Central Asia Ready to Follow China’s Lead despite Russian Ties

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 14 Issue: 71

By:

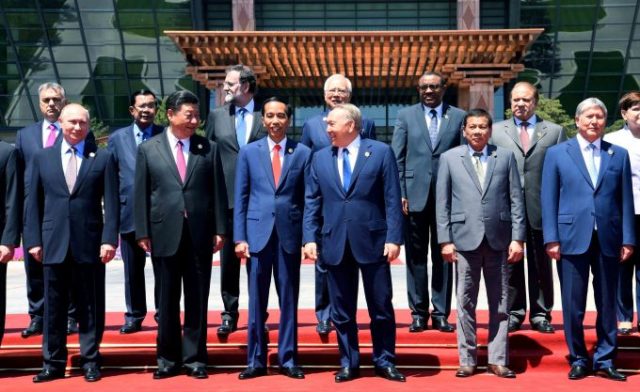

China hosted a major international gathering on May 14 and 15. Over a thousand delegates from 110 countries, including 29 world leaders, flocked to Beijing to attend the so-called One Belt, One Road Summit. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was first proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013. It has since grown into an ambitious transcontinental project aimed at asserting China’s new formative role in Eurasian affairs. In a bid to demonstrate the seriousness of his country’s foreign commitments, Xi kicked off the event by pledging $124 billion in a combination of aid, loans and investments. The Chinese government-owned media was careful to stress the high level of interest toward the BRI by noting the presence of the heads of the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a handful of presidents and prime ministers from the European Union, and President Vladimir Putin of Russia. The latter spoke alongside his fellow heads of state of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, who collectively represented Central Asia (Gazeta.ru, Akorda.kz, May 15; Gazeta.uz, Tazabek.kg, May 14).

Interestingly, the media coverage of the Beijing summit in the Central Asian region was unanimously positive; whereas in previous years China usually received both praise and criticism. Kazakhstani President Nursultan Nazarbayev, currently the longest-serving leader among his peers, oversaw the signing of an agreement whereby Kazakh Railways relinquished a 49 percent stake in the Khorgos transport hub on the Kazakhstani-Chinese border. What might have earlier caused second thoughts about the status of such a strategic transport facility, literally allowing Kazakhstan to control the flow of land-based trade between China and Europe, almost passed unnoticed. Last year’s protests over proposed land reform in Kazakhstan, which were partly driven by the fear of mass migration from China, therefore seem to be a dim recollection of the past (Kursiv.kz, May 15; Liter.kz, May 14; see EDM, May 16, 2016).

Caught in the midst of an unprecedented economic downturn, Kazakhstan more than ever needs Chinese investments. Meanwhile, the Chinese government has been attentive to the necessity of mitigating fears about presumed westward expansionism at the expense of local sovereignties. The same pragmatic approach has been the hallmark of Beijing’s relations with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Kyrgyzstani President Almazbek Atambayev actively talked up the “Digital Silk Road” of Eurasia and mused about his country’s potential role as a key logistics hub for massive companies like the Chinese online store Alibaba, which deliver their products to EU customers. His comments about a bilateral agreement to relocate production from China to Kyrgyzstan was met with particular optimism in the domestic media. Both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which, for both economic and geopolitical reasons, has failed so far to deliver on a solemn promise to spur growth, social mobility, and shared prosperity (Kabar.kg, Gezitter.org, May 18; Klop.kz, May 16).

Yet, the warmest welcome was reserved by the Chinese side to Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyaev whose five-day visit to Beijing was his first official trip outside of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). He brought home new business worth $20 billion, including a three-year natural gas supply contract and an agreement to build a synthetic fuel plant in Uzbekistan entirely funded with Chinese loans. According to Mirziyaev, Tashkent views the BRI as a means to reach the remote markets of the Persian Gulf and South Asia, namely through a potential extension of the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan rail link to Afghanistan and further south. The Uzbekistani media hailed “strategic partnership and cooperation” between the two countries and extensively reported on their president’s promise to nearly double bilateral trade to $10 billion in the near future (Gazeta.uz, May 13; Uza.uz, Uznews.uz, May 12; Uzdaily.uz, May 11).

In keeping with the same logic as in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia’s most populous country needs significant investments to modernize the economy after years of neglect in a context of partial isolation under the late Islam Karimov administration. FDI is equally needed by Uzbekistan’s neighbors Turkmenistan and Tajikistan. The Tajikistani government was represented in Beijing by its economy minister and the head of the state customs committee, whereas Ashgabat was not represented at all. Nevertheless, Turkmenistan remains the biggest supplier of piped natural gas to China and heavily relies on Chinese loans for large-scale infrastructure projects. The local media entirely ignored the BRI summit in Beijing, but wrote extensively about the visit of a Chinese parliamentary delegation to Turkmenistan a week later. A similar delegation was visiting Dushanbe just as Tajikistani officials in Beijing declared that bilateral trade might reach $3 billion by 2020 (Tdh.gov.tm, May 22; Avesta.tj, May 16; News.tj, Sputnik-tj.com, May 15).

Despite Vladimir Putin’s public praise of the BRI and its expected implications for Eurasian trade and development, Russia seemingly cannot help but be worried by China’s growing influence in what it still sees as its own backyard and a zone of exclusive domination. The Russian daily Nezavisimaya Gazeta, a prominent pro-government mouthpiece, published an article on May 15 titled “A Financial Noose Being Fastened Around Bishkek’s Neck.” The piece mildly criticized Kyrgyzstan’s expanding debt burden vis-à-vis China at a time when its critical railroad project, in the works for a decade, has still not been implemented. Moscow obviously fears that Beijing, with its enormous economic resources to push the BRI, will simply eclipse or even absorb the EEU, thus making Russia a client of China’s generous aid. Yet, the real concern goes much further. The BRI, however vague now, is already living proof of expanding Chinese soft power. In contrast, Russia’s intervention in Ukraine and its deep rift with the West over Syria and other issues have alienated many former allies in Central Asia.