in most major cities remained largely flat. The S&P Global Ratings forecast this year’s property sales to come in 30 percent below their 2021 peak (SCMP, July 17). Even prior to the onset of the pandemic, the property sector in China was grappling with a considerable debt bubble. As China’s total debt to GDP ratio was already 280 percent in the first quarter of the year, the continual decline of the property sector will only serve to exacerbate this trend (SCMP, July 17; Straits Times, November 1, 2022). This year, developers are facing $141 billion worth of bonds coming due (Caixin, January 10). Furthermore, Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFV)—land sales facilitated by provincial governments—are responsible for an additional $9 trillion of debt (Blomberg, June 2). Both real estate developers and local governments are at high risk of defaulting.

The Blame Game

As the economy continues to decline, official state discourse has redirected blame onto external actors. China’s private sector is a case in point. The central government has already shown signs of scapegoating private enterprises, attributing rising housing prices to greed and speculation, as well as criticizing large corporations for the country’s wealth inequality. To promote Xi Jinping’s push for “common prosperity” and bridge the wealth gap, Beijing has called for an austerity drive among China’s financial firms (Reuters, June 18). Clamping down on bourgeoisie excess, the central government is strongly encouraging the employees of financial firms to dress more “down to earth”, refrain from extravagant banquets, and avoid flashy jewelry and designer clothes. Additionally, several finance firms are cutting the salaries and annual bonuses of their employees.

While the financial sector is facing disciplinary measures, technology companies have recently been subject to preferential treatment. On July 12, Premier Li Qiang pledged for the central government to cultivate a direct line of communication with technology firms to “stay up on corporate difficulties and concerns” (SCMP, 2023, July 12). Notably, this statement comes at the same time the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) endorsed the investment projects of several leading technology firms (SCMP, 2023, July 12). As the technology sector is one of the largest drivers of economic growth, it is likely China’s central leadership wants to maintain international competitiveness by giving these companies a relative degree of maneuverability. Notionally, this development signals that the 2020 regulatory “tech crackdown” that targeted Alibaba and Tencent is coming to an end, at least for the time being (Reuters, July 12).

The central government is also holding young graduates accountable for the country’s economic slowdown. Facing major economic headwinds, Chinese youth are struggling to find employment. In May, youth unemployment hit a record 20.8 percent (National Bureau of Statistics, April 19; SCMP, July 18). The Party narrative attributes rising youth unemployment to the supposedly unrealistic expectations of recent graduates. According to this perspective, Chinese youth should be willing to accept blue-collar occupations regardless of their educational credentials (Global Times, June 25). In addition to increasing public sector employment, the government is encouraging college graduates who are struggling to find work to assume manual labor jobs. To this end, Xi has urged the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of China (CYLC) to rally the young generation, cultivate their “grit,” and remind them that they represent China’s future (China Daily, June 27).

Policy Tools for Economic Recovery

To address the flagging economy, Xi is calling for consumption-led growth. This solution appears poorly tailored to the Chinese market; household spending accounts for just 38 percent of China’s GDP, while the number is closer to 68% in the rest of the world (Market Insider, 2023). If the economy slips into deflation—generally a consequence of unemployment rising and wages falling—household consumption will significantly decline. Even assuming a more optimistic outlook, altering Chinese consumers’ spending habits will likely remain a challenge given China’s economic uncertainty. Therefore, it is unlikely that increased consumption and natural market factors will prevent the Chinese economy from further decline. Consequently, Beijing will likely implement some form of state intervention to stimulate growth.

To this end, the central government could engage in open market operations. This approach involves manipulating the money supply and influencing interest rates by buying and selling government bonds on the open market. Additionally, there could be further cuts to bank reserve requirements and key lending rates. The PBOC could also provide medium-term funding to commercial banks in order to manage liquidity and support the country’s economy. Zou Lan, the head of the PBOC monetary policy department, said that his group will employ countercyclical adjustments to counteract fluctuations in economic activity and mitigate the negative impact of economic cycles, resulting in sustainable growth (Reuters, July 14). Zou went on to suggest that there might be some changes made in property policies as he felt there was room for “marginal optimization”. Special loans worth $28 billion have been extended to developers to finish pre-sold housing projects. Originally, the cutoff date for these loans was March of this year, but it will be extended to May of 2024 to help keep the property sector afloat (Reuters, July 14).

Another core challenge the central government will have to address is youth unemployment. The State Council released a 15-point plan to help match graduates with jobs. In addition to skills training and entrepreneurship, the plan includes increasing the number of employees at state-owned enterprises (State Council, April 26). Elevating the role of SOEs in the Chinese economy—a relatively inefficient sector compared to private enterprises—will likely fail to address the root cause of China’s sluggish growth. While expanding state-run businesses can create new employment opportunities, it will likely struggle to generate sustainable economic growth. In practice, hiring more people to do the same amount of work effectively amounts to an advanced form of welfare. While China has developed to the extent that it can produce over 10 million college graduates per year, successfully providing these graduates with employment outcomes that align with their qualifications remains a systemic challenge.

Conclusion

Despite the promotion of state-led initiatives to accelerate the recovery of China’s economy, several structural obstacles to China’s economic growth remain. Moving forward, Beijing will continue to struggle with three long term obstacles that will likely impede growth: a declining birthrate, a massive debt bubble, and a global economy that is becoming increasingly less receptive to Chinese trade and investment. Births in China this year are projected to be 8 million, down from 9.4 million last year (SCMP, May 30). Combined public and private debt now exceeds 300 percent of GDP (South China Morning Post, May 30). Additionally, China’s external environment is increasingly volatile. A central theme at the recent G7 summit was “de-risking,” as the world’s largest economies are seeking to decrease investment and trade tied to the Chinese market (Nikkei, May 20).

In conclusion, it appears that the Chinese economy will recover this year, but the recovery will be much more modest than originally anticipated. A slow recovery—coupled with issues such as youth unemployment, a lack of high-value service sector activity, an acute debt crisis, and China’s declining international reputation—suggest that the era of rapid growth is over. Moving forward, rather than experience a robust seven or eight percent GDP growth rate each year, the Chinese economy appears to be transitioning to a new phase of slower, more modest growth. The PRC’s future trajectory will likely be influenced by both the capacity of the central government, and the average Chinese consumer, to navigate this new economic reality.