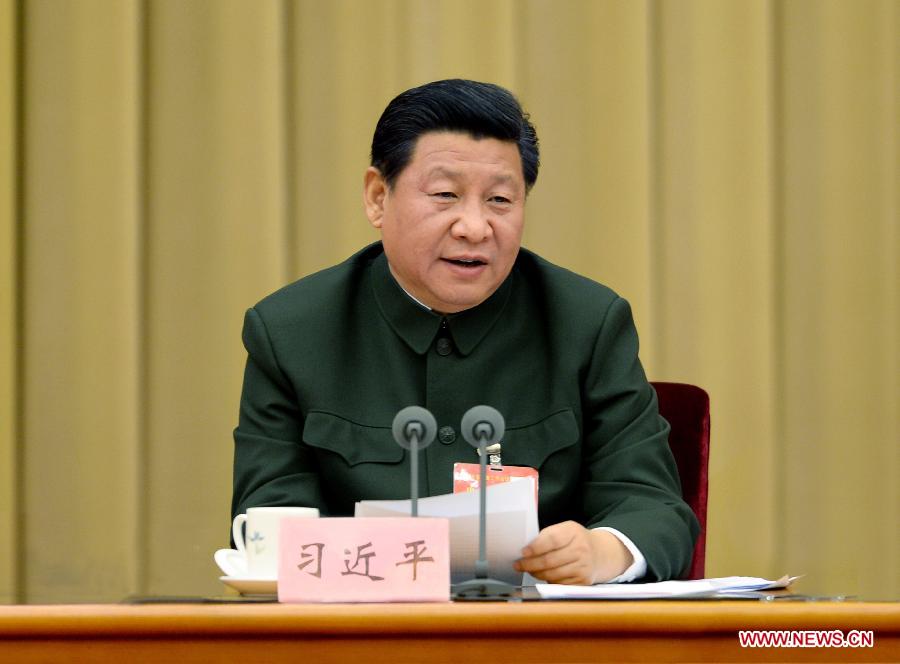

A Modern Cult of Personality? Xi Jinping Aspires To Be The Equal of Mao and Deng

Publication: China Brief Volume: 15 Issue: 5

By:

Having been in office for just over two years, President Xi Jinping has already laid claim to being the third most powerful politician of post-liberation China, just after Chairman Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s economic reforms. Having gained control over what Chinese commentators call “the gun and the knife”—a reference to the army, police, spies and the all-powerful graft-busters—the Fifth-Generation titan is quickly growing his body of dictums and instructions on ideology, governance and related issues. The zealousness with which the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) propaganda machinery is eulogizing Xi’s words of wisdom smacks of the cult of personality that was associated with the Great Helmsman himself, Mao.

“The Spirit of Xi Jinping” Haunts CCP Ideology

What Xi’s publicists call “the spirit of the series of important speeches by General Secretary Xi Jinping” (xijinping zongshuji xilie zhongyao jianghua jingshen) is being accorded the same status as Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. It was at the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee held last October that “the Spirit of Xi Jinping” was elevated to the same level as the teachings of Mao and Deng. The Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Advancing Rule of Law, which was endorsed at the Fourth Plenum, was the first top-tier official document that put “the spirit of the series of important speeches by General Secretary Xi Jinping” on par with “Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the important thoughts of ‘Three Represents’ and the ‘Scientific Outlook on Development,’” which were deemed guiding principles of the Party and state (see China Brief, November 20, 2014; People’s Daily, October 29, 2014 Xinhua, October 23, 2014). The “Three Represents” and “Scientific Outlook on Development” are considered major theoretical contributions of former presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao respectively. Partly owing to Deng’s advocacy of the virtues of a collective leadership, however, Jiang and Hu are not identified in Party documents as the authors of their well-known mantras. Indeed, Politburo member Wang Huning, who served as a political aide to Jiang, was considered to have played a big role in the formulation of the “Three Represents” doctrine. And Wen Jiabao, who was premier during the Hu era, was among a handful of senior cadres who served to substantiate the “Scientific Outlook on Development” (Southern Metropolitan Weekly, November 26, 2013; People’s Daily, October 20, 2008). Xi’s apparent ability to persuade senior cadres to salute “the Spirit of Xi Jinping” (xijinping jingshen) testifies to a return of the tradition of strongman-style politics in CCP cosmology. Through releasing at least four anthologies of his speeches and writings over the last two years, Xi has also broken the long-established tradition that Party leaders publish books only after their retirement (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], February 5; Zhejiang Online [Hangzhou], April 8, 2014).

