Conceptualizing “New Type Great Power Relations”: The Sino-Russian Model

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 9

By:

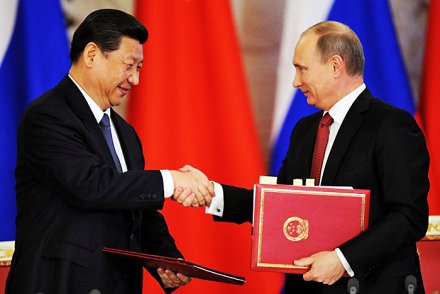

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping first proposed establishing “New Type of Great Power Relations” (NTGPR) between the U.S. and China, many have been discussing the true meaning of the phrase for Washington [1]. However, the NTGPR concept is not purely Xi’s policy invention, but a slightly refined version of a phrase long used in Beijing’s relations with Moscow. With attention on Sino-Russian relations during the recent Crimea crisis, many analysts raised questions regarding actual Chinese and Russian strategic alignment. What was overlooked in the ensuing analysis is the very relevant twenty-year history of Sino-Russian agreement on core strategic principles that govern their NTGPR (Seeking Truth, April 16, 2013). Careful analysis of this strategic concept illuminates two broad themes.

First, NTGPR is a well-developed, coherent outgrowth of Chinese foreign policy with a history of use and refinement in Sino-Russian relations since the mid-1990s. Sino-Russian joint statements articulate the concept as a means to stabilize their relationship and establish a “new international order” to shape U.S. international behavior.

Second, China views Sino-Russian NTGPR as the “paradigm” for a concept that allows Beijing to orient itself and interact with other great powers within the post-Cold War international order. With U.S. adoption of NTGPR at last year’s Sunnylands summit, China seeks to apply the same concept to the Sino-U.S. case, with the same expectations – expectations the U.S. has not fully understood and likely could not accept.

This article will address the main principles of NTGPR articulated as framing Sino-Russian relations and discuss the implications for Washington.

Words Matter

The phrase “New Type Great Power Relations” is not simply rhetorical flourish, it is loaded with established meaning. In fact it is one of many Chinese terms of art—words or phrases with a specific meaning in a given context, a meaning usually different from common usage. These terms undergo extensive internal vetting before surfacing in Beijing’s diplomatic discourse as policy concepts. China seeks to gain foreign acceptance of such terms to establish “consensus” and legitimize China’s view of the world. Because these terms have meaning, the context in which they appear is critical to discerning that meaning.

“New Type Great Power Relations” in Theory and Practice

Development. Chinese analysts cite the end of the Cold War and the “profound and complex changes” in the international system since the mid-1990s as an opportunity allowing China to readjust its historically troubled relations with Russia through a “New Type of Relations” (NTR). For both, NTR offered a framework for stability in the relationship and a chance to refocus on development issues (Seeking Truth, June 16, 1995). Considering China’s strategic goal of “national rejuvenation” and Russia’s own post-Soviet recovery, China’s 14th Party Congress reaffirmed the need for a stable international environment to achieve those ends, and NTR became essential to foster those conditions (People’s Daily, October 21, 1992).

While Chinese analysts cite Gorbachev’s 1989 landmark visit to China as the beginning of NTR, they highlight Soviet acquiescence on China’s “three obstacles” in the preceding years as critical to setting the conditions for this development (International Studies, July 3, 1999) [2]. Chinese analysts cite Boris Yeltsin’s 1992 visit to Beijing as “laying the foundation” for NTR and were using the phrase prior to Jiang Zemin’s first use in a 1995 speech in Moscow declaring, “this New Type of Relationship is viable and will benefit not only the Chinese and Russian peoples, but also world peace and development” (Beijing Review, November 13, 1995; Xinhua, May 9, 1995).

The first codification of NTR was in the 1997 “Russian-Chinese Joint Declaration on a Multipolar World and the Establishment of a New International Order” stating, “no country should seek hegemony, engage in power politics or monopolize international affairs,” and that NTR were “important to establish a new international order” (Xinhua, April 23, 1997). The core principles of NTR codified in that joint statement (and many to follow) reflected growing concern of a post-Cold War order dominated by the United States as well as the downturn in their respective relations with the U.S. resulting from events such as the Tiananmen massacre, the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crises, U.S. military interventions, NATO expansion, and the war in Chechnya, among others.

NTR remained in official Sino-Russian statements until “Great Power” was added and adopted by both China and Russia in March 2013 — three months before use by President Obama at Sunnylands (Xinhua, March 22, 2013; White House, June 8, 2013). However, the language change did not accompany a change in meaning, and so an ongoing consensus on the core principles of NTGPR has helped Sino-Russian relations weather nearly twenty-years of policy disagreements.

These core principles align with the broad contours of Chinese foreign policy writ large, and are persistent throughout Sino-Russian leadership joint statements which reaffirm bilateral “consensus.” or “shared view.” What follows is a discussion of the explicit and implicit linkages and interactions between these core principles as articulated in Sino-Russian policies and rhetoric.

