Zhou’s Fall About Institutions, Not Personalities

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 15

By:

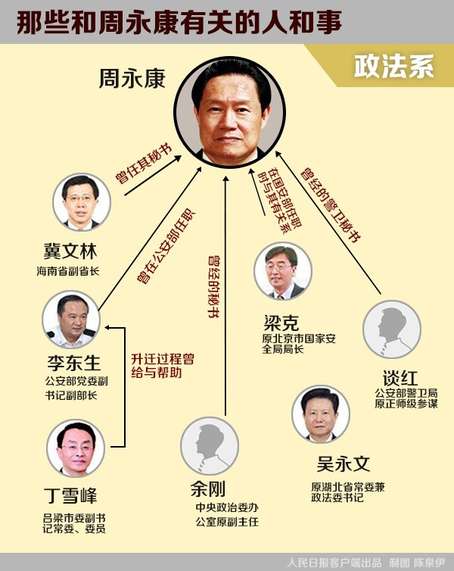

On Tuesday, Chinese official media confirmed the long-anticipated arrest of Zhou Yongkang (Xinhua, July 29). Zhou, a former member of the Politboro Standing Committee and head of China’s state security apparatus, is the first member of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) highest echelon to fall from power since and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crisis, and the first ever to be charged with corruption (Zhao Ziyang, CCP General Secretary at the time of the crisis, was placed under informal house arrest). The following day, the Politboro confirmed rumors that the fourth plenary session of the Central Committee in October will focus on “governing the country according to law,” strongly suggesting that China’s top leaders aim to reform legal institutions to consolidate the effects of the ongoing anti-corruption campaign (People’s Daily, July 30).

Zhou’s arrest has been definitively interpreted in Chinese state media as proof that “no matter how high their post or how long their service, all cadres must answer to party discipline and the law,” as a front-page editorial in People’s Daily put it (People’s Daily, July 30). So far, every story longer than Xinhua’s two-line announcement of the arrest has emphasized this point (see also People’s Net, July 29 and July 30; Caixin, July 30).

Who Targeted Zhou?

Meanwhile, many foreign analysts have interpreted the bagging of China’s largest “tiger” yet as evidence of Xi’s personal power, attributing it either to factional conflict or a determination to reform the party. While Xi’s anti-corruption campaign played a major role in the lead-up to Zhou’s arrest, there is also evidence that a consensus against him emerged among Party leaders and elders before Xi took office in 2012, highlighting an important determinant of Xi’s power that has not been sufficiently examined: the striking unity of China’s top leaders behind Xi’s reform agenda.

Xi appears to have had support to pursue Zhou in the first months of his term, targeting officials linked to the former security czar at the outset of his anti-corruption campaign and before assuming the office of President (NTD TV, February 11, 2013). Furthermore, at the time he became General Secretary of the CCP, the Party reduced the membership of the Standing Committee from seven to nine—placing Zhou’s successor on a lower rung of the CCP hierarchy and placing an official perceived as an un-ambitious administrator at the head of the Ministry of Public Security (China Brief, February 1, 2013). These moves—decided by a broad but poorly understood group of Party elders and retiring leaders—sought to weaken the office as well as the man, strongly suggesting a consensus that the security czar had accumulated too much power. This explanation of Zhou’s downfall suggests that we should look past Xi when explaining the dramatic move—that the source of this and other high-profile reform drives lies not only in the personal power of China’s President, but in agreements made among China’s top leaders.

Helping Cadres Interpret Zhou’s Arrest

While speculation about Zhou has been censored for the past year, Chinese information authorities have permitted guided discussion of the announcement, and People’s Net has created a landing page for stories about the arrest (People’s Net, “Zhou Yongkang Under Investigation for Grave Disciplinary Violations”; Wall Street Journal, July 29). The People’s Daily editorial used the opportunity both to explain the reach of the anti-corruption campaign and to remind readers of the reasons for it, linking the campaign to internal and external threats to party rule (People’s Daily, July 30).

The first section of the editorial covers what it is by now familiar ground, using Zhou as an example to demonstrate that no one is above the law. But the third, and longest, paragraph reminds readers that “To rule the nation we must rule the party; to rule the party we must be severe,” arguing that the party’s survival depends on widespread cooperation with a campaign that asks officials to give up many of the privileges of office and to tolerate the danger of arrest. The editorial argues that “the party is confronted by acute tests and dangers,” citing the “new situation”—a recent interpretation of international affairs that emphasizes the need for transformation in response to external threats and opportunities (see “A ‘New Situation:’ China’s Evolving Assessment of its Security Environment,” in this issue of China Brief). Except for discussions of corruption, the “new situation” phrase is used exclusively for discussion of international affairs, continuing a pattern of tying corruption to external threats to build a “sense of crisis” (see China Brief, August 23, 2013, May 23, 2013).

Putting Cadres on Their Best Behavior—and Making it Last

While Zhou’s arrest completes an investigation that lasted for over a year, Xi has made it clear that this is not the end of his fight against corruption (see China Brief, July 3). Indeed, a commentary by the Guoping (“National Peace”) column framed the arrest as a move to clear out the obstacles to further reform (People’s Net, July 31). However, a purge cannot last forever, and without institutional reform progress on discipline is likely to be lost.

The announcement that the main topic of October’s Fourth Plenum will be “governing according to law” confirms that reform of the legal system is the next step in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. While officials are currently on their best behavior, Xi appears to hope that more independent oversight will make temporary changes into permanent practices. There is little sign of what these reforms will look like, although legal reform pilot programs launched in four provinces in June may suggest a focus on reducing political interference in court (China Brief, June 19). Plenary sessions—such as last year’s Third Plenum, focused on economic reform—are used to set major goals; the decision is likely to sketch out broad principles for reform and to begin a long process of implementation.

With the arrest of a major leader in a continuing, and massive, purge, and constant reminders that the stakes of the struggle against corruption are nothing less than the survival of the party, Xi and his colleagues have sought to generate a period of crisis in which major changes are possible. The question to remain is whether this political window is wide enough—and will stay open long enough—to allow systemic change to take root.