Xi’s New Year’s Speech Dismisses Difficulties

Publication: China Brief Volume: 24 Issue: 1

By:

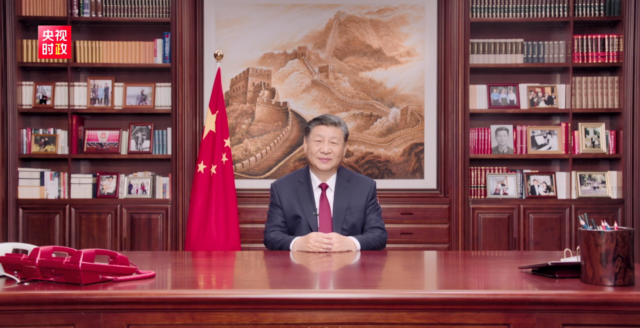

On New Year’s Eve, a prerecorded address from Chinese President Xi Jinping was broadcast across the Party’s global network of official media outlets (Youtube, December 31, 2023). The speech is an annual tradition, delivered from behind a wooden desk in rhetoric that is at once paternalistic and triumphalist, in which Xi surveys the high points of the outgoing year and looks to the year ahead. The form of this year’s set-piece was no different, but the content departed from previous years in ways that are indicative of Xi’s shifting priorities, and the Party’s growing concerns about the state of the nation.

The most significant section of the speech addressed the economic difficulties that China has weathered in the last year:

“On the road ahead, trials and hardships [lit. ‘wind and rain’] will be the norm. Some enterprises are facing pressures, some of the masses are encountering difficulties finding jobs and meeting basic needs, and some places have hit by floods, typhoons, earthquakes, or other natural disasters (有风有雨是常态 。一些企业面临经营压力,一些群众就业、生活遇到困难,一些地方发生洪涝、台风、地震等自然灾害).”

Any acknowledgement of social issues is a rarity in such speeches, and a departure from previous years. The tenor of Xi’s New Year’s addresses has shifted over the years, and particularly following the outbreak of the pandemic. (Consider, for instance, his 2020 address, which is completely devoid of negative energy (CGTN, December 31, 2019)). Broaching these topics directly, as in this year’s speech, is novel. Some commentators have drawn comparisons to Mao apologizing in 1960 for his own mistakes, and speculated that this indicates Xi is facing pressure from within the Party (VOA, January 4). Even if this feels hyperbolic, it gives a sense of how unusual such an admission is. The choreography of this moment in the speech is also fascinating. Throughout the rest of the address, the camera is either trained on Xi directly, or at a slight angle. However, the camera cuts back to a wider shot at a larger angle just at the very moment where Xi is about to refer to the difficulties facing the masses—the only such instance in the speech. This not only breaks up the sentence, it also creates a visual distance between Xi Jinping and the content of his words. The obfuscation of any culpability on the part of the Party is then enhanced by packaging this together with the natural disasters that have befallen China this year.

A substantial portion of the speech focuses on international affairs. This section has grown over Xi’s tenure. He rattled off a list of important international events that China hosted, including the Chengdu FISU World University Games, the Hangzhou Asian Games, the China-Central Asia Summit, and the Third Belt and Road Summit on International Cooperation. This is a contrast from earlier years, when mentions of the world beyond China were restricted to a small paragraph at the end of the speech or included references to commemorating the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression and the Nanjing Massacre—something that has disappeared in the last few iterations. For instance, Xi’s 2015 address proudly touts its assistance with containing the Ebola epidemic in Africa and assuaging a water shortage in the Maldives as the best examples of its outreach in the previous year (Manchester Consulate, January 4, 2015). Clearly China’s capacity to match its level of ambition has increased dramatically in the intervening years. But it is also clear that Xi has “full confidence in the future” for those ambitions, despite the “headwinds” that he briefly alludes to.

There is an additional possibility for Xi’s insistence on focusing China’s stature beyond the PRC’s borders: To divert attention from the problems at home. Xi finishes the speech by emphasizing that his fundamental goal is to improve the lives of ordinary people. He elaborates by citing children’s education, opportunities for young people, and elderly care as three key areas to strive to improve. However, these are not necessarily areas where Xi’s China has made significant progress: China is the least educated middle-income country in the world, youth unemployment is at dangerously high levels, and the healthcare system has been plagued by corruption (East Asia Forum, March 30, 2023; China Brief, July 21, 2023; China Brief, October 6, 2023). Interestingly, while Xinhua’s translation of this piece calls these issues “a top priority of the government,” Xi merely stated that they were “national affairs (国事).” His subsequent enjoinder that “everyone must work hard together to deal with these matters (大家要共同努力,把这些事办好)” again deflects responsibility for any shortcomings from the Party or his government.

The rest of the speech, in and among the stock Party phrases, was a mixture of lauding technological achievements from the past year and mentions of some of Xi’s personal favorite topics. The former included the—by now annual—mention of the Comac C919 aircraft, as well as China’s new large cruise ship, the Shenzhou spaceships and Fendouzhe deep-sea submersible, the latest Chinese-made mobile phones, new energy vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and photovoltaics. The latter encompassed references to Xiong’an New Area (Xi’s pet smart city project outside Beijing), soccer through the summer “village super league (村超)” in Guizhou, and early Chinese civilization (such as the archeological sites of Erlitou, Sanxingdui, and Liangzhu). A mention of the “historical necessity (历史必然)” of national reunification, which Xi links explicitly to “national rejuvenation” echoed statements made in previous years. The integration of the “Greater Bay Area,” another core project that Xi references, undergirded the PRC’s designs on Hong Kong in the last decade. This kind of economic and infrastructural integration is a key part of the PRC’s strategy for reunification, as well as its ambitions further beyond its borders.

Some of the context surrounding Xi’s speech provides additional indications of the state of his China. On the home front, it appears that in many city centers, New Year’s Eve celebrations were abruptly canceled. Fireworks displays were prohibited (officially over concerns about air pollution), with police confiscating and apprehending those who attempted to set them off and firefighters preemptively dousing them on the street before firing water cannons to disperse the crowd. Big screens in multiple cities were abruptly switched off with seconds to go before midnight, to the surprise and consternation of many of those assembled (officials in Yantai, Shandong Province cited “security control requirements”). In Shijiazhuang, a drone display was shut down, with the organizer prostrating himself on the floor in apology, before being marched off (Chinadaily, December 31, 2023; Youtube, January 2). Meanwhile, the two biggest headlines for the PRC’s international outreach on New Year’s Day were an announcement of Xi exchanging New Year greetings with Russian President Vladimir Putin and designating 2024 as China-DPRK Friendship Year alongside Kim Jong Un (Xinhua, December 31, 2023; Xinhua, January 1).

That so much of Xi’s speech wraps itself in the triumphalist rhetoric of perpetual progress underlines the ironclad commitment to achieving the goals that he has spelled out in numerous other speeches over the past decade. Nods to “Chinese-style modernization,” the “new development concept,” and “constructing a new development model” are all redolent of the hubris of someone who sees China on the right track. There are chinks in the armor of Xi Jinping’s China as this context and his brief mea culpa makes clear. But he is still unambiguous that China is a great country (“伟大的国度”), and that it will emerge stronger having weathered the current storm (“中国经济在风浪中强健了体魄、壮实了筋骨”).