Accept multipolarity. Sino-Russian statements promote multipolarity as a means to facilitate a global distribution of power more suitable to their interests. Their leaders state a desire for their nations to rejoin the ranks of the great powers (the EU, United States, and possibly other BRICS nations) as geographically oriented “poles” in a new “just and rational” multipolar system absent U.S. hegemony (PLA Daily, September 1, 2003). As articulated, this principle reflects a desire for multiple great powers to jointly replace U.S. unipolarity through the exercise of greater authority in the conduct of international relations in this new system.

Acknowledge spheres of influence. Implicit in NTGPR is recognition of the right of great powers to a peripheral area of interests commensurate with their status as “poles” in the new multipolar order. President Medvedev’s 2008 proclamation of a Russian “sphere of privileged interests,” and China’s objective of a “Harmonious Asia” (highlighted by last year’s Peripheral Diplomacy Work Forum) all reflect impulses toward achieving regional preeminence and the importance of peripheral interests in their respective policies (“Xi Steps Up Efforts to Shape a China-Centered Regional Order,” China Brief, November 7, 2013). In fact, Chinese commentary discussing Beijing’s ambiguous non-position on Russian intervention in Crimea acknowledged the “historical facts and complexity” surrounding the issue and explained, “major powers are undergoing a period of adjustment in the distribution of capabilities in their spheres of influence”—a clear nod toward Russian peripheral privilege (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, March 4; People’s Daily, March 1). For China, this aspect of NTGPR suggests that, on balance, great power peripheral interests seem to trump the touted principle of “noninterference.”

Defer to UN authority. Sino-Russian statements consistently portray their nations as fully supporting the UN as the touchstone for legitimacy in international affairs, and U.S. unilateralism as a threat to international stability. Sino-Russian statements tout this principle as essential to “equality” and the “democratization of international relations” and explicitly oppose the use of force or threat of force without prior approval of the UN Security Council— allowing them final say on political and military interventions counter to their interests (Xinhua, July 5, 2000). Chinese commentary asserts this principle as a means to counter “New Interventionism” (xinganshe zhuyi)—perceived Western involvement in “Color Revolutions” under the “cover” of human rights that could foster instability in China (Seeking Truth, April 16, 2013; Study Times, January 21, 2013). Last, Beijing consistently highlights what it deems to be U.S. “hypocrisy” of admonishing China for violating the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in maritime disputes, yet unwilling to ratify UNCLOS.

Accommodate core interests. The fundamental basis of NTGPR is to “safeguard one’s own national interests while respecting the national interests of the other country” (Beijing Review, April 7, 2006). This is reflected in explicit Sino-Russian support for the territorial integrity, sovereignty, and development path of the other, and refrain from condemning statements or demands regarding the other’s humanitarian practices or treatment of minorities in restive provinces (Xinhua, April 25, 1996). Each side also reaffirms the others chosen socio-economic development path and political system particular to their national condition, while rejecting the promotion of a “universal” value set or particular political system.

Enhance cooperation. China has sought to legitimize NTGPR through the expansion of and focus on areas of cooperation and more frequent high-level, bilateral exchanges to facilitate the joint management of key issues by the two powers. In the Sino-Russian case, this includes strategic coordination on regional issues and crises, alignment in the UN Security Council and other multilateral venues, and mutual support on affairs related to their core interests. It has involved regularizing high-level visits, creating strategic dialogues, and broadening cooperation on a spectrum of issues as well as eliminating “discriminatory practices” in these areas (Xinhua, March 22, 2013).

Adhere to a "New Security Concept” (NSC). In contrast to the post-WWII global collective security order where national interests are largely subordinated for the collective good, the NSC is articulated as a construct that subordinates customary international law to the accommodation of national interests. In this light, the NSC is a concert-like framework for great power security interactions in the new multipolar order absent exclusive alliances (Xinhua, August 1, 2002). Following Soviet acquiescence on China’s “three obstacles,” China and Russia developed new security dialogues, agreements on military confidence-building measures (CBM), delimited borders, and expanded military exchanges as part of the implementation of the NTGPR under the NSC (International Studies, July 3, 1999). Sino-Russian statements explicitly reject alliance politics and instead tout the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as the model of security cooperation under NTR (Xinhua, August 1, 2002).

Lessons for the United States

The conceptualization of Sino-Russian NTGPR has implications for how the U.S. approaches NTGPR with China. While a bilateral framework to avoid conflict is in both sides’ interests, reaching agreement on the core principles of NTGPR is problematic.

Common desire for stable relations. Agreement on NTGPR core principles has consistently and unambiguously been a prerequisite to stability in Sino-Russian relations. Russian acceptance of NTGPR was in Moscow’s interest in order to stabilize their borders, foster trade, and deflect what they saw as U.S. interference in their internal affairs during the post-Cold War transition. Beijing currently touts the relationship with Russia as being at historically high levels due to continued consensus on those core principles – this despite periods of friction and disagreement not reflected in their joint statements (Xinhua, March 22, 2013). However, where one side is perceived to defect from the core principles—as with Russian arms sales to, and energy exploration with Vietnam in the South China Sea (considered by Beijing as meddling within its sphere)—true problems begin to emerge in the relationship (The National Interest, April 7).