The glorification of the Spirit of Xi Jinping began barely one year after Xi became Party boss and commander-in-chief at the 18th Party Congress in late 2012. In December 2013, the People’s Daily published nine commentaries summarizing Xi’s instructions on areas including “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” the Chinese dream, economic and political reforms, culture, foreign policy and Party construction. Xi’s brilliant talks and instructions, said People’s Daily, represented “new ways of thinking, new perspectives, new conclusions and new demands [on the Party and nation].” The Party mouthpiece added that Xi had “grasped the new demands of the era as well as the new expectations of the masses” (Thepaper.cn [Shanghai], October 24, 2014; People’s Daily, December 31, 2013).

Building a Cult of Personality

The superlatives have become progressively more grandiloquent. The Guangming Daily noted, in late 2014, that the Spirit of Xi Jinping consisted of a body of “scientific theory and practice …that would open up new vistas for the Party and country.” Xi’s instructions, the official paper noted, amounted to “new chapters in the Sinicization of Marxism.” According to Report on Current Affairs, a journal run by the Propaganda Department, the Spirit of Xi Jinping “has provided a profound answer to major questions of theory and practice regarding the development of the Party and state in the new historical era.” “It has enriched and developed the scientific theory of the Communist Party,” Report added (Report on Current Affairs [Beijing], January 13; Guangming Daily, December 6, 2014). Moreover, relevant heads of departments and regional leaders have—in a throwback to ideological campaigns of the Maoist era—competed with one another in a ritualistic display of fealty to the patriarch. This biaotai (“public airing of support”) was led by Director of the CCP Propaganda Department Liu Qibao, who noted that all Party members should absorb and make use of the “rich content, profound thinking and superb arguments” contained in the Spirit of Xi Jinping. The President’s instructions, Liu added, had “enabled the Party and state to attain new achievements, established a new style, and opened up new possibilities.” Zhejiang Party Secretary Xia Baolong, deemed a Xi protégé, was among provincial officials who sang the praises of the Spirit of Xi Jinping. In a talk last year, Xia urged his Zhejiang colleagues to use Xi’s words of wisdom “to arm their brains.” “The more we know about [the Xi spirit], the more we are convinced and the more resolute we will be when implementing it,” he noted (People’s Daily, May 16, 2014; Zhejiang Daily, April 2, 2014).

The Tenets of Xi’s “Spirit”

Just what does the Spirit of Xi Jinping consist of? It is true that in the past two years, the President and Commander-in-Chief has come up with eye-catching initiatives on the foreign policy and military fronts. For example, he has unveiled the New Silk Road Economic Belt to boost links with Central Asian states as well as the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road to woo Southeast Asian and South-Asian countries, ranging from Indonesia and Malaysia to Sri Lanka and Pakistan (see China Brief, February 20; Xinhua, February 5; New Beijing Post, December 10, 2014).

On the domestic front, however, Xi has yet to formulate mantras or policies comparable, for example, to the “Three Represents” or “Scientific Outlook on Development.” Late last month, the People’s Daily and other state media began extolling the virtues of the so-called “Four Comprehensives,” namely, “comprehensively building a moderately prosperous society, comprehensively deepening reform, comprehensively governing the nation according to law, and comprehensively administering the Party with strictness.” The People’s Daily commentary pointed out that the “Four Comprehensives” were “a unique system of ideas that is built on past [party dogma] and that demonstrates boldness in innovation.” “It is an innovative strategy in governing the party and country that [shows the party’s ability to] make progress with the times,” the paper added. “It is a synthesis between Marxism and the practice [of governance] in China” (People’s Daily, February 24; Xinhua, February 26).

While the “Four Comprehensives” has been described as a “new political theory,” it seems a mere amalgamation of slogans and dictums that have been used by top cadres since the end of the Cultural Revolution. “Building a moderately prosperous society” was the rallying cry of Deng Xiaoping when he kick-started economic reform in the early 1980s. And both ex-presidents Jiang and Hu had waxed eloquent about deepening reform and running the country according to law (Ming Pao, February 27). By and large, Xi is still better known as a conservative ideologue who urges his 1.3 billion countrymen to cleave to socialist orthodoxy rather than breaking new ground. Hence, his famous insistence that Party members and citizens alike should renew their “self-confidence in the theory, path and institutions” of socialism with Chinese characteristics. According to an article in a journal under the CCP Central Party School, the “Xi Jinping Spirit” consists of one prime goal—“attaining the Chinese dream”; and two fundamental points—“comprehensively implementing reforms and upholding the line of the masses” (Central Party School Net, August 8, 2014). This seems a restatement of late patriarch Deng’s famous mantra about the Party sticking to the central task of building up the economy while pursuing the two objectives of promoting reform and the open-door policy on the one hand, and upholding the Four Cardinal Principles of orthodox socialism on the other.

It is perhaps due to the rather mundane contents of the Spirit of Xi Jinping that the Party’s ideological and propaganda machinery has gone into overdrive in order to give it as much publicity as possible. The Party-state apparatus is imposing a uniformity of thought among Chinese intellectuals and college students. Early this year, the General Office of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council General Office issued a document entitled “Opinions Regarding Further Strengthening and Improving Propaganda and Ideological Work in Universities Under New Conditions.” The nationally circulated document urged college administrators and teachers to “earnestly insert the theoretical system of Chinese-style socialism into teaching materials, the classrooms and the brains [of students].” It added that “the ideological and political qualities of teaching teams must be raised” and that “the Party’s leadership over propaganda and ideological work in colleges must be enhanced” (People’s Daily, January 20; Xinhua, January 19).

In an address on the new thought-control campaign in colleges, Minister of Education Yuan Guiren noted that “there is no way that universities can allow teaching materials containing Western values and precepts into our classrooms.” He warned that teachers and students “should absolutely be forbidden to attack or speak ill of Party leaders or to smear and disparage socialism.” The connection between this draconian ideological crusade and the no-holds-barred adulation of President Xi was made clear when Yuan played up the imperative that “we must let the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s series of important speeches get into teaching materials, classrooms and [students’] brains” (People’s Daily, January 29; Xinhua, January 29).

Xi’s Cult of Personality Infiltrates the PLA

A parallel quasi-personality cult around Commander-in-Chief Xi is being constructed in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). For the first time in the history of the military forces, Xi’s loyalists are pushing “the CMC Chairman Responsibility System.” This means that the CMC chairman alone can make policies and issue instructions on defense-related issues. As the official Liberation Army Daily explained, the responsibility system also means that PLA officers and soldiers pledge to “resolutely follow Chairman Xi’s orders, resolutely execute Chairman Xi’s demands, and resolutely fulfil the tasks laid down by Chairman Xi” (Liberation Army Daily, January 28; China.com.cn, January 19). It is understood that Xi is pushing this “responsibility system” to rectify perceived lapses in the leadership of his two predecessors as CMC chairman: former presidents Jiang and Hu. Not being professional soldiers, Jiang and Hu by and large allowed senior generals sitting on the CMC to make decisions on areas including strategy, personnel, and research and development of weapons. The “CMC Chairman responsibility system” could reflect Xi’s distrust of generals who owed their promotion to ex-CMC chairmen Jiang and Hu (Ming Pao, January 19; Radio Free Asia, December 30, 2014). Since late 2014, Xi has promoted a rash of generals from the Nanjing Military Region in coastal China, whose top brass are cronies of the President when the latter served in regional posts in Fujian and Zhejiang (see China Brief, January 9).

Xi’s ambition to become the equal of Mao and Deng will be dramatically illustrated during the military parade scheduled to take place at Tiananmen Square on September 3. The ostensible reason for this year’s demonstration of China’s hard power was to mark the 70th anniversary of the “triumph in the global struggle against fascism,” which is the CCP’s phrase to describe the surrender of the Japanese Imperial Army in 1945. The military parade, which will feature Xi inspecting the PLA’s latest hardware such new generations of stealth aircraft and ballistic missiles, will above all buttress the Fifth-Generation leader’s status as what liberal Chinese intellectuals call “the Mao Zedong of the 21st Century.” The extravaganza is yet another example of Xi breaking with tradition in order to project his own authority. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, such extravaganzas have only been held three times—in 1984, 1999 and 2009—to mark important anniversaries of the founding of the People’s Republic (Ta Kung Pao [Hong Kong], February 15; New Evening Post [Beijing], January 28). Moreover, Jiang presided over the Tiananmen military parade in 1999—and Hu masterminded the grand spectacle in 2009—three years before his retirement as general secretary. When Xi reviews the troops this September, it will be two months shy of the third-year anniversary of his coming to power.

Liberal Criticism of Xi’s Cult

The return of a Mao-style cult of personality has drawn criticisms from the nation’s dwindling number of outspoken liberal intellectuals. Well-known public intellectual Zhang Lifan, a former historian at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, deplored the near-deification of Xi by the media. “We are not sure whether Xi is happy about the political packaging,” Zhang said. “But this packaging has gone overboard… to the extent that Xi has become an omnipotent person.” Li Datong, a liberal news commentator, said he was “disturbed by the evil trend of a personality cult being built around Xi.” “The systems and institutions of the CCP are bad, and traditional ways of thinking could prompt Xi to repeat old mistakes [of the Maoist era]” (VOA News, January 18; Deutsche Welle Chinese, October 25, 2014). Ding Wang, a veteran Hong Kong-based Sinologist, sees the contours of the resurrection of a Mao-style “one-voice chamber.” “Xi the new emperor is wielding the knife to stifle Western ideas and to impose orthodoxy,” Ding wrote. “The clock is being turned back and we seem to be in the midst of a quasi-Cultural Revolution” (Hong Kong Economic Journal, February 5; Apple Daily [Hong Kong], February 3).

Perhaps more important is the fact that in spite of the apparent popularity of the theory of neo-authoritarianism—that reforms can be expedited if they are being pushed by a really authoritative patriarch—there is no evidence to show that the party-state apparatus is “comprehensively deepening reform” in an efficient manner (Phoenix TV, January 8; Radio Free Asia, December 19, 2013).Take, for example, the establishment of Free Trade Zones (FTZ), which is one of the most radical proposals endorsed by the Third Plenary Meeting of the Central Committee in November 2013. Despite pledges that close to 20 FTZs will be set up around the country, so far only four have been announced. And the Shanghai FTZ, a prototype experimental patch set up as two months before the Third Plenum, has been viewed with skepticism if not frustration by Western corporations easy to break into areas that are monopolized by well-connected Chinese firms (see China Brief, February 20; 21st Century Net [Guangzhou] September 27, 2014; Phoenix TV, September 24, 2014). The same foot-dragging seems to be the case with the reform of the 100-odd yangqi, or centrally-controlled state-owned-enterprise conglomerates. The only Xi dictum which seems to be working with these mammoth state monopolies is that the salaries of senior managers would be drastically cut in line with the strongman’s clean-governance crusade (Changsha Evening News, [Hunan], September 3, 2014; South China Morning Post, August 31, 2014). The lack of obvious achievements for economic reform has reinforced the belief that Xi is consolidating power out of a Maoist-style self-aggrandizement rather than a genuine commitment to Deng-style liberalization.