How Lithuania’s Ham Radio Operators Outfoxed the Soviets in 1991

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 123

By:

Dictatorial regimes of all kinds have always sought to control communications, especially between those in their own countries and the outside world. With the Internet, their ability to do so has been much reduced; but it is important to remember that, even before the World Wide Web, their control was never quite as complete as many now think. In the struggle between those seeking freedom and those seeking to suppress it, the former have often been able to find ways to outfox the latter.

One of the most remarkable, if least known of these efforts, was the creation by ham radio operators in Lithuania of a news bridge to the United States and the rest of the world in the dark days of late 1990 and early 1991, when Mikheil Gorbachev’s regime was doing everything it could to block the recovery of Lithuanian independence. At a time when the Soviet authorities blocked telephone calls and when there was no permanent diplomatic presence in Vilnius, a group of a dozen Lithuanian ham radio enthusiasts ensured that the US and other Western countries received real time information about what was going on. Had they not done so, Western governments would not have been able to keep up, Moscow would have won an undeserved victory, and Lithuania’s march to freedom almost certainly would have been more difficult.

Historically, dictatorships have tended to hold an ambivalent view of amateur radio operators. On the one hand, they dislike the fact that such people can connect with their fellow enthusiasts abroad. But on the other, they see ham radio as potentially useful both in terms of ensuring communication within the country when natural disasters disrupt other forms of contact and as an advertisement of their supposed liberality (Eham.net, April 26, 2009; Archive.org, June 1965).

Lithuania has a long history of ham radio, both under the Soviet occupation and since that time (Lrmd.lt, accessed July 8). And Lithuania’s hams had a secret weapon that Moscow failed to count on: a large group of amateur radio enthusiasts in the Lithuanian diaspora in the United States that was ready to work with them and pass on the information they supplied to US officials. The KGB monitored their contacts, but for most of the Soviet period, the ham radio operators avoided the kind of political conversations that might have resulted in this bridge being shut down.

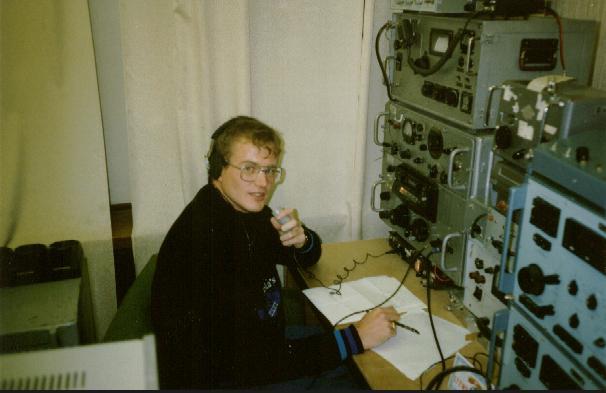

However, when Soviet forces launched their murderous attacks on Lithuanian demonstrators at the Vilnius TV tower, twelve Lithuanian hams became the voice of free Lithuania to the outside world. Rytis Žumbakis, Tadas Vyšniauskas, Arvydas Bilinkevičius, Virgis Zalensas, Rita Dapkus, Vilius Vašeikis, Viktoras Peteraitis, Valentinas Mackevičius, Alfredas Turauskas, Gintautas Gaidamavičius, Remigijus Lašinis, and Jonas Baniūnas set up ham operations at the television tower and in the parliament building with the respective call signs of LY2WR and LY2WR/A. A video showing them at work survives. It is available on YouTube (video posted on April 11, 2011).

Initially, these Lithuanian ham radio operators broadcast almost constantly to Lithuanians in the US and elsewhere. But after a few days, they became more systematic, issuing three main news reports each day, otherwise breaking radio silence only if there was a serious development. In the United States, Lithuanian hams took down their broadcasts in Boston in the early morning, in Chicago midday, and in San Francisco in the late afternoon, east coast time. Their efforts were coordinated by Rimas Pauliukonis, who lived in New Hampshire but worked in Boston. He was assisted by Vidas Bysniauskas of Detroit.

The Lithuanian-American ham radio operators recorded what their partners in Vilniius—and other Lithuanian cities as well—were reporting and gave it to Asta Banionis of the Lithuanian American Community’s Washington office, who passed it on to US government officials, including this author, who at the time worked as the State Department’s desk officer for Lithuania. Whenever Banionis’s calls came in that there was news from LY2WR and LY2WR/A, this author always felt the frisson that many feel at the end of the movie Air Force One, when the pilot of the rescue plane announces that his aircraft has had to change its call sign from its ordinary one to that of a plane carrying the President of the United States

Of those who were most immediately involved in this effort, all but Žumbakis remain alive. Their heroic efforts deserve to be remembered as a model of a remarkable way in which those struggling for their freedom can find ways around oppression. Happily, a generation after these events, Lithuania no longer has to rely on this unique channel of communication; and equally happily, the twelve brave Lithuanian hams are now to be memorialized with a plaque at the Vilnius television center. And a copy of that plague will be displayed in the Lithuanian embassy in Washington, DC.