For the United States, Beijing is applying the NTGPR model consistently and for the same reasons: stability in bilateral relations. Similar to Beijing’s calculus following the Soviet collapse, China senses an accelerated power shift in Beijing’s favor relative to the United States since the 2008 financial crisis and is attempting to readjust relations with Washington (CICIR, February 28, 2013). In fact, NTGPR was first floated to a U.S. audience by State Councilor Dai Binguo speaking at the Brookings Institute in late 2008, but the phrase did not appear again for the U.S. until 2012 when NTGPR was first raised by Xi during his visit to Washington (Xinhua, December 12, 2008).

In the Sino-U.S. case, both sides consistently acknowledge the likelihood that instability in relations could lead to conflict, and NTGPR is meant to avoid that outcome. For China, U.S. adoption of NTGPR is preferable over conflict as a solution to rectify the “contradiction that exists between a U.S. preference for unilateralism and China’s strategy” of establishing a new international order (China Business News, December 27, 2013). At Sunnylands, Xi was explicit: “China and the United States must find a new path— one that is different from the inevitable (emphasis added) confrontation and conflict between the major countries of the past…the two sides must work together to build a New Model of Major Country Relationship” (White House, June 8, 2013). For Beijing, U.S. acceptance of NTGPR translates into expectations regarding U.S. acceptance of the underlying principles— acceptance that is necessary to avoid conflict.

Differing views on core principles. A look at some persistent Chinese policy objectives illustrates Washington’s difficulty aligning with the core principles of NTGPR absent major changes to its foreign policy. While Beijing has not explicitly asked for U.S. agreement on all the NTGPR principles discussed here, China’s policy objectives with the U.S. are clearly derivative. To begin, Beijing seeks treatment as a peer great power through the elimination of “discriminatory” restrictions on U.S. technology exports, and U.S. respect for Chinese sovereignty by refraining from statements, policies, or demands regarding Chinese internal rule of law, human rights, or religious freedoms (Xinhua, June 10, 2013).

However, security issues are the greatest hurdle for Sino-U.S. NTGPR. In the near-term, Beijing seeks progress on the military confidence-building measures (notification of major military activities and standards of behavior for maritime safety) proposed to Washington, along with the elimination of what it views as “discriminatory” restrictions on broadened security exchanges. China also seeks to leverage U.S. influence over what China now calls “third parties” in sovereignty disputes in the East and South China Seas (CICIR, February 24).

But long-term, Beijing expects U.S. recognition of a privileged Chinese sphere in Asia and assurance that Washington will not intervene in the region—politically or militarily—contrary to China’s interests (People’s Daily, April 15, 2013). This requires U.S. concession on the “three obstacles” and dissolution of alliances that Beijing feels threaten China. Most importantly, this involves U.S. deference to Chinese security interests and sovereignty claims over the promotion of customary international law along China’s maritime periphery.

Last, Beijing’s idea of multipolarity could require U.S. acquiescence to more than a simple diffusion of global power to other “poles” in a multipolar system. Instead it could lead to increased rivalry and greater instability as other “poles” attempt to organize parts of the global architecture exclusively around themselves as China is already doing with the BRICS and SCO through the promotion of “New Type International Relations” (“Out with the New, In with the Old,” China Brief, April 25, 2013).

Conclusion

NTGPR is a well-developed, coherent outgrowth of Chinese foreign policy meant to stabilize great power relations and establish a “new international order” to shape U.S. behavior. While the both Washington and Beijing acknowledge the need to avoid conflict, there are significant difficulties regarding the principles framing NTGPR. Despite consensus on broadened areas of cooperation, security is still paramount in international relations, and is the issue where U.S. and Chinese interests are at significant odds.

For Beijing, rhetorical adoption of NTGPR limits Washington’s options, and so outright U.S. rejection now could cause deepening mistrust and a sharp downturn in relations due to unmet Chinese expectations. As Washington holds its policy line, Beijing’s frustration will grow, and it will increasingly accuse the U.S. of violating the “consensus” established at Sunnylands.

Provide an alternative. Henry Kissinger recently reminded us that “the test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins,” and so the U.S. must articulate its own vision for the evolving international order, one that is acceptable to both countries (Washington Post, March 5). As global power becomes more diffuse, Washington can no longer afford to be portrayed by Beijing as acting outside the international system it created and enforced in the decades since WWII. Instead, the U.S. should place the full weight of its authority in support of the rules and institutions Washington itself put into place to help the liberal order adapt peacefully to changes in the international system. But it must start with directly engaging China regarding the principles on which Washington envisions building the foundation of a New Type Great Power Relationship with Beijing.

Notes:

1. “New Type” is sometimes translated in English as “New Model,” and “Great Power” is sometimes translated as “Big Power” or “Major Power,” but the Chinese is consistent (xinxing daguo guanxi).

2. Those obstacles were Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia, and Soviet troops in Mongolia.

3. Three of four points proposed by Xi at Sunnylands resemble the “four-point proposal” raised by Hu Jintao with Dmitry Medvedev in 2008 and are clearly derivative from the same core principles (Xinhua, June 10, 2013; May 23, 2